Virginia is one of our “go-to” destinations — meaning it is within driving-range of home base for those shorter adventure trips and has public lands open to motorized recreation. Heading south it is the first state where we can really begin to feel the freedom of the wilderness and experience the “big country” sensations. We have two favorite north-south options here (coastal or mountains), and very often when doing a long trip, we make a loop and take one route south and the other one north on the return. There are also a number of official scenic byways to explore around the state (we incorporate a few of them into our route, too).

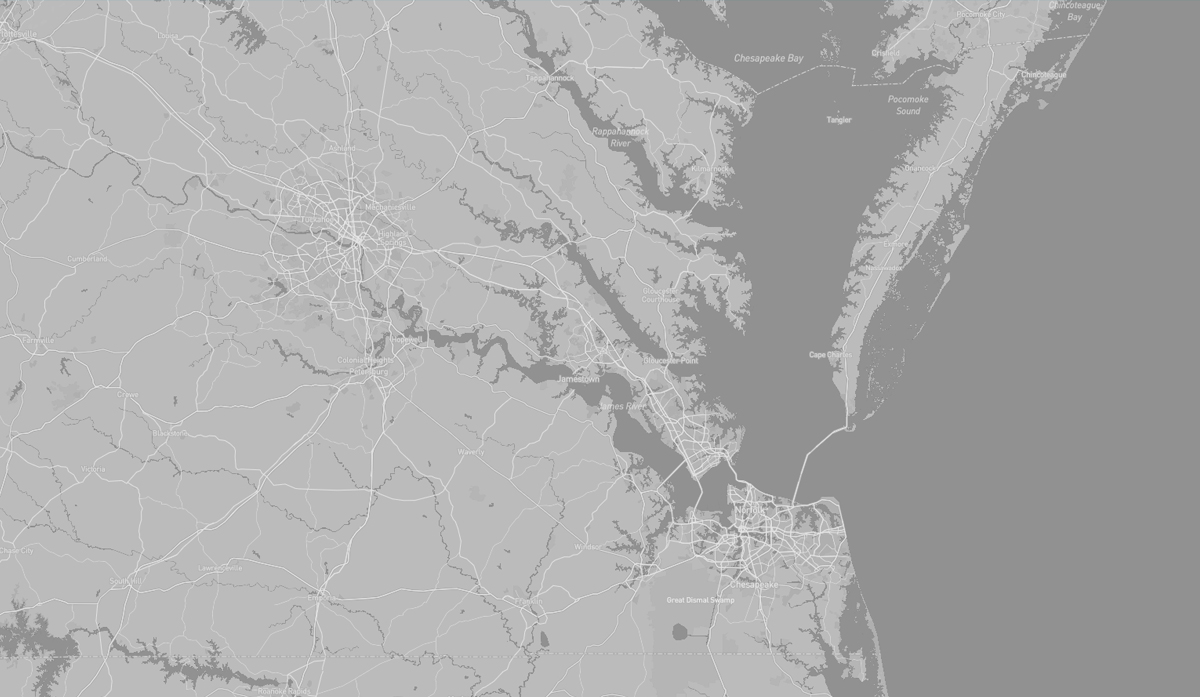

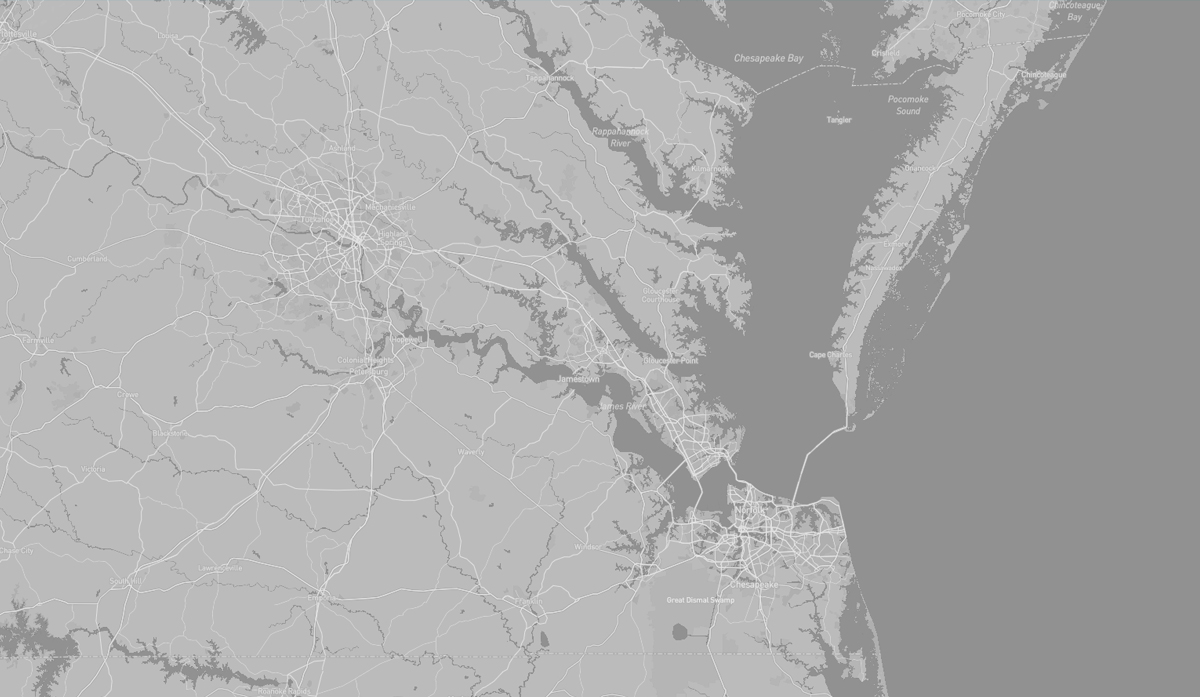

Overview: Located midway between New York and Florida, Virginia is the gateway to the South. The state is a combination of major metropolitan areas and their suburbs complemented by large rural regions and plenty of public lands to explore. The variety of landscapes lend themselves to different types of outdoor recreation depending on the region. Western Virginia is mountainous, covered by the Allegheny and Blue Ridge mountains with the great Shenandoah Valley falling between the ranges. The central piedmont region, with its rolling hills, flattens out into the sandy coastal plain toward the Atlantic Ocean.

Roughly 16.2% of the state is protected public lands of one sort or another. There are thirty National Park Service units in the state, such as Great Falls Park and the Appalachian Trail, and one National Park, Shenandoah. The U.S. Forest Service administers the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, which cover more than 1.6 million acres within Virginia’s mountains, and continue into West Virginia and Kentucky. The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge also extends into North Carolina, as does the Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which marks the beginning of the Outer Banks. State agencies control about one-third of protected land in the state, with forty Virginia state parks, 26 State Forests, 44 Wildlife Management Areas and 65 Natural Area Preserves.

TOPOGRAPHY: Eastern Virginia is part of the Atlantic Plain, with the Middle Peninsula forming the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The state’s central region lies mostly within the Piedmont, with the Blue Ridge Mountains crossing the western and southwestern parts of the state.

The Chesapeake Bay separates the contiguous portion of the state from the two-county peninsula of Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Many of Virginia’s rivers flow into the Bay, including the Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James, which create three distinct peninsulas in the bay, traditionally referred to as “necks.” The Piedmont is a series of sedimentary and igneous rock-based foothills east of the mountains known for its heavy clay soil. The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the Appalachian Mountains with the highest points in the state–the tallest being Mount Rogers at 5,729 feet. The Ridge-and-Valley region is west of the mountains and includes the Massanutten Mountain ridge and the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. The Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains are in the southwest corner of Virginia, south of the Allegheny Plateau. In this region, rivers flow northwest, with a dendritic drainage system, into the Ohio River basin. Coal mining takes place in the three mountainous regions at 45 distinct coal beds.

Forests cover 62% of Virginia, the majority are “hardwood forest” with a little less than a quarter being pine. The loblolly and shortleaf pine are primarily in central and eastern Virginia. Oak and hickory are most common in the western and mountainous regions. And bald cypress wetland forests can be found in the Great Dismal and Nottoway swamps.

Virginia has more than 4,000 limestone caves, ten of which are open for tourism, including the popular Luray Caverns and Skyline Caverns. Virginia’s iconic Natural Bridge is also the remaining roof of a collapsed limestone cave.

HISTORY: Nomadic hunters are estimated to have arrived in Virginia around 17,000 years ago. During the late Woodland period (500–1000 CE), tribes coalesced, and farming, first of corn and squash, began, with beans and tobacco arriving from the southwest and Mexico by the end of the period. Palisaded towns began to be built around 1200, and the native population in the current boundaries of Virginia reached around 50,000 in the 1500s. Large groups in the area at that time included the Algonquian in the Tidewater region, the Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway and Meherrin to the north and south, and the Tutelo, who spoke Siouan, to the west. During the 1570s thirty or so Virginia Algonquian-speaking tribes consolidated under Chief Powhatan, who controlled more than 150 settlements that had total population of around 15,000 by 1607 when the first European settlement was established at Jamestown.

In the century that followed three-fourths of the native population died from smallpox and other Old World diseases. Today there are seven federally recognized tribes in Virginia: the Pamunkey Indian Tribe, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond and Monacan. Only two of them, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi, have retained reservation lands based on 17th-century treaties made with the English colonists.

Virginia initially developed it’s economy based on the tobacco plantation system and enslaved Africans were first sold in Virginia in 1619. Between 1790 and 1860, the number of slaves in Virginia rose from around 290 thousand to over 490 thousand, roughly one-third of the state population during that time. But years of monoculture tobacco farming began to degrade Virginia’s agricultural productivity. Meanwhile a boom in cotton production across the South increased the demand for slave-labor just as new federal laws prohibited the importation of additional slaves from abroad. In response Virginia plantations increasingly turned to exporting their slaves “down south.”

After the Civil War, Northern capitalists financed railroad expansion into the coal fields of West Virginia and Virginia to fuel industrialization. The Appalachian Plateau shifted from subsidence agriculture to a cash economy based on lumbering and mineral extraction. Company towns were constructed and new employees recruited to man the deep mines. Mining communities grew up and shut down, based on the boom and bust cycles of the international energy markets. Physically, Virginia’s coal country was literally reshaped by strip mining since the 1930’s, as sandstone, shale, and limestone was scraped away and dumped in nearby valleys. Today restrictions on pollution mitigate the effects, but the requirements to restoring mined areas to their approximate original contour do not apply if the entire mountaintop is removed.

Coastal Virginia continues along the Delmarva Peninsula and the chain of barrier islands, down to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay where an amazing feat of modern engineering, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel spans the bay for almost 20 miles to reconnect to the mainland near Norfolk and Virginia Beach. The wetlands of the Great Dismal Swamp stretch out across the border with North Carolina, and continuing on the coastal route, and the barrier islands, we enter the start of the “Outer Banks.”

The Virginia Barrier Islands are a continuous chain of long, thin, low-lying, sand and scrub islands separated from one another by narrow inlets and from the mainland by a series of shallow marshy bays along the entire coast of the Virginia end of the Delmarva Peninsula, terminating to the south at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. As the first line of defense during storms that threaten coastal communities, these islands are very important for reducing the devastating effects of wind and waves and for absorbing storm energy. They are also an important ecological region providing a marine habitat that supports commercial fishing, as well as birds, sea turtles and other wildlife species.

A barrier island consists of four different zones: salt marsh, barrier flat, dunes and beach.

The “Salt marsh” is a low-lying area on the sound-side of a barrier island that is stabilized by cord grasses and flooded by daily tidal activity.

The “barrier flat” is formed from sediment pushed through the dunes by storms and stabilized by grasses.

The “dunes” consist of sand that has been carried and deposited by winds. Dunes are naturally stabilized by plants and sometimes artificially by fencing.

The “beach” is the ocean side of the island with sand deposited by wave action.

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife

observation, Marshland,

Beach, Hiking, Beach

Driving, Wild ponies, Historic

structures, Wildlife Drive

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife

observation, Hiking, Historic structures

HIGHLIGHTS: Bridge that

turns into a tunnel under

the water, then back up to

a bridge

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife

Observation, Swamp

landscape, Hiking,

Wildlife Drive

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife observation, Marshland, Beach, Hiking, Beach Driving, Wild ponies, Historic structures, Wildlife Drive

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, located on the southern end of 37-mile-long Assateague Island, within the boundaries of Assateague Island National Seashore, was established in 1943 to provide habitat for migratory birds. Chincoteague, managed jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Parks Service, is one of the most visited refuges in the United States. It includes more than 14,000 acres of sandy beaches, salt marshes, maritime forests and coastal bays connected via a series of small bridges and causeways.

Vehicle use on the beaches of the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is by permit only. The Over Sand Vehicle area is clearly marked, and the route via sand goes south for about 2.5 miles to the base of the “hook” and then for about 5 more miles around the to a fishing access point on the bay side beyond which you cannot drive. The drive on sand is generally easy for a properly equipped and aired down vehicle and there are no obstacles apart from pockets of softer sand here and there. Note that it IS CRITICAL to be aware of the high tide times and be off the beach well before it peaks because the incoming tide can trap a vehicle on the narrowest stretches of the beach route.

The refuge maintains several miles of hiking and biking trails. Hikers have 15 miles of trails to explore, and half of those are paved for bicycling and wheelchairs. The 3.2-mile, paved Wildlife Loop gives hikers and bikers access to Snow Goose Pool and Swan Cove. Vehicles are permitted on the loop between 3 p.m. and dusk. The waterways and ponds beside the road always hold a snowy egret, or the elegant great blue heron, or perhaps a flock of Canada geese. In addition to the Wildlife Loop, other hiking opportunities include the 1.6-mile Woodland Trail loop (walking and bicycling allowed) and the 0.25-mile (one-way) Lighthouse Trail to the photogenic Assateague Lighthouse. Built in the 1860s, this tower lighthouse with its alternating red and white rings still operates with a flashing light. The pine forests of the refuge hold white-tailed deer and the much smaller Sika deer. Sikas, which are actually an Oriental species of elk, were released on Assateague Island in the 1920s.

Wild ponies also roam the island and are a common sight as they graze the salt marshes. Popular legend tells of ponies that escaped a shipwrecked Spanish galleon and swam ashore, however most historians believe the ponies are descendants from animals belonging to settlers who used the island for grazing livestock in the 17th Century to avoid fencing regulations and taxation. Even though no one is certain how the ponies got to the island, their descendants still live there today.

The island is accessible from the mainland from both the Maryland end and the Virginia end, but there are no roads on the island that connect the north and south ends (in fact, a fence on the state line keeps even the wild ponies that roam the island from mixing).

CHINCOTEAGUE NWR HIGHLIGHTS FROM OUR ROADBOOK: WAYPOINT–Chincoteague Island NWR | FIELD NOTES—Maryland to Virginia

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife observation, Hiking, Historic structures

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife observation, Hiking, Historic structures

The Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge is at the southern end of the Eastern Shore near the tip of the Delmarva Peninsula. Much of the land that makes up this Refuge was previously part of Fort John Custis/Cape Charles Air Force Station, a base used by the United States Army 1941–1948 and the United States Air Force from 1948 until 1981. Gun batteries remain from the Army period and several buildings remain from the Air Force period. A 16″/50 caliber Mark 7 gun and a projectile from an Iowa-class battleship have been placed at Battery Winslow.

A fun short (.5-mile) hike along the Wildlife Trail is a great way to get an introduction to the Refuge. This easy loop trail takes visitors through mixed hardwoods, past an old cemetery, and out to the saltmarsh overlook. From there it continues to the top of a WWII-era bunker for a panoramic view of refuge marshes, barrier islands, bays, inlets, and the Atlantic Ocean.

HIGHLIGHTS: Bridge that turns into a tunnel under the water, then back up to a bridge

Taking the U.S. Route 13 down the Delmarva peninsula is a beautiful drive that leads to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel. An incredible engineering feat, the 20-mile long “CBBT” allows us to drive straight across the bay, over and under the open waters where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean.

The drive is something to experience, as you have the impression of actually driving ON the water, and then descending down into it to get to the tunnel sections. It is a journey of elevation changes, with two high-level bridges combined with a series of low-level trestles interrupted by two approximately one-mile-long tunnels that go beneath Thimble Shoals and Chesapeake navigation channels. There are manmade islands, each approximately 5.25 acres in size, at each end of the two tunnels, and between North Channel and Fisherman Inlet, the route crosses the water at-grade over Fisherman Island. It takes about 20-30 minutes to get to the other side and there are a couple of scenic turnoffs for photos.

HIGHLIGHTS: Wildlife Observation, Swamp landscape, Hiking, Wildlife Drive

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge contains some of the most important wildlife habitat in the mid-Atlantic region. At near 113,000 acres, the refuge is the largest intact remnant of a vast swamp that once covered more than one million acres. Outside the boundaries of the national wildlife refuge, the state of North Carolina has preserved and protected additional portions of the swamp through the establishment of the Dismal Swamp State Park, protecting an additional 22 square miles of forested wetland.

The Refuge has several hiking trails and the Lake Drummond Wildlife Drive, a self-guided 6-mile (one-way) gravel road that features three boardwalks to stop at along the way. The route starts at the Railroad Ditch trailhead and terminates at the lake with access to boating, fishing, and wildlife observation opportunities.

The Great Dismal Swamp itself has an interesting history. Archaeological evidence suggests varying cultures of humans have inhabited the swamp for 13,000 years. The Powhatan empire extended to the northern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp around the time of the settling of Jamestown, displacing the Chesapeake tribe residing there before. In 1650, Algonquian-speaking Native Americans lived in the swamp.

In 1728, William Byrd II, while leading a land survey to establish a boundary between the Virginia and North Carolina colonies, made many observations of the swamp and he is credited with naming it the Dismal Swamp. At that time, the swamp was estimated to cover around 2,000 square miles. Settlers did not appreciate the ecological importance of wetlands. In 1763, George Washington visited the area, and he and others founded the Dismal Swamp Company in a venture to drain the swamp and clear it for settlement. The company later turned to the more profitable goal of timber harvesting. The Dismal Swamp Canal was authorized by Virginia in 1787 and by North Carolina in 1790. Construction began in 1793 and was completed in 1805. The canal, as well as a railroad constructed through part of the swamp in 1830, enabled the harvest of timber.

At the same time, the swamp became a place of refuge for peoples looking to escape the colonial American system. Native American communities fled to the Swamp for refuge from the expanding colonial frontier. There was also multiple populations of Africans and African Americans taking refuge in the Swamp, many of them fleeing slavery — they became known as the Great Dismal Swamp maroons. The origin of the word maroon is uncertain, but it is widely believed that the word comes from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “wild” or “untamed”. Maroons, self-liberated Africans in isolated or hidden settlements, existed in all the Southern states, and swamp-based maroon communities could be found throughout the Deep South, in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina. They were able to find shelter, community and society in the swamp that wasn’t readily available outside. Most of those in the Great Dismal Swamp settled on mesic islands, the high and dry parts of the swamp. Inhabitants included people who had purchased their freedom as well as those who had escaped.

Other people used the swamp as a route on the Underground Railroad as they made their way further north. Harriet Beecher Stowe told the maroon people’s story in her 1856 novel Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. Excavations reveal island communities existing until the Civil War. Charlie, a maroon who worked illegally in a lumber camp in the swamp, later recalled that there were whole families of maroons living in the Dismal Swamp, some of whom had never seen a white man. The Great Dismal Swamp maroons numbered in the thousands by the year 1860. The most significant research on the settlements began in 2002 with a project by Dan Sayers of American University. Results of a study published in 2007, “The Political Economy of Exile in the Great Dismal Swamp”, say that thousands of people lived there between 1630 and 1865, Native Americans, maroons and enslaved laborers on the canal. It is believed to have been one of the largest maroon colonies in the United States.

Fear of slave unrest and fugitive slaves living in the maroon colony caused concern amongst local whites. A militia with dogs went into the swamp in 1823 in an attempt to remove the maroons and destroy their community, but most people escaped. In 1847, North Carolina passed a law specifically aimed at apprehending the maroons in the swamp. However, unlike other maroon communities, where local militias often captured the residents and destroyed their homes, those in the Great Dismal Swamp mostly avoided capture or the discovery of their homes. During the American Civil War, the United States Colored Troops entered the swamp to liberate the people there, many of whom then joined the Union Army. Most of the maroons who remained in the swamp left after the Civil War.

In 1929, the United States Government bought the Dismal Swamp Canal and began to improve it. The canal is now the oldest operating artificial waterway in the country. Like the Albemarle and Chesapeake canals, it is part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1973 when the Union Camp Corporation of Franklin, Virginia, donated 49,100 acres of land after centuries of logging and other human activities devastated the swamp’s ecosystems.

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, located on the southern end of 37-mile-long Assateague Island, within the boundaries of Assateague Island National Seashore, was established in 1943 to provide habitat for migratory birds. Chincoteague, managed jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Parks Service, is one of the most visited refuges in the United States. It includes more than 14,000 acres of sandy beaches, salt marshes, maritime forests and coastal bays connected via a series of small bridges and causeways.

Vehicle use on the beaches of the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is by permit only. The Over Sand Vehicle area is clearly marked, and the route via sand goes south for about 2.5 miles to the base of the “hook” and then for about 5 more miles around the to a fishing access point on the bay side beyond which you cannot drive. The drive on sand is generally easy for a properly equipped and aired down vehicle and there are no obstacles apart from pockets of softer sand here and there. Note that it IS CRITICAL to be aware of the high tide times and be off the beach well before it peaks because the incoming tide can trap a vehicle on the narrowest stretches of the beach route.

The refuge maintains several miles of hiking and biking trails. Hikers have 15 miles of trails to explore, and half of those are paved for bicycling and wheelchairs. The 3.2-mile, paved Wildlife Loop gives hikers and bikers access to Snow Goose Pool and Swan Cove. Vehicles are permitted on the loop between 3 p.m. and dusk. The waterways and ponds beside the road always hold a snowy egret, or the elegant great blue heron, or perhaps a flock of Canada geese. In addition to the Wildlife Loop, other hiking opportunities include the 1.6-mile Woodland Trail loop (walking and bicycling allowed) and the 0.25-mile (one-way) Lighthouse Trail to the photogenic Assateague Lighthouse. Built in the 1860s, this tower lighthouse with its alternating red and white rings still operates with a flashing light. The pine forests of the refuge hold white-tailed deer and the much smaller Sika deer. Sikas, which are actually an Oriental species of elk, were released on Assateague Island in the 1920s.

Wild ponies also roam the island and are a common sight as they graze the salt marshes. Popular legend tells of ponies that escaped a shipwrecked Spanish galleon and swam ashore, however most historians believe the ponies are descendants from animals belonging to settlers who used the island for grazing livestock in the 17th Century to avoid fencing regulations and taxation. Even though no one is certain how the ponies got to the island, their descendants still live there today.

The island is accessible from the mainland from both the Maryland end and the Virginia end, but there are no roads on the island that connect the north and south ends (in fact, a fence on the state line keeps even the wild ponies that roam the island from mixing).

CHINCOTEAGUE NWR HIGHLIGHTS FROM OUR ROADBOOK: WAYPOINT–Chincoteague Island NWR | FIELD NOTES—Maryland to Virginia

The Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge is at the southern end of the Eastern Shore near the tip of the Delmarva Peninsula. Much of the land that makes up this Refuge was previously part of Fort John Custis/Cape Charles Air Force Station, a base used by the United States Army 1941–1948 and the United States Air Force from 1948 until 1981. Gun batteries remain from the Army period and several buildings remain from the Air Force period. A 16″/50 caliber Mark 7 gun and a projectile from an Iowa-class battleship have been placed at Battery Winslow.

A fun short (.5-mile) hike along the Wildlife Trail is a great way to get an introduction to the Refuge. This easy loop trail takes visitors through mixed hardwoods, past an old cemetery, and out to the saltmarsh overlook. From there it continues to the top of a WWII-era bunker for a panoramic view of refuge marshes, barrier islands, bays, inlets, and the Atlantic Ocean.

Taking the U.S. Route 13 down the Delmarva peninsula is a beautiful drive that leads to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel. An incredible engineering feat, the 20-mile long “CBBT” allows us to drive straight across the bay, over and under the open waters where the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean.

The drive is something to experience, as you have the impression of actually driving ON the water, and then descending down into it to get to the tunnel sections. It is a journey of elevation changes, with two high-level bridges combined with a series of low-level trestles interrupted by two approximately one-mile-long tunnels that go beneath Thimble Shoals and Chesapeake navigation channels. There are manmade islands, each approximately 5.25 acres in size, at each end of the two tunnels, and between North Channel and Fisherman Inlet, the route crosses the water at-grade over Fisherman Island. It takes about 20-30 minutes to get to the other side and there are a couple of scenic turnoffs for photos.

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge contains some of the most important wildlife habitat in the mid-Atlantic region. At near 113,000 acres, the refuge is the largest intact remnant of a vast swamp that once covered more than one million acres. Outside the boundaries of the national wildlife refuge, the state of North Carolina has preserved and protected additional portions of the swamp through the establishment of the Dismal Swamp State Park, protecting an additional 22 square miles of forested wetland.

The Refuge has several hiking trails and the Lake Drummond Wildlife Drive, a self-guided 6-mile (one-way) gravel road that features three boardwalks to stop at along the way. The route starts at the Railroad Ditch trailhead and terminates at the lake with access to boating, fishing, and wildlife observation opportunities.

The Great Dismal Swamp itself has an interesting history. Archaeological evidence suggests varying cultures of humans have inhabited the swamp for 13,000 years. The Powhatan empire extended to the northern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp around the time of the settling of Jamestown, displacing the Chesapeake tribe residing there before. In 1650, Algonquian-speaking Native Americans lived in the swamp.

In 1728, William Byrd II, while leading a land survey to establish a boundary between the Virginia and North Carolina colonies, made many observations of the swamp and he is credited with naming it the Dismal Swamp. At that time, the swamp was estimated to cover around 2,000 square miles. Settlers did not appreciate the ecological importance of wetlands. In 1763, George Washington visited the area, and he and others founded the Dismal Swamp Company in a venture to drain the swamp and clear it for settlement. The company later turned to the more profitable goal of timber harvesting. The Dismal Swamp Canal was authorized by Virginia in 1787 and by North Carolina in 1790. Construction began in 1793 and was completed in 1805. The canal, as well as a railroad constructed through part of the swamp in 1830, enabled the harvest of timber.

At the same time, the swamp became a place of refuge for peoples looking to escape the colonial American system. Native American communities fled to the Swamp for refuge from the expanding colonial frontier. There was also multiple populations of Africans and African Americans taking refuge in the Swamp, many of them fleeing slavery — they became known as the Great Dismal Swamp maroons. The origin of the word maroon is uncertain, but it is widely believed that the word comes from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “wild” or “untamed”. Maroons, self-liberated Africans in isolated or hidden settlements, existed in all the Southern states, and swamp-based maroon communities could be found throughout the Deep South, in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina. They were able to find shelter, community and society in the swamp that wasn’t readily available outside. Most of those in the Great Dismal Swamp settled on mesic islands, the high and dry parts of the swamp. Inhabitants included people who had purchased their freedom as well as those who had escaped.

Other people used the swamp as a route on the Underground Railroad as they made their way further north. Harriet Beecher Stowe told the maroon people’s story in her 1856 novel Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp. Excavations reveal island communities existing until the Civil War. Charlie, a maroon who worked illegally in a lumber camp in the swamp, later recalled that there were whole families of maroons living in the Dismal Swamp, some of whom had never seen a white man. The Great Dismal Swamp maroons numbered in the thousands by the year 1860. The most significant research on the settlements began in 2002 with a project by Dan Sayers of American University. Results of a study published in 2007, “The Political Economy of Exile in the Great Dismal Swamp”, say that thousands of people lived there between 1630 and 1865, Native Americans, maroons and enslaved laborers on the canal. It is believed to have been one of the largest maroon colonies in the United States.

Fear of slave unrest and fugitive slaves living in the maroon colony caused concern amongst local whites. A militia with dogs went into the swamp in 1823 in an attempt to remove the maroons and destroy their community, but most people escaped. In 1847, North Carolina passed a law specifically aimed at apprehending the maroons in the swamp. However, unlike other maroon communities, where local militias often captured the residents and destroyed their homes, those in the Great Dismal Swamp mostly avoided capture or the discovery of their homes. During the American Civil War, the United States Colored Troops entered the swamp to liberate the people there, many of whom then joined the Union Army. Most of the maroons who remained in the swamp left after the Civil War.

In 1929, the United States Government bought the Dismal Swamp Canal and began to improve it. The canal is now the oldest operating artificial waterway in the country. Like the Albemarle and Chesapeake canals, it is part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1973 when the Union Camp Corporation of Franklin, Virginia, donated 49,100 acres of land after centuries of logging and other human activities devastated the swamp’s ecosystems.

Beach driving at Chincoteague NWR with permit. Street legal vehicles only.

Camping at campgrounds only (no dispersed camping)

Gas, food and water are all easily accessible.

The Potomac River brings together a variety of cultures throughout the watershed from the coal miners of upstream West Virginia to the urban residents of the nation’s capital and, along the lower Potomac, the watermen of Virginia’s Northern Neck. We will be focusing our attention on the “Northern Neck” segment of the river which is far enough from the metro DC area to maintain a sense of wilderness. Steeped in history, it’s a region where generations of watermen continue to harvest Rockfish, Blue Crabs and the ever famous Virginia Oyster from the waters surround the peninsula. Family produce farms are still flourishing and it retains a rural sense of place.

The “Tidal” Potomac River is the 108-mile stretch running from below the Washington, DC – Montgomery County line, just downstream of the Little Falls of the Potomac River, to the Chesapeake Bay. The “Northern Neck” peninsula is only 20 miles across at its widest point and the terrain includes farms, forests, tidal wetlands, rivers, streams, and marshes. This area has more than 1,130 miles of shoreline. The Northern Neck can be divided into three different habitats: neckland, upland, and cliffs. The neckland is nearly level and borders most of the waterways extending into the lower portions of the upland. The dividing line between neckland and upland is mainly marked by a distinct slope or scarp that starts at an elevation of about 50 feet and rises to about 100 feet. Cliffs are found along the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers, with some of the steepest found in Westmoreland State Park.

When paddling on busy waterways like the Potomac River, it is important to be aware of larger, faster moving traffic. Here are a few tips for staying safe out there.

HIGHLIGHTS: Paddling,

Wildlife observation,

Historic sites

HIGHLIGHTS: Hiking,

Paddling, Interpretive

activities

HIGHLIGHTS: Hiking trails,

Historic ruins, Interpretive

activities

HIGHLIGHTS: Paddling, Wildlife observation, Historic sites

The Potomac National Heritage Trail follows the course of the river across three states and the nation’s capital. While it is possible to paddle the entire 355 miles, beginning at Jennings Randolph Lake and going all the way to the Chesapeake Bay, there are plenty of options for single or multi-day trips, too.

The creeks and protected shores of the Potomac are well suited for exploring in canoes and kayaks. The river itself is large and powerful, with frequent heavy traffic and strong currents. If you’re a novice or intermediate paddler, keep to shorter trips inside creeks like those at Point Lookout State Park and Dyke Marsh. Longer Potomac River trips should only be undertaken by experienced and physically fit sea kayakers familiar with the precautions needed to stay safe.

Within the Northern Neck of Virginia region spanning from Midway Island VA to Reedville VA the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail winds through miles of timberland, farms, and shoreline. The trail follows the route visited by Captain John Smith and his crew in the early 1600s.

Smith traveled nearly 3,000 miles on the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers, recording and mapping what he saw. Due largely to Smith’s descriptions, European settlement followed along these waterways.

Traveling these waters today, you can see how the landscape has changed — and where it has changed very little. You can see where history was made and where wildlife and native plants still thrive.

HIGHLIGHTS: Hiking, Paddling, Interpretive activities

Caledon State Park provides a retreat into nature and history for all who enter its gates. A National Natural Landmark known for its old growth forest Caldeon is summer home to one of the largest concentrations of American bald eagles on the East Coast.

The best way to catch a glimpse of the eagles is to hike down to the river in the morning, looking at the tree line along the beach and the sky above the river. Caledon’s best trails for eagle-sighting are Boyd’s Hole Trail and the Jones Pond Loop. If you are looking to catch a glimpse of an eagle’s nest, the Rookery Spur is the trail for you. December is a great time to view Bald Eagles pairing up, and summer is the best time to see the juveniles playing and trying out their wings for the first time as they learn to hunt and fish.

Caledon has a huge focus on interpretation, with lots of cool activities for visitors like Eagle Tours, Owl Prowls and Sunset Kayak Trips. Call the park for more information on these opportunities: 540-663-3861.

The only camping in the park is primitive paddle-in tent camping nestled along the shoreline of the Potomac River. The paddle-in campground is part of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail (it is also possible to hike-in, but it is a 3.5 mile walk from the parking area). The park has no drive-to sites.

Ten hiking and four multi-use trails take park visitors through environmentally sensitive marshlands and picturesque wooded areas of the park.

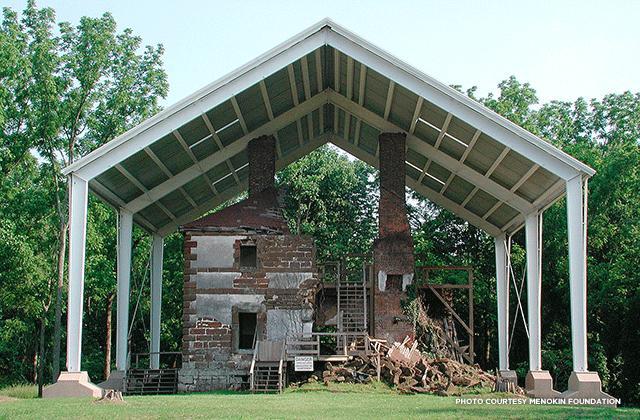

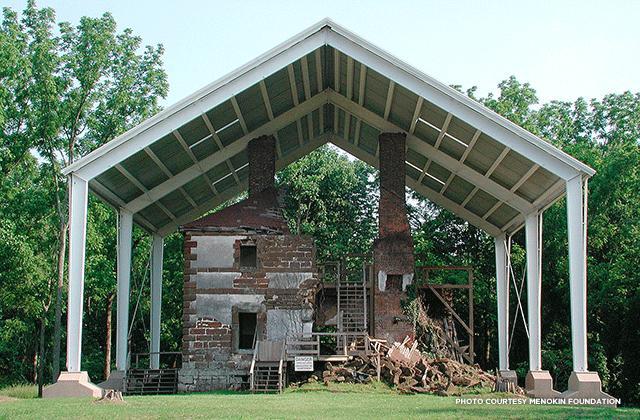

HIGHLIGHTS: Hiking trails, Historic ruins, Interpretive activities

Menokin was the home of Francis Lightfoot Lee — a signer of the Declaration of Independence — and is one of the best documented 18th century houses in the United States. The site’s 500 acres are an unspoiled, waterfront refuge featuring pristine bird habitats, remnants of the 18th-century agricultural landscape, and miles of woodland trails.

Water surrounds Menokin. The property itself contains a half-mile of shoreline on Cat Point Creek, an unspoiled tributary nine miles upstream from the Rappahannock River. Improvements to the historic road leading to the creek grants greater access to the water and Menokin Landing (the former wharf). The property features forest with woodland trails, fields, marshes, and shoreline. Of Menokin’s 500 acres, 325 are part of the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge. The land is in an Important Bird Area, a National Audubon Society designation, with a high concentration of bald eagles.

The plantation and house were established in 1769 on land once inhabited by the Rappahannock Tribe, who gave the site its name. During it’s time as an active plantation, the Menokin property had livestock and a fluctuating population of as many as 48 enslaved people. Remnants of that era include the former slave quarters sites and traces of tobacco rolling roads — where tobacco hogsheads were rolled down the slopes to the landing on Menokin Bay and loaded onto barges to be shipped to England. After the collapse of the plantation culture, Menokin continued as a working farm.

Visitors can explore the grounds independently or schedule a guided tour of the landscape and Menokin ruins for an interpretive experience. Menokin also offers seasonal kayak rentals through Rappahannock Outdoor Adventures.

The Potomac National Heritage Trail follows the course of the river across three states and the nation’s capital. While it is possible to paddle the entire 355 miles, beginning at Jennings Randolph Lake and going all the way to the Chesapeake Bay, there are plenty of options for single or multi-day trips, too.

The creeks and protected shores of the Potomac are well suited for exploring in canoes and kayaks. The river itself is large and powerful, with frequent heavy traffic and strong currents. If you’re a novice or intermediate paddler, keep to shorter trips inside creeks like those at Point Lookout State Park and Dyke Marsh. Longer Potomac River trips should only be undertaken by experienced and physically fit sea kayakers familiar with the precautions needed to stay safe.

Within the Northern Neck of Virginia region spanning from Midway Island VA to Reedville VA the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail winds through miles of timberland, farms, and shoreline. The trail follows the route visited by Captain John Smith and his crew in the early 1600s.

Smith traveled nearly 3,000 miles on the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers, recording and mapping what he saw. Due largely to Smith’s descriptions, European settlement followed along these waterways.

Traveling these waters today, you can see how the landscape has changed — and where it has changed very little. You can see where history was made and where wildlife and native plants still thrive.

Caledon State Park provides a retreat into nature and history for all who enter its gates. A National Natural Landmark known for its old growth forest Caldeon is summer home to one of the largest concentrations of American bald eagles on the East Coast.

The best way to catch a glimpse of the eagles is to hike down to the river in the morning, looking at the tree line along the beach and the sky above the river. Caledon’s best trails for eagle-sighting are Boyd’s Hole Trail and the Jones Pond Loop. If you are looking to catch a glimpse of an eagle’s nest, the Rookery Spur is the trail for you. December is a great time to view Bald Eagles pairing up, and summer is the best time to see the juveniles playing and trying out their wings for the first time as they learn to hunt and fish.

Caledon has a huge focus on interpretation, with lots of cool activities for visitors like Eagle Tours, Owl Prowls and Sunset Kayak Trips. Call the park for more information on these opportunities: 540-663-3861.

The only camping in the park is primitive paddle-in tent camping nestled along the shoreline of the Potomac River. The paddle-in campground is part of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail (it is also possible to hike-in, but it is a 3.5 mile walk from the parking area). The park has no drive-to sites.

Ten hiking and four multi-use trails take park visitors through environmentally sensitive marshlands and picturesque wooded areas of the park.

Menokin was the home of Francis Lightfoot Lee — a signer of the Declaration of Independence — and is one of the best documented 18th century houses in the United States. The site’s 500 acres are an unspoiled, waterfront refuge featuring pristine bird habitats, remnants of the 18th-century agricultural landscape, and miles of woodland trails.

Water surrounds Menokin. The property itself contains a half-mile of shoreline on Cat Point Creek, an unspoiled tributary nine miles upstream from the Rappahannock River. Improvements to the historic road leading to the creek grants greater access to the water and Menokin Landing (the former wharf). The property features forest with woodland trails, fields, marshes, and shoreline. Of Menokin’s 500 acres, 325 are part of the Rappahannock River Valley National Wildlife Refuge. The land is in an Important Bird Area, a National Audubon Society designation, with a high concentration of bald eagles.

The plantation and house were established in 1769 on land once inhabited by the Rappahannock Tribe, who gave the site its name. During it’s time as an active plantation, the Menokin property had livestock and a fluctuating population of as many as 48 enslaved people. Remnants of that era include the former slave quarters sites and traces of tobacco rolling roads — where tobacco hogsheads were rolled down the slopes to the landing on Menokin Bay and loaded onto barges to be shipped to England. After the collapse of the plantation culture, Menokin continued as a working farm.

Visitors can explore the grounds independently or schedule a guided tour of the landscape and Menokin ruins for an interpretive experience. Menokin also offers seasonal kayak rentals through Rappahannock Outdoor Adventures.

Paved roads only.

Camping at campgrounds only (no dispersed camping)

Gas, food and water are all easily accessible.

The western side of Virginia is framed by two parallel sets of mountains running roughly north-northwest to south-southwest with a large valley in between. It is an area of woodlands, mountains, caverns, rivers and lakes and much of it is open for exploration and outdoor recreation. The Blue Ridge Mountains are on the east and the Allegheny Mountains are on the west, the Shenandoah Valley sits between them. Roughly speaking, the Shenandoah Valley begins at the top of Virginia via I-81 and is approximately 140 miles long ending in Rockbridge County.

Two of the most popular scenic drives in America are located here — the Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park and the northern segment of the Blue Ridge Parkway (both are paved scenic highways, but definitely worth including in a road trip). These two “byways” actually can “connect” near the town of Afton to make one long north-south route.

Throughout the region there are hiking trails that range from an easy stroll in the woods to multi-day excursions (the Appalachian Trail winds through here). Dramatic underground caverns offer well-known and dramatic examples of underground passages, rooms, watercourses, formations, and other cave features that honeycomb much of the land below central and southern Appalachia. There are plenty of options for paddling and motorized recreation, too.

The Appalachian Mountains are the eastern counterpart to the Rocky Mountains in the west. They form a natural barrier between the eastern Coastal Plain and the vast Interior Lowlands of North America.

The Appalachians are among the oldest mountains in the world. They began forming about 270 million years ago, when the land masses that would become North America and Africa collided. The collision piled up masses of rock along the margin of North America to form the Appalachians.

The Appalachians were once as tall as the Rocky Mountains. Over millions of years, erosion from ice, wind, and water carved the mountains into their current shapes. Today, geologists estimate that they erode about two inches every 1,000 years.

Sometimes it seems hard to know which mountains are which. People seem to call the same set of mountains by different names and it can get confusing. There is actually a hierarchy of "mountain systems."

The Appalachian Mountains are technically the whole vast system of mountains that run for 2,000 miles from Canada, down through the eastern United States into Alabama. Within that range, there are "sub-ranges." The Blue Ridge Mountains are a subrange of the Appalachians that run from southern Pennsylvania down to northern Georgia, the Allegheny Mountains are a subrange of the Appalachians that run from southern Pennsylvania down through western Maryland, and the Great Smoky Mountains are a subrange of the Appalachians that run through parts of North Carolina and Tennessee.

HIGHLIGHTS: Skyline Drive,

Hiking, Camping, Wildlife

observation, Scenic mountain

views

HIGHLIGHTS: Rock formations,

Hiking, Developed campground

HIGHLIGHTS: Jeep trails,

Scenic driving, Wildlife

observation, Camping,

Paddling, Hiking

HIGHLIGHTS: Scenic driving, Wildlife, Hiking, Camping

HIGHLIGHTS: Skyline Drive, Hiking, Camping, Wildlife observation, Scenic mountain views

Just 75 miles from the bustle of Washington, D.C., Shenandoah National Park is an escape to recreation and re-creation. Cascading waterfalls, spectacular vistas, quiet wooded hollows all encourage visitors to take a hike, meander along Skyline Drive, or picnic with the family. 200,000 acres of protected lands are haven to deer, songbirds, the night sky–and you.

Shenandoah has developed campgrounds, easy short hikes and strenuous long hikes, and lots of natural beauty, but one of the unique things about it is that the park is actually centered around a paved scenic road that follows the contours of the mountain tops, called “Skyline Drive.” The road runs 105 miles north and south along the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains and is the only public road through the park.

In 1924 the search for a national park site in the east brought the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Their job was to find a site accessible to the 40 million Americans living in eastern cities including Washington, DC. The committee recommended the site that is today visited by millions of Americans each year, Shenandoah National Park. As part of that recommendation the committee, recognizing the proliferation of the automobile, suggested that the “greatest single feature” of the proposed park should be a “sky-line drive along the mountain top, following a continuous ridge and looking down westerly on the Shenandoah Valley…and also commanding a view of the Piedmont Plain stretching easterly to the Washington Monument.” Construction of such a roadway was a pioneering work of landscape architecture and engineering, as well as a famous work-relief project.

Work was begun before the park was even established using emergency employment relief funds, and continued by the boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps who spent thousands of hours building beautiful rock walls and landscaping sweeping overlooks to make Skyline Drive the experience it has been for over 75 years.

Driving it straight through without stops takes about three hours on a clear day. As you travel along Skyline Drive you will notice mileposts on the west side of the road that help visitors navigate the Park and locate areas of interest. There are 75 overlooks along the way as well as connections to all the major visitor centers, campgrounds, lodges, picnic areas and most trailheads. The central section of the drive, between Thornton Gap and Swift Run Gap, is a land of superlatives – highest park elevation, highest point on Skyline Drive, most land mass and arguably the best views, too.

HIGHLIGHTS: Rock formations, Hiking, Developed campground

Natural Chimneys Park in Mt. Solon, Virginia, is the site of a natural rock formation that includes seven rock “chimneys” ranging in height from 65 to 120 feet above ground level. The chimneys are formed from limestone that began to accumulate and harden about 500 million years ago when the region was underwater. It’s hard to imagine, but the Shenandoah Valley was once the floor of a great inland sea. Centuries ago, as that sea receded, the forces of nature carefully etched out an awe-inspiring formation of solid rock. Enormous upward pressures of magma and widespread geologic upheaval, which created the Appalachian Mountains combined with erosive forces of water and destroyed weaker layers of stone. Eventually, this created the rock chimneys which can be seen today.

The seven Natural Chimneys tower as much as 120 feet above the pastoral terrain of the Shenandoah Valley, offering onlookers a sight unrivaled in majesty. Viewed from one angle, the formations resemble enormous chimneys standing in bleak contrast to the greenery of the Valley. Take a few steps, though, and the chimneys are transformed into the massive turrets of a foreboding medieval castle.

The park, located along the North River, also has a 145-site campground and hiking trails.

HIGHLIGHTS: Jeep trails, Scenic driving, Wildlife observation, Camping, Paddling, Hiking

For off-roaders the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest is the area destination for trails of varying levels of challenge — from scenic dirt roads to more technical driving, there are a plethora of options (you can get a good idea by checking the area on an app like OnX Offroad that has trail ratings and descriptions). The GWJNF actually covers over 1.8 million acres of Appalachian forests in Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. We will just highlight a few of the places we enjoy.

Peters Mill Run is a Jeep Badge of Honor Trail and part of the Peters Mill Run and Taskers Gap OHV Trail System, the largest OHV trail system in the state of Virginia. There are 36 miles of rugged adventure with opportunities for Jeeps and other 4-wheeled drive vehicles, UTVs, ATVs and motorcycles. OHV riders will find challenges in steep, rocky and narrow trails, while others can enjoy trails that were once forest roads. All travelers will find mountain vistas, scenic rock outcroppings and the cool shade of deep forest.

The GWJNF is an administrative entity combining two U.S. National Forests into one of the largest areas of public land in the Eastern United States. In addition to the OHV trail system, the GWJNF also has miles of unpaved forest roads to explore and a lot of dispersed camping options as well as developed campgrounds.

We like exploring the area around Reddish Knob, a beautiful overlook high up on the mountain top. There is some great dispersed camping around Braley Pond, then following the “Reddish Knob” route starting on Braley Pond Road, we can enjoy the dirt roads all the way up to the “Knob.” After continuing on dirt from Reddish Knob to Flagpole Knob there are a few different options–we like going all the way to Switzer Lake. For those who prefer the “comforts” of a campground, there is a nice primitive campground at Hone Quarry.

George Washington National Forest was established on May 16, 1918, as the Shenandoah National Forest. The forest was renamed after the first President on June 28, 1932. Natural Bridge National Forest was added on July 22, 1933. Jefferson National Forest was formed on April 21, 1936, by combining portions of the Unaka and George Washington National Forests with other land. In 1995, the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests were administratively combined.

The border between the two forests roughly follows the James River. The forest is within a two-hour drive for over ten million people and thus receives large numbers of visitors, especially in the region closest to Shenandoah National Park.

HIGHLIGHTS: Scenic driving, Wildlife, Hiking, Camping

The Blue Ridge Parkway is a paved highway running from Virginia through North Carolina to the boder with Tennessee. The road “connects” the Shenandoah National Park with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, following the scenic route along the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

This route offers a slow-paced and relaxing drive revealing stunning long-range vistas and close-up views of the rugged mountains and pastoral landscapes of the Appalachian Highlands. The Parkway meanders for 469 miles, protecting a diversity of plants and animals, and providing opportunities for enjoying all that makes this region of the country so special.

When construction of the Parkway began in 1935, the Blue Ridge and Southern Appalachian region had been scarred by floods, fires, excessive logging, and the accompanying hillside erosion. The Parkway was, in many ways, a restoration project. And the landscape architects and engineers who created it thought of this project as more than just a road. Their mission was “to reveal the charm and interest of the American countryside and mountain living”. The Parkway was designed to blend into a protected corridor, and to give the impression that the park boundary extended to the horizon.

The Parkway incorporates several recreation areas, some exceeding 6,000 acres, and contains eight tranquil and scenic campgrounds which offer ready access to miles of hiking trails for those who want to explore on foot. Most campgrounds are at elevations greater than 2,500’, which means that temperatures are usually cooler than the surrounding area.

Along the Parkway, you can navigate using the numbered Mileposts. The 0 Milepost marker is at Rockfish Gap immediately south of Shenandoah National Park. Each mile is numbered progressively southward on the Parkway to its southernmost point at milepost 469 at Cherokee. There are some great planning resources keyed to the mileposts at the Blue Ridge Parkway Association site.

Just 75 miles from the bustle of Washington, D.C., Shenandoah National Park is an escape to recreation and re-creation. Cascading waterfalls, spectacular vistas, quiet wooded hollows all encourage visitors to take a hike, meander along Skyline Drive, or picnic with the family. 200,000 acres of protected lands are haven to deer, songbirds, the night sky–and you.

Shenandoah has developed campgrounds, easy short hikes and strenuous long hikes, and lots of natural beauty, but one of the unique things about it is that the park is actually centered around a paved scenic road that follows the contours of the mountain tops, called “Skyline Drive.” The road runs 105 miles north and south along the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains and is the only public road through the park.

In 1924 the search for a national park site in the east brought the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Their job was to find a site accessible to the 40 million Americans living in eastern cities including Washington, DC. The committee recommended the site that is today visited by millions of Americans each year, Shenandoah National Park. As part of that recommendation the committee, recognizing the proliferation of the automobile, suggested that the “greatest single feature” of the proposed park should be a “sky-line drive along the mountain top, following a continuous ridge and looking down westerly on the Shenandoah Valley…and also commanding a view of the Piedmont Plain stretching easterly to the Washington Monument.” Construction of such a roadway was a pioneering work of landscape architecture and engineering, as well as a famous work-relief project.

Work was begun before the park was even established using emergency employment relief funds, and continued by the boys of the Civilian Conservation Corps who spent thousands of hours building beautiful rock walls and landscaping sweeping overlooks to make Skyline Drive the experience it has been for over 75 years.

Driving it straight through without stops takes about three hours on a clear day. As you travel along Skyline Drive you will notice mileposts on the west side of the road that help visitors navigate the Park and locate areas of interest. There are 75 overlooks along the way as well as connections to all the major visitor centers, campgrounds, lodges, picnic areas and most trailheads. The central section of the drive, between Thornton Gap and Swift Run Gap, is a land of superlatives – highest park elevation, highest point on Skyline Drive, most land mass and arguably the best views, too.

Natural Chimneys Park in Mt. Solon, Virginia, is the site of a natural rock formation that includes seven rock “chimneys” ranging in height from 65 to 120 feet above ground level. The chimneys are formed from limestone that began to accumulate and harden about 500 million years ago when the region was underwater. It’s hard to imagine, but the Shenandoah Valley was once the floor of a great inland sea. Centuries ago, as that sea receded, the forces of nature carefully etched out an awe-inspiring formation of solid rock. Enormous upward pressures of magma and widespread geologic upheaval, which created the Appalachian Mountains combined with erosive forces of water and destroyed weaker layers of stone. Eventually, this created the rock chimneys which can be seen today.

The seven Natural Chimneys tower as much as 120 feet above the pastoral terrain of the Shenandoah Valley, offering onlookers a sight unrivaled in majesty. Viewed from one angle, the formations resemble enormous chimneys standing in bleak contrast to the greenery of the Valley. Take a few steps, though, and the chimneys are transformed into the massive turrets of a foreboding medieval castle.

The park, located along the North River, also has a 145-site campground and hiking trails.

For off-roaders the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest is the area destination for trails of varying levels of challenge — from scenic dirt roads to more technical driving, there are a plethora of options (you can get a good idea by checking the area on an app like OnX Offroad that has trail ratings and descriptions). The GWJNF actually covers over 1.8 million acres of Appalachian forests in Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. We will just highlight a few of the places we enjoy.

Peters Mill Run is a Jeep Badge of Honor Trail and part of the Peters Mill Run and Taskers Gap OHV Trail System, the largest OHV trail system in the state of Virginia. There are 36 miles of rugged adventure with opportunities for Jeeps and other 4-wheeled drive vehicles, UTVs, ATVs and motorcycles. OHV riders will find challenges in steep, rocky and narrow trails, while others can enjoy trails that were once forest roads. All travelers will find mountain vistas, scenic rock outcroppings and the cool shade of deep forest.

The GWJNF is an administrative entity combining two U.S. National Forests into one of the largest areas of public land in the Eastern United States. In addition to the OHV trail system, the GWJNF also has miles of unpaved forest roads to explore and a lot of dispersed camping options as well as developed campgrounds.

We like exploring the area around Reddish Knob, a beautiful overlook high up on the mountain top. There is some great dispersed camping around Braley Pond, then following the “Reddish Knob” route starting on Braley Pond Road, we can enjoy the dirt roads all the way up to the “Knob.” After continuing on dirt from Reddish Knob to Flagpole Knob there are a few different options–we like going all the way to Switzer Lake. For those who prefer the “comforts” of a campground, there is a nice primitive campground at Hone Quarry.

George Washington National Forest was established on May 16, 1918, as the Shenandoah National Forest. The forest was renamed after the first President on June 28, 1932. Natural Bridge National Forest was added on July 22, 1933. Jefferson National Forest was formed on April 21, 1936, by combining portions of the Unaka and George Washington National Forests with other land. In 1995, the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests were administratively combined.

The border between the two forests roughly follows the James River. The forest is within a two-hour drive for over ten million people and thus receives large numbers of visitors, especially in the region closest to Shenandoah National Park.

The Blue Ridge Parkway is a paved highway running from Virginia through North Carolina to the boder with Tennessee. The road “connects” the Shenandoah National Park with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, following the scenic route along the top of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

This route offers a slow-paced and relaxing drive revealing stunning long-range vistas and close-up views of the rugged mountains and pastoral landscapes of the Appalachian Highlands. The Parkway meanders for 469 miles, protecting a diversity of plants and animals, and providing opportunities for enjoying all that makes this region of the country so special.

When construction of the Parkway began in 1935, the Blue Ridge and Southern Appalachian region had been scarred by floods, fires, excessive logging, and the accompanying hillside erosion. The Parkway was, in many ways, a restoration project. And the landscape architects and engineers who created it thought of this project as more than just a road. Their mission was “to reveal the charm and interest of the American countryside and mountain living”. The Parkway was designed to blend into a protected corridor, and to give the impression that the park boundary extended to the horizon.

The Parkway incorporates several recreation areas, some exceeding 6,000 acres, and contains eight tranquil and scenic campgrounds which offer ready access to miles of hiking trails for those who want to explore on foot. Most campgrounds are at elevations greater than 2,500’, which means that temperatures are usually cooler than the surrounding area.

Along the Parkway, you can navigate using the numbered Mileposts. The 0 Milepost marker is at Rockfish Gap immediately south of Shenandoah National Park. Each mile is numbered progressively southward on the Parkway to its southernmost point at milepost 469 at Cherokee. There are some great planning resources keyed to the mileposts at the Blue Ridge Parkway Association site.

Street-legal vehicles on dirt forest roads. All OHVs in the Peters Mill Run and Tasker Gap OHV trail system.

Camping at campgrounds and some dispersed camping in the GWJNF.

Gas, food and water are all easily accessible.