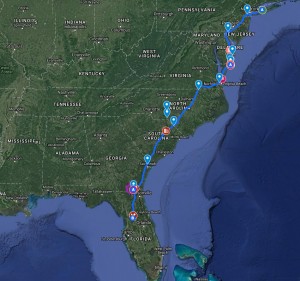

The locations featured in this series were waypoints along a roadtrip route from Long Island NY to Ocala FL. The original trip was done over two weeks in December of 2016 and the round trip route covered roughly 2,500-miles. Most of the journey was on pavement, with the locations featured here being the off pavement highlights. The primary goal of the trip was to explore a section of the Ocala National Forest and work on mapping skills.

The wind was sharp and blowing a cold mist that made it hard to tell if it was raining or not as I drove towards the beach on a very un-beach-like winter day. I was headed to a tiny strip of sand, a small barrier island on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. The Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is part of the Assateague Island National Seashore, a group of federally managed wilderness lands along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The area is split across Maryland and Virginia, with the larger Assateague Island on the Maryland side and the smaller Chincoteague shared by both states.

The fragile strips of land that make up this National Seashore are “barrier islands” — long, narrow, offshore deposits of sand or sediments that parallel the coast line. Some barrier islands can extend for 100 miles (160 km) or more. The Virginia Barrier Islands, of which Chincoteague is a part, are a continuous chain of long, thin, low-lying, sand and scrub islands separated from one another by narrow inlets and from the mainland by a series of shallow marshy bays along the entire coast of the Virginia end of the Delmarva Peninsula, terminating to the south at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. As the first line of defense during storms that threaten coastal communities, these islands are very important for reducing the devastating effects of wind and waves and for absorbing storm energy. They are also an important ecological region providing a marine habitat that supports commercial fishing, as well as birds, sea turtles and other wildlife species.

To reach the barrier island, I cross a maze of land and water — a series of marshes and small islands connected by bridges and causeways. A total of seven “bridges” must be crossed to get into the Wildlife Reserve, and driving along the low causeways sometimes feels like I am driving on the water itself. The land and water seem intertwined, as if trying to define their own borders and edges under the day’s threatening sky. From the marshlands I can see the thin strip of land in the distance.

Entering the protected area of the refuge, I make a stop at the Visitor Center to get an “Over-Sand Vehicle” (OSV) permit, which is required for beach driving in the refuge’s designated “Over-Sand Vehicle Zones.” Permitted vehicles must carry sand-specific recovery gear and follow certain protocols while using the OSV zone. I also confirm the high-tide times for the day with the refuge staff. Knowing the timing of the tides is critical because the barrier island gets so narrow in some places that a vehicle could be trapped during a high tide. With assurance that high-tide had just passed and wasn’t due again until the evening, I set off for the “beach.”

Although the beach is a major attraction for visitors, the 14,000 acre refuge actually contains multiple terrains and habitats, including dunes, marsh and maritime forest. There are some short hiking/biking trails in the woodlands where visitors are likely to see wildlife, and as I drive through the loblolly pine I notice a little Delmarva Peninsula fox squirrel. Just removed from the “endangered” list in 2015, the Delmarva fox squirrel feeds on the loblolly pine cones, and has been able to recover from the risk of extinction thanks to the concerted conservation efforts of the states, local landowners and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). In addition to supporting breeding populations of the Delmarva squirrel, the refuge provides an important habitat for the threatened piping plover, the American bald eagle and the American peregrine falcon which is seen quite frequently during its annual autumn migration. In fact, refuge management programs are designed to provide feeding and resting areas for birds in migration.

Beyond the forest blends into wetlands including both salt and fresh water areas which are a vital for many migratory birds. It was raining as I drove along the edge of the waterway, and on first glance there appeared to be a bunch of puffy white flowers on the bushes, but as I looked closer I realized they were a multitude of white birds. They were perched on the bushes, seemingly “hunkered down” and waiting for the rain to stop. Apparently birds, even shorebirds, don’t like the rain — especially if it is heavy or cold, as it is in late December. Though bird feathers are somewhat water resistant and a light rain is no problem, the winter rain can be uncomfortable. Birds stay warm by trapping tiny pockets of air under their feathers, and if those pockets fill with cold water instead of air, the bird will get cold very quickly. So they look for shelter in bushes, reeds, or nesting cavities and fluff up their feathers to stay warm. In heavier rain they take up a a heat-conserving position, sleeking down their feathers and withdrawing the head to minimize the body’s exposure to the raindrops. Shorebirds often huddle close together, all in this posture. While they perched motionless on the bushes I could identify a few different types of wading birds including herons and egrets, but there were others I was unsure of.

Continuing on to the narrow strip of sand that defines the edge of the barrier island near Tom’s Cove, the landscape was transformed into a harsh desolate empty space. The beach was deserted. The cold wet weather had given me a unique opportunity to experience this incredible place in solitude. I aired down the tires then turned south to follow the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. It was cold and windy and wet, and though probably not technically “raining,” the wind and the “mist” made it rather uncomfortable — the overall feeling was of an inhospitable place in a very remote wilderness.

The present refuge islands began forming around 8,000 years ago as landforms roughly similar in appearance to today, exhibiting beach and dune lines on the eastern face that protect a thin strip of grass and scrub, then the band of maritime forest and salt marsh to the west. However, the size and shape of the island undoubtedly differed. The area has always been somewhat wild, but evidence suggests it was probably seasonally occupied beginning about 1,000 years ago by several tribes including the Chincoteague, and Assateague for whom these islands are named.

As I drove down the beach along the narrowest spot between the bay and the ocean, it seemed like the land disappeared into converging water. I could almost feel the fragility of the tiny strip of sand stubbornly fighting off the power of the Atlantic. Less than a quarter of a mile separated ocean from bay. I could see the water on both sides, and the unsettled weather seemed to emphasize my tenuous position. I felt very small and vulnerable in my little Jeep in the midst of all this water, almost as if one really big wave could swallow us up or wash us away.

And in fact, barrier islands are dynamic, not stationary. Just as waves and water built the island, they also are constantly moving it around. A study of historical maps show how “radically” these islands have changed. The part of Assateague south of Morris Island did not even exist prior to 1693. By 1820 Morris Island included the current area of the Farm Fields Impoundments, which with the Lighthouse Ridge area, were the primary barrier islands that protected Chincoteague. Then just a few years later, in 1832, charts show the channels between those islands blocked, making the island continuous all the way down to the present Woodland Trail area — a hurricane driven tidal wave in 1821 was the primary cause of that dramatic change. Fishing Point, the beginnings of Tom’s Hook, did not begin to grow until sometime between 1873 and 1882. And this growth and reshaping due to sand migration, coastal storms and rising sea levels continues today.

In addition to daily tidal movements, there are seasonal movements as well. Gentle summer waves bring sand from offshore sandbars, forming wide beaches. In winter, waves pack more energy and the pounding on the beaches makes them narrower as sand is carried back out and deposited on the sandbars. Major storms can bring in heavier grains of black sand made up of minerals that make the beach look dirty. Erosion has allowed storms to overwash the dunes and the modern Toms Cove Visitor Center has already had to be moved three times and the parking lot redesigned.

The contradiction between the eternal and the ephemeral was emphasized by the rhythm of the waves crashing on sand, reaching out like fingers of a hand to try to join the water on the other side of the island. Dark threatening skies and choppy water seemed foreboding as I continued my drive. It almost seemed like the the water was coming closer, even though I knew the tide was actually going out. I followed the waters edge and the old tire tracks southward toward the area known as “the hook.” Though there were a lot of tracks, they were not fresh and soft sand had already started filling them in. In some places deep ruts held pockets of very soft sand creating a strange combination, and I found it better to slightly offset these existing tracks. I didn’t have to worry about “widening the trail” as the whole area marked off with plastic poles was considered the “trail.”

The sea was getting more agitated and the waves were crashing onto the beach with more force. My thoughts turned to shipwrecks. Shipwrecks along the unpredictable offshore shoals were frequent in the 1800s as coastal trade developed, and “wrecking”, or stripping stranded ships of their cargo, became a common practice. In 1833, the first Assateague Lighthouse was constructed to warn ocean travelers of the dangerous shoals offshore and the U.S. Lifesaving Service was established in 1848 in response to the increasingly recognized need for a system to rescue mariners and passengers of wrecked vessels. Fully manned and equipped stations began to be established in the late 1800s and dedicated surfmen lived with their families near the stations, patrolling the beaches regularly to signal warnings if ships came too close. The surfmen also rescued crews and protected ships and cargoes when disaster struck. The U.S. Coast Guard took over those responsibilities in 1915. By 1920 the Hook had grown into a curved landform that forced Coast Guard boats to take an increasingly roundabout journey to rescue shipwreck survivors and a new station was built near what was the end of the island at that time. It was closed in 1967 and according to my map I should be able to see it as I entered the Hook.

The Hook is a larger land mass where the sandy shoreline blends into dunes and beach grasses grow securing the sand. I left the Jeep on the beach and walked across the grassy area towards the bayside. There is no clear trail here and I just wander a bit through the beauty of this wilderness area, appreciating the fact that the nasty weather has gifted me with solitude. The only sounds I hear are the sounds of the wind and sea. I could see the structures of the old Coast Guard station in the distance beyond the beach dunes.

It didn’t take long to get from one side of the “island” to the other. The Coast Guard installation consisted of a tower, a couple of buildings and a crumbling dock. The structure has been determined eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, and was used as a visitor facility by the NPS until the road began to be washed out on a regular basis in the 1980s. When NPS established the current visitor center it closed this facility, leaving it empty but not actually “abandoned.”

The old topo map, which dates from 1981, indicates the ruins of a fishing factory on the bay side too, but I can’t find any evidence of it. The barrier islands were only permanently inhabited briefly. During the 1800s, a community of people lived on Assateague Island and with the construction of the lighthouse, a village became established northeast of the structure. Oyster and other commercial fisheries were developed, and the population grew to 225 by the turn of the century with a school, store, and churches. Some residents worked in fish oil processing factories on the ever-growing land formation that eventually became the Hook. The last of those factories closed in 1929 when most of the area south of the Lighthouse was purchased by an absentee landowner who hired a caretaker to prevent local residents from trespassing — essentially blocking all access to fish in Toms Cove. The resulting hardship soon led to wholesale abandonment of the village. Most of its buildings were moved on rafts to Chincoteague Island. Aside from Coast Guard personnel at the light station and lifesaving stations, there were no longer any year-round residents. According to NWR historians, the sites of the fish oil plants have all eroded into the cove with the westerly migration of the island.

The wilderness has reclaimed any evidence of the inhabitants. I explored a bit further off into the beach dunes but did not disturb the lonely structures of the Coast Guard station sitting forlornly on the waters edge. Instead I turned to wander along the calm of the bayside for a while. Wind and water shaped this rugged landscape creating an unsettling beauty. I considered the scoured dunes, exposed roots and wavering grasses where the beach begins the transition from marine to upland environments. By definition, barrier islands protect the lagoons and salt marshes on the bayside from the forces of the open sea. But the islands themselves are increasingly threatened by the effects of climate change that causes sea levels to rise with increasing intensity.

According to the US Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Comprehensive Conservation Plan for the refuge, the rise in relative sea level for the Delmarva Peninsula will have a significant negative impact on the barrier island system here. The lowest tidal wetlands will be submerged with an increase in erosion of coastal beaches, more frequent flooding of the lowlands, and alterations in salinity regimes in coastal waters that can change the local ecology. While this process has occurred in the past, the pace at which these changes are happening has accelerated and their magnitude has increased. The shoreline of the barrier island, already impacted by erosion from the current sea level rise rate, will become even more vulnerable. If the rate increases by as little as 2mm/year, the island may break up into smaller sections! As I headed back towards the Jeep at the waters edge, I couldn’t help but reflect on the contradictions of a place that seems simultaneously eternal and ephemeral.

> CONTINUE: TO OKEFENOKEE SWAMP

WHERE WE ARE

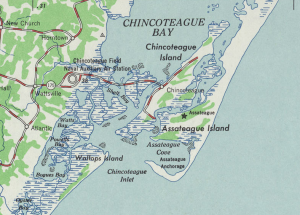

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refugee is part of the Assateague Island National Seashore, a collection of fragile barrier islands along the Atlantic coast of Maryland and Virginia leading to the Chesapeake Bay.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

HIGHWAY 13 / CHINCOTEAGUE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE – 23 miles one way – Plan on a minimum visit time of 3 hours once at the refuge

(click map for larger view of route)

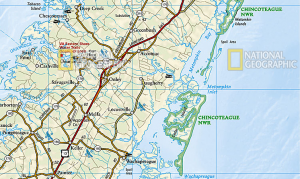

The drive is an easy scenic trip, on paved roads until the final Over-Sand Vehicle (OSV) Zone along the beach. There are no navigational challenges and this trip can easily be done using only the OSV map diagram provided by the refuge. The 13-mile segment from Highway 13 to the visitor center follows a very scenic route that goes around NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility before crossing through a maze of picturesque wetlands connected by a series of causeways and bridges leading to Chincoteague Island, a populated area full of beach homes, restaurants, shops and water-based recreational facilities. Beyond the town, the road continues across another bridge onto the barrier island where the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is located. A paved road continues from the main visitor center near the refuge entrance for roughly 2.5 miles to the beach access point at Tom’s Cove. The beach access point leads to the OSV area which is clearly marked, and the route via sand goes south for about 2.5 miles to the base of the “hook” and then for about 5 more miles around the to a fishing access point on the bay side beyond which you cannot drive. The drive on sand is generally easy for a properly equipped and aired down vehicles and there are no obstacles apart from pockets of softer sand here and there. Note that it IS CRITICAL to be aware of the high tide times and be off the beach well before it peaks because the incoming tide can trap a vehicle on the narrowest stretches of the beach route.

THE DELMARVA PENINSULA

The geographic region we are driving through is known as the Delmarva Peninsula. The name “Delmarva,” is a combination of the three state names that share the peninsula: Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. Heading southward into Virginia, it narrows into a fingerlike projection that separates the lower Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. It is wild and remote and for many generations seafaring watermen, farmers, and their hard-working families have sustained themselves on the waters of the bay and ocean and the riches of the Eastern Shore soil. Only four decades have passed since mainland Virginians gained access to the peninsula via the 17.6-mile Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel and the lack of access has served as a barrier to commercialism and development, leaving this part of the Eastern Shore in a more natural state. Regionally, the Delmarva Peninsula lies in the Atlantic Coastal Plain, a seaward sloping province bounded on the west by a fall line and the Chesapeake Bay, and on the east by the Atlantic Ocean. The peninsula extends about 200 miles in a north-south direction and includes the State of Delaware and the eastern shores of Maryland and Virginia. The surficial sediments of Assateague Island are discontinuous Holocene Series deposits (tidal marsh and barrier sands). The subsurface sediments of the Delmarva Peninsula form a wedge of unconsolidated sands, silts, and clays that is over 7,000 feet thick and ranges in age from Cretaceous to Tertiary. The subsurface sediments rest on a seaward sloping basement of Paleozoic crystalline rocks. The basement is folded and faulted into a series of northwest-southeast trending ridges and depressions. The Delmarva Peninsula was formed about 14,000 to 18,000 years ago during the last glacial retreat, when rising sea levels filled the large valley of the lower Susquehanna River, which became the Chesapeake Bay, thus isolating the area from the mainland. Consequently, the Delmarva Peninsula coastline with its barrier islands has changed dramatically since the retreat of the last glacial ice sheets and the melting of the polar icecaps. Sea level has risen more than 300 feet and the shoreline has shifted approximately 50 miles to the west. In general, the continued sea level rise will result in the submerging of the continental shelf and shifting barrier islands landward and upward.

ABOUT THE CHINCOTEAGUE NWR

Located on the southern end of 37-mile-long Assateague Island, within the boundaries of Assateague Island National Seashore, the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1943 to provide habitat for migratory birds. Among the thousands of birds that come here, the snow geese (Chen caerulescens), with their beautiful white plumage and black primary wing feathers, are a big favorite. Chincoteague, managed jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Parks Service, is one of the most visited refuges in the United States. It includes more than 14,000 acres of beach, dunes, marsh, and maritime forest. The refuge maintains several miles of hiking and biking trails. Hikers have 15 miles of trails to explore, and half of those are paved for bicycling and wheelchairs. The 3.2-mile, paved Wildlife Loop gives hikers and bikers access to Snow Goose Pool and Swan Cove. Vehicles are permitted on the loop between 3 p.m. and dusk. The waterways and ponds beside the road always hold a snowy egret, or the elegant great blue heron, or perhaps a flock of Canada geese. In addition to the Wildlife Loop, other hiking opportunities include the 1.6-mile Woodland Trail loop (walking and bicycling allowed) and the 0.25-mile (one-way) Lighthouse Trail to the photogenic Assateague Lighthouse. Built in the 1860s, this tower lighthouse with its alternating red and white rings still operates with a flashing light. The pine forests of the refuge hold white-tailed deer and the much smaller Sika deer. Sikas, which are actually an Oriental species of elk, were released on Assateague Island in the 1920s. Wild ponies also roam the island and are a common sight as they graze the salt marshes. Popular legend tells of ponies that escaped a shipwrecked Spanish galleon and swam ashore, however most historians believe the ponies are descendants from animals belonging to settlers who used the island for grazing livestock in the 17th Century to avoid fencing regulations and taxation. Interpretive programs that explain the barrier island natural and cultural history are held outdoors and in the refuge auditorium. The refuge is open daily, year-round. Hours vary according to season, but they are roughly pre-dawn to just after nightfall. The island is accessible from the mainland from both the Maryland end and the Virginia end, but there are no roads on the island that connect the north and south ends (in fact, a fence on the state line keeps even the wild ponies that roam the island from mixing).

THE DELMARVA FOX SQUIRREL

The Delmarva Fox Squirrel is a large, gray squirrel that lives in quiet forests on the Delmarva Peninsula. Larger than most squirrels, it can grow to 30 inches in length and weigh up to 3 pounds. It has a steel or whitish gray body and a white belly with short, thick, rounded ears. More shy than the common eastern grey squirrel, the Delmarva prefers quiet wooded areas, especially mature loblolly pine and hardwood forests with an open understory. It spends a considerable amount of time on the ground, and instead of jumping from tree to tree, Delmarva fox squirrels will descend down a tree and travel on the ground to the next tree. While their historic range extended as far north as southern New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania, today they are only found in small isolated populations on the Delmarva Peninsula, and were listed as endangered species until 2015.

OVER-SAND VEHICLE ZONES

Vehicle use on the beaches of the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge is by permit only. Permits may be obtained at the visitor centers in the Seashore and Refuge and the North Beach Ranger Station (call 757-336-6122 for current information). In order to be permitted, you are required to carry specific recovery equipment in your vehicle including: a shovel, jack with a board or other appropriate support to keep it from sinking in soft sand, a tire pressure gauge (recommended 15 PSI or less for the beach), and a strap or tow rope. When driving on the beach, all sand dunes and vegetated areas are considered closed even if located within the designated OSV zones. Vehicles must stay east of the black and white posts. There is a speed limit of 25 mph which must be reduced to 15 mph whenever coming within 100 feet of vehicles, wildlife, pedestrians or people on horseback. When two vehicles approach in the same track, both operators must slow and the operator with the ocean on his right must yield the right-of-way by pulling out of the track. Note that the OSV zones have “density” limits to regulate the number of vehicles on the beach at any one time (145 vehicles on the Maryland side and 48 vehicles on the Virginia side) and purchase of an OSV permit does not guarantee access. Be aware that vehicle density limits are reached frequently during summer, especially on weekends and holidays. The National Park Service offers the following “tips” for over-sand driving:

• Lower tire pressure to 15PSI

• Carry four boards 2” x 6” x 36” for placing under tires when stuck (we recommend Maxtrax instead)

• After stopping vehicle, back up several feet before proceeding forward

• Walk across suspected soft sand first, to make sure that it will hold your vehicle

• Do not spin tires. Spinning tires only makes them dig deeper into the sand, increasing the chance that the vehicle’s frame will bottom out

• Driving in the tracks of another vehicle is easier than driving through fresh sand

• Carry water displacement spray for drying wet engine electrical parts

• Do not drive in salt water

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provide the best detail and include the topography that defines the landscape:

Chincoteague – 1:100,000 topographical map

Eastville = 1:250,000 topographical map

For a good overview of the area the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Delmarva Peninsula map is useful. This printed map comes on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and covers all major recreation areas for the Peninsula and Chesapeake Bay region, including all state parks, state wildlife areas, national wildlife areas, and key recreation access points. Locations for camping, boating, paddling, hunting, biking, and fishing are also displayed.

BARRIER ISLAND FORMATION

Barrier islands are coastal landforms with a dune system formed by wave and tidal action parallel to the mainland coast. They usually occur in chains, consisting of anything from a few islands to more than a dozen. Chains of barrier islands can be found along approximately thirteen percent of the world’s coastlines. These islands protect the coastlines and create areas where wetlands can flourish. A barrier chain may extend uninterrupted for over a hundred kilometers, excepting the tidal inlets that separate the islands. The length and width of barriers are determined by tidal range, wave energy, sediment supply, sea-level trends, and basement controls. Scientists have proposed numerous explanations for the formation of barrier islands and there are three major theories: offshore bar, spit accretion, and submergence. However there is agreement on the general requirements for barrier formation. They develop most easily on wave-dominated coasts with a small to moderate tidal range. Along with a small tidal range and a wave-dominated coast, there must be a relatively low gradient shelf. Otherwise, sand accumulation into a sandbar would not occur and instead would be dispersed throughout the shore. An ample sediment supply is also a requirement for barrier island formation. The last major requirement for barrier island formation is a stable sea level. It is especially important for sea level to remain relatively unchanged during barrier island formation and growth. If sea level changes are too drastic, time will be insufficient for wave action to accumulate sand into a dune — constant sea levels allow the waves to concentrate the sand into one location.

BARRIER ISLAND HABITATS

A barrier island consists of four different habitat zones: salt marsh, barrier flat, dunes and beach.

The “Salt marsh” is a low-lying area on the sound-side of a barrier island that is stabilized by cord grasses and flooded by daily tidal activity. It helps purify runoff from mainland streams and rivers. The salt marshes that you find on the sound sides of barrier islands are similar to those found on the coastal mainland.

The “barrier flat” is formed from sediment pushed through the dunes by storms and stabilized by grasses. The primary vegetation includes cordgrass and sawgrass. It is often flooded daily during high tide. The muds and sediments are full of anaerobic bacteria (there is little oxygen in the sediments) which decompose the rich organic material in the sediments. Animals that live in the wet muds filter-feed bacteria and plankton from the tidewaters or feed on bacteria in the muds; these animals include clams, mussels, snails and worms. Various fish come and go with the tides. Fiddler crabs feed on the bacteria in the muds. Ghost crabs and blue crabs feed on the bacteria, small invertebrates and small fish. Various birds (seagulls, egrets, pelicans) feed on the fish, crabs and invertebrates.

The “dunes” consist of sand that has been carried and deposited by winds. Dunes are naturally stabilized by plants and sometimes artificially by fencing. They can be flooded during storms but mostly receive moisture from rain and surf. The dunes are a relatively hostile environment with high salt content, sandy soil and little fresh water. Plants such as sea oats and bitter pancum provide stability with root systems that hold the sand in place. Their shoots slow the winds, thereby allowing more sand to be deposited. This habitat is home to many crabs and birds, such as gulls and terns, that feed on other animals found there.

The “beach” is the ocean side of the island with sand deposited by wave action. The beach is somewhat like a desert in that it lacks fresh water, but a large portion gets covered almost entirely with salt water twice daily (the entire beach gets covered to the dune base during storms). Animals and plants in this environment (known as the intertidal zone, between tides) must endure long periods of exposure to salt water and drying air. On the beach, the only plant life you’ll see is some algae that get washed ashore. Bacteria live in the spaces between the sand grains where water from the surf percolates through. The animals on the beach itself include burrowing animals like mole crabs and clams that filter-feed during high tides, burrowing worms that feed on bacteria in the sand, scavenging crabs (ghost crabs) and various shorebirds (sandpipers, seagulls and pelicans) that eat the crabs, burrowing animals and offshore fish. (For more information see this NOAA site)

ISLANDS IN MOTION

The formation of barrier islands is complex and not completely understood. The current theory is that barrier islands were formed about 18,000 years ago when the last Ice Age ended. As the glaciers melted and receded, the sea levels began to rise, and flooded areas behind the beach ridges at that time. The rising waters carried sediments from those beach ridges and deposited them along shallow areas just off the new coast lines. Waves and currents continued to bring in sediments that built up, forming the barrier islands. In addition, rivers washed sediments from the mainland that settled behind the islands and helped build them up. But whatever the origin, barrier islands are constantly changing. Waves continually deposit and remove sediments from the ocean side of the island. Longshore currents that are caused by waves hitting the island at an angle can move the sand from one end of the island to another. For example, the offshore currents along the east coast of the United States tend to remove sand from the northern ends of barrier islands and deposit it at the southern ends. The tides move sediments into the salt marshes and eventually fill them in. Thus, the sound sides of barrier islands tend to build up as the ocean sides erode. Winds blow sediments from the beaches to help form dunes and into the marshes, which contributes to their build-up. Rising sea levels tend to push barrier islands toward the mainland. Hurricanes and other storms have the most dramatic effects on barrier islands by creating overwash areas and eroding beaches as well as other portions of barrier islands. The natural movement of barrier islands poses no problem until humans decide to put hotels, swimming pools, and highways on them. Then, somewhere down the road, it becomes necessary to build sea walls, to shore up dunes in front of buildings by pumping in sand from offshore, or to build rock jetties to keep the island from continuing to transport itself somewhere else. What engineers have found, though, is that for every mechanical thing done to make the island stay put, there is a reaction somewhere else. For instance, the rock jetties built on the southern end of the next barrier island to the north — the one that holds Ocean City — have caused wide beaches to pile up there. But, in turn, the adjacent northern end of Assateague is eroding severely and migrating toward the mainland at a much faster speed than it once did.

NOTE: This is the first in a series of segments highlighting destinations along a roadtrip route from Long Island, New York to the Ocala National Forest in Florida. These locations were all stops on a solo Jeep roadtrip made in December of 2016. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in December 2016 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.