A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< BACK: TO NORTHPOINT | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO HITE CROSSING >

It rained overnight. It started after 10pm and continued steadily until early morning. Luckily there had been no heavy downpours, and though things were wet, there were no gushing streams of water or messy mud bogs around camp. The air smelled good after the rain, and the silhouettes that define the canyon appeared sharp against the sky. As the sunrise began in earnest, strong light illuminated the retreating clouds with a strange glow. Watching nature’s light show I was reminded of a violent struggle between light and darkness, as sun and clouds mixed, all framed dramatically by bare twisted tree branches. The sun peeked out brightly underneath the thickest layer of clouds. And its golden orb was victorious in the end, lighting the canyons and deserts beyond with a welcome warm glow.

The whole landscape seemed transformed by the presence of the sun. The Orange Cliffs were appropriately orange and the contrast of red rock and blue sky was finally as it should be. Today would be my last full day inside the park, but only the first day that I could see it with the colors I was used to. With clear blue skies and no more rain in the forecast, I could finally relax and take my time to just appreciate the splendor of the place.

Leaving the Golden Staircase, I drove back along the way I had come, but it looked completely different. I stopped near the edge of the mesa for a last look down at the enormous fins of “Ernie’s Country” below. The strange terrain forms go on seemingly forever into the distance. It seemed like there were a million of those “fins” eroded into strange shapes, looking kind of like stalactites or stalagmites, but not in a cave. This uninhabited 30 square mile sandstone puzzle has been described as the most inhospitable land in the west. Wild, desolate and remote it is easy to see why it was once an ideal hideout for outlaws like Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch.

Until the Moab area reinvented itself as an outdoor adventure activity paradise, the only folks who came out here were cowboys and prospectors, and those involved in the mining industry. In the early 1900s Ernie Larson grazed his sheep on this scarce section of green, and its been known as “Ernie’s Country” ever since. Down there are a few precious springs named after Lou and Clell of the Chaffin family, important cattlemen here from 1919 to 1944. According to Ned Chaffin, who worked as a cowboy when it was still known as Under the Ledge, “One hundred and ten miles from the Maze to Green River, and you’d ride that horseback…three or four days to get out there and three or four days to get back. And while you were there you might just as well have been on Mars. You didn’t see anybody.”

When the park was established in 1964, the Maze, the Land of Standing Rocks and Horseshoe Canyon were not part of Canyonlands. These western wonderlands were added by Congress in 1971, along with strips on the north and southeast boundaries, and in 1995 the Park Service adopted a backcountry management plan intended to make the Maze experience primitive, by modern standards.

The solitude and remoteness of the area is one of the special qualities that the Canyonlands National Park works hard to preserve. A great deal of thought and legislation has gone into protecting this space as a “wilderness experience.” “Wilderness” is actually defined, in section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act, as a place that “has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation”. However, what the framers of the Wilderness Act specifically meant by solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation is not spelled out. According to some wilderness management experts, the precise meaning of solitude has been at the center of considerable debate. The range of meanings runs the gamut from a lack of seeing other people, to privacy, to freedom from societal constraints and obligations, to freedom from management regulations. However most people can agree that the concept encompasses attributes such as separation from people and civilization, inspiration (an awakening of the senses, connection with the beauty of nature and the larger community of life) and a sense of timelessness (allowing one to let go of day-to-day obligations, go at one’s own pace, and spend time reflecting). Primitive recreation stresses a reliance on personal skills to travel and camp in an area, rather than reliance on facilities or outside help, and the goal has been to provide opportunities for the physical and mental challenges associated with adventure and self direction as well as the personal growth that results from facing and overcoming obstacles.

The Maze demands self-reliance and preparation. The Park Service doesn’t want to attract more people here, and has an active policy of not really encouraging them, according to park officials interviewed by the Deseret News. The Maze District is considered the most remote and rugged area managed by the National Park Service outside of Alaska, and the goal is to keep it as a challenging place, a lonely place, and a place where one can really escape “civilization.” NPS wants this district to represent Canyonlands at its wildest.

Continuing my drive north, following the line of the Orange Cliffs, the trail was easy along a mostly flat dirt road on the canyon floor. The light and shadow brought the relief alive and the texture of the cliff wall practically glowed. I was not in a hurry to get anywhere, so when I came to a nice little overlook across from the Bagpipe Butte, I stopped to explore. I walked along the edge of a rocky outcropping towards the rock formation that now seemed so close. I had learned that even in terrain that at first glance seems impossible, there is usually a way to get around, over or through if you look carefully enough.

At the end of the ledge a pile of rocks seemed almost posed like some kind of giant cairn to mark the spot. Framed just right the enormous butte was tiny and the rocks in front of me were monumental. I hung out there for a little while just appreciating the place I was in, which somehow made me feel as if I was truly on top of the world, while emphasizing how really small and insignificant we are in all this vastness. In a way, I was invisible here, a speck, unremarkable and hidden in the monumental beauty of nature’s greatness. My journey had become an exercise in extreme solitude and self-reliance of the kind the framers of the Wilderness Act intended.

Looking out across the desert I could see other buttes marking my route in the distance like waypoints. I could confirm my exact location without even needing to look at a compass or GPS. The complexity of the terrain became a visual road map clearly guiding me ahead to my next destination. The Elaterite Butte would be my next “marker,” and from there I would turn to the east. Letting my mind play, I imagined these buttes were monuments with hidden meanings known only to the wind that sculpted them. I felt for a moment like a true explorer, seeing this place for the very first time. It was so silent I could hear the flapping of a bird’s wings as it soared above me.

Though access to the Maze requires a four-wheel drive vehicle, most of the terrain in this section of the trail is flat and straight, making for a very pleasant drive through a magnificent landscape. I could focus on my surroundings and see the nuanced transition from red dirt to white sand to grey rock and back again. I was learning how varied and vibrant “the desert” can really be.

This section of the Elaterite Basin includes a fossilized offshore sand bar roughly 250 feet thick and ten miles in length, which according to Donald Bears, author of a geological history of the Colorado Plateau, contains oil that sometimes seeps from the sandstone. These tar seeps are relatively rare in nature and the oil actually fills the “interstitial pores,” which are the spaces between individual sand grains. This form of oil is known as “elaterite,” a solid mixture of sandstone and petroleum that looks something like dirty asphalt, and though the area probably holds a significant volume of oil, the fact that it is dispersed over billions of grains of sand–with each pore holding only a tiny amount– makes it far too expensive to extract.

However, in the early 1900s, prospectors unaware of that detail noted the signs of underground oil where on hot days it could be visually seen seeping out of the earth. This “evidence” became a hot topic, many claims were filed, and in 1920 the Nequoia Oil Company brought a drilling rig in to search for the black gold. They spent a whole year drilling without striking oil, then went bankrupt leaving most of the men who worked for the company with an entire year’s wages unpaid!

At some points the trail was in the bed of the dry wash, and I was glad there was no more rain in the forecast, as it looked like the water could get pretty deep and I would have to come back this same way. Driving this route had a nice rhythm alternating between those flat easy wide open sections of trail and some more “interesting” jeep-y spots — though nothing actually difficult. I rarely needed to use 4 Lo and didn’t need the lockers at all (though they definitely might have come in handy on the road to Standing Rocks had I tried to go out to the Dollhouse). Throughout the day I was going up and down, making slight elevation changes, but I hadn’t really paid much attention to them while I was driving. Only afterwards, when I was trying to make sense of where I was in terms of the top, middle, or bottom of the nested canyons, did I give it any thought.

The riddle of the nested canyons was brought home to me as I came unexpectedly to a place that had seemed like flat rolling desert from further away, but actually concealed another vast hole in the ground — called “Horse Canyon” (which is distinct from “Horseshoe Canyon” that is another part of the park). It was right on the edge of the trail and in deep shadow and I realized that had I not been paying attention I could have almost driven right into it. Taking a little bit of time out to explore on foot, I realized when I looked back to the Jeep and the shadows of the rim of the canyon above us, that I was once again somewhere in the middle of a spiral of nested canyons — a three-dimensional “maze” indeed. The texture of the erosion was painterly in the afternoon light, creating a very impressionistic effect with bands of colors that seem like thick brush strokes on canvas.

Back on the trail, I continued along the edge of Horse Canyon as it turned and guided me to the Maze Overlook, the location of my campsite for the night. I had heard that it was a beautiful spot, but I was not prepared for the visceral emotion that natural beauty could inspire. My eyes widened and I was totally awestruck by the epic view that spilled out before me. Drawn to the otherworldliness of it all, I left the Jeep and walked towards it. Pillars of red rock dominated the scene like a ruin on the acropolis — these are the “Chocolate Drops.” Below it looked like the bottom of a giant scale Roman “Colosseum” with an underlayer of elaborate labyrinths–a seemingly infinite series of small canyon swirls of stone and ledges winding down into more canyons. Now I understood why they called it “The Maze.”

I could also see clearly why Backpacker, Outside magazine, Gear Patrol, and Men’s Journal all placed The Maze on their “10 Most Dangerous Hikes” lists. The dizzying swirl of rock ledges leading nowhere seemed to go on forever and I imagined that maybe no one has ever crossed it. Some areas might only be accessed by rappelling down from a helicopter. And the thought of being lost down there was nightmarish. Still, people do hike it, and my campsite was right near the access point down the Maze Overlook Trail. I decided to explore a little, though any serious hiking would have to wait till another longer trip. Walking along the rim and scrambling down some of the small rock ledges, I could see how little by little it would be possible to descend. The details of the maze were enticing, and I really wished I had more time, but it is not the hike to attempt un-prepared.

A solid knowledge of maps (and a GPS with waypoint “breadcrumbs”) is a pre-requisite for anyone planning to wander through the area full of dead-end canyons, sandstone fins and rock walls that all seem to look the same. The late afternoon sun playing with light and shadow transforms the appearance of the rock, and I realized that even if I saw what it looked like when I went down, it might look very different at another time of day. Perspectives also change from below and views are cut off by high cliffs, that make it impossible to see landmarks. Water is scarce and terrain is often impassable.

The rewards, however, are great for those who do make the journey down the steep slickrock trail to the bottom of South Fork Horse Canyon. The Harvest Scene Pictograph panel–painted at least 2,000 years–is only 2.9 miles from the trail in a nearby canyon called Pictograph Fork. And the opportunity to explore the depths of nature’s work-in-progress as it further etches away the sandstone walls of the labyrinth is alluring. Possibilities for exploration are only limited by time and capabilities. My walk would not that challenging, as I just meandered along the ledges for a while, following the contour of the land, actually, getting a feel for the place and a taste of the beauty enveloped in the solitude of the wild. Settling back into camp at the end of an incredibly fulfilling day, I watched the light work its magic on the Chocolate Drops and prepared for the moonrise, inspired by the grand scale of it all.

> CONTINUE: DAY FIVE — MAZE OVERLOOK TO HITE CROSSING

< BACK: TO NORTH POINT | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO HITE CROSSING >

WHERE WE ARE

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

GOLDEN STAIRCASE / MAZE OVERLOOK – 13 miles – Estimated drive time 2 hours

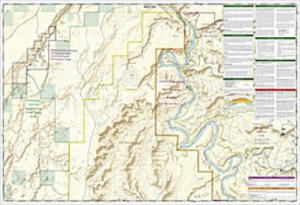

(click map for larger view of route)

Leaving Golden Staircase I travel back along the rim west about a mile before picking up the trail north. I follow the line of the Orange Cliffs continuing north through some varied terrain, passing Bagpipe Butte, and down into the Elaterite Basin. There are several small dry wash crossings, and a section where the trail runs in the wash for a bit. In general the drive is smooth and easy though there are a few areas where I must pay attention to the trail. Nearing the Elaterite Butte I change direction and follow the trail to the East crossing the park boundary and then following the rim of Horse Canyon for a short while before arriving to the spectacular view at Maze Overlook. Throughout the drive there are a few minor elevation changes and one or two steep spots, but nothing difficult. A few nice long flat open stretches across the canyon floor break up the drive. Navigation is straightforward, though there are a some sections where it is harder to see the traces of the trail over parts of the rockier terrain.

ABOUT THE CREATION OF CANYONLANDS

The area that became “Canyonlands National Park” in 1964 actually traveled a circuitous path to park status. Though it was first described as scientifically and aesthetically exceptional by the explorers John Strong Newberry and John Wesley Powell, the region remained an anonymous part of the Colorado Plateau until after World War II. The area was known only by a few ranchers, prospectors and scientists who viewed it in utilitarian terms — simply as land that could be used to graze livestock, for oil and gas extraction, or water that could generate power. The aesthetic and ecological value of the landscape was ignored. The idea of a park only came into serious consideration during the 1950s when the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management were trying to find a way to protect the region from grazing and the extractive industry. The NPS proposed to create a recreation area from noncontiguous terrain near landscape select features and after much political back and forth, the park was created, but important geographic areas, including the Maze, were left out. Initial plans for the park included “a wilderness reserve with engineered access corridors that enabled comfortable scenic experiences” — a “Disneyesque” aerial tramway was even considered for the Needles District. Fortunately, changes in thinking about conservation and environmentalism prevented too much modern technological intrusion into the park’s primitive heart. As these new values took root and captured public attention thanks in part to Edward Abbey’s “Desert Solitaire,” wildness became one of the guiding values of the Canyonlands. (For more information on the creation of the park and the policy issues involved, see The Administrative History of Canyonlands)

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 2015 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Moab, UT. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Moab’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 3″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Hard Rock edition with about 6,000 miles on it equipped with BF Goodrich KO2 tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF SOLITUDE

One of the most rewarding aspects of a solo trip in the Maze is experiencing nature in solitude. Being alone forces us to take control of our direction, restores creative energy and teaches fortitude and self-reliance. It also encourages curiosity about the unknown and a longing to explore, which enhance a wilderness experience exponentially. In the past, tribal cultures encouraged the chance for solitude with traditions like “vision quests.” Time away from the tribe was seen as a test of self-sufficiency as well as a time of growth. The individual returned to the group stronger and wiser. Modern technological life has a distinct lack of meaningful “alone time.” Yet the extended seclusion and physical challenge of solo camping in the wilderness can still gives us an unfiltered look at the essentials. All the complicated issues of the world are far off, and the focus is concrete and immediate: walk, drive, eat, sleep and repeat. Consequences of actions are immediately apparent, making life seem much less complicated and the results — a breathtaking view, the thrill of exploration and discovery, the satisfaction of physical exhaustion at the end of a day — are so more vivid and visceral. However, experiencing the awesome power of solitude in the wilderness can also raise some serious mental challenges:

TIME MANAGEMENT: The logistics of camp-craft, travel and navigation consume a surprising amount of time and mental energy when you are traveling alone. To benefit from a solo trip, you need to have enough time so that the expedition logistics become routine, leaving mental space for contemplation and reflection.

DECISION MAKING: There is a sense of freedom in not having to consider the preferences or opinions of others when making decisions on where to go or what to do, however, that means you are solely responsible for the outcomes. There is less room for error on a solo trip than on an accompanied one. And the more difficult and remote the terrain greater the risk. Know your own level of acceptable risk before starting out.

MENTAL STRESS: You may encounter stressful or emergency situations in which you will need to improvise solutions on your own. Your mental skills are more important than your physical skills in these situations. It is important to maintain a positive “can-do” attitude. Be creative, adapt to the situation and learn to work with nature instead of against it.

FATIGUE AND DISCOMFORT: Fatigue is the overuse of the muscles and the mind and is a serious threat. It can cause you to lower your defenses and become less aware and alert to danger. Fatigue and/or the discomfort of extreme temperatures or weather can cause inattention, carelessness, and loss of judgment. Rest, sleep, and a minimum of comfort are essential.

FEAR: The remote nature of the wilderness makes some people worry about getting lost, wild animals, getting hurt or just being uncomfortable. Know how you react to fear and do your best to control it — don’t let your imagination make mountains out of mole hills. Maintain your positive mental attitude.

PANIC: Panic is triggered by the mind and imagination under stress. It results from fear of the unknown, lack of confidence, not knowing what to do next, and a vivid imagination. It can be amplified when alone and cause a person to make a bad situation worse. If you feel yourself starting to panic, stop and regain your composure — whatever it is, it’s only temporary.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

MAINTAINING A WILDERNESS

Two mighty rivers intersect in Canyonlands, and where the Green and Colorado rivers meet, the streams form a gigantic “Y” that defines the national park’s three major administrative districts. (The rivers themselves are acutally a fourth.) Because of the rugged landscape, the sections are not immediately linked by roads. Visitors to the Canyonlands cannot easily go from one district to another, and that may also be by design. The majority of visitors go to the most accessible area of the park to marvel at the high vistas of Island in the Sky. It is easily reached via paved or four-wheel-drive roads from Moab. Less than half visit the Needles District, which is further from Moab. But very few, only about 2% of all visitors, make their way into the Maze District, on the southwest side of that cartographic Y.

HIKING IN THE MAZE

Hiking trails in the Maze are primitive and lead into canyons with varying viewpoints. Access is limited by the nature and depth of the canyons themselves. The main routes into the canyons are cairned from mesa top to canyon bottom, but routes through washes are often unmarked. You should not attempt these hikes unless you are comfortable and experienced with backcountry navigation as many of the canyons look alike and are difficult to identify without a topographic map. The Maze Overlook Trail is the primary access-way down into the labyrinth of canyons, however it does require some basic climbing maneuvers in order to negotiate sections of steep slickrock and pour-offs. A 25-foot length of rope is often essential for raising or lowering packs in difficult spots. Many routes may make hikers with a fear of heights uncomfortable. For more information, see: Hiking and Backpacking in the Maze.

WILDERNESS SKILLS AND SURVIVAL

While enjoying the solitude of the wilderness it is always important to be well-prepared in case something goes wrong. A basic understanding of wilderness survival concepts offers a solid foundation for appreciating the challenges of the outdoors. One of the most important concepts is understanding survival priorities. Alderleaf Wilderness College teaches a simple principle, known as “the Rule of Threes,” that can make the difference between life and death. The Rule of Threes says: You can survive for three hours without maintaining your core body temperature. You can survive for three days without water. You can survive for three weeks without food. This means that the most important survival needs to attend to first are shelter and water. Surviving a difficult wilderness situation also requires meeting many challenges while avoiding panic. Remember the acronymn “SPEAR”: Stop, Plan, Execute, Assess, and Re-evaluate. By systematically assessing, planning, and executing tasks you will help keep your mind and body actively engaged in addressing your situation and maintain an upright attitude. Being able to build or find a shelter is paramount. Key considerations include a location away from hazards and near supplies, some form of insulation from the ground and the elements and a source of heat (body heat or fire-heated). Look first for a possible natural shelter such as a cave or even a hollow stump, or for materials to construct a debris hut or lean-to. Water is the next priority. The best sources for clean drinking water in a wilderness setting are springs, head-water streams, and collecting morning dew (for specific suggestions on finding water in the desert see this Active Times article). If you do not have access to a water purifying filter or treatments, boiling water for 2-3 minutes will kill most bacteria and viruses. After water, fire is probably the next priority. It can help warm your body or your shelter, dry your clothes, boil your water, and cook your food. It also provides psychological support, creating a sense of security and safety. Ideally, when traveling in the wilderness, you should be carrying multiple fire-starting tools, such as a lighter, matches, flint and steel, etc, but even with these implements starting a fire can be challenging in inclement weather. Good fire-making skills are invaluable and knowing how to start a fire by friction could be a life-saver. For more on basic wilderness survival see: Six Basic Survival Skills

NOTE: This is the fourth in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.