A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< BACK: TO MOAB | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO GOLDEN STAIRCASE >

The night had been quite cold, probably in the high 30’s (in Fahrenheit degrees), and I was glad to see the morning sun shining bright. Packing up my gear, I paused to review the maps and the options for the day’s drive. Leaving Keg Knoll, I went west, back to the main road, and then headed south. The drive was easy and the flat desert seemed to go on forever in front of me. The landscape changed from rocky to grassy, and I unexpectedly encountered a cow on the side of the trail. I had seen a lot of tracks along the road, and I hadn’t given them much thought, but when I saw the cow I recalled that this area is part of the “open range,” public land where cattle owners are permitted to let their animals graze.

The first cattle herds were introduced to the area in the 1870s, as the corporate cattle industry spread from Texas to Montana in search of more grazing land. The cattlemen were drawn by the excellent ranges found in the La Sal and Blue mountains, and by 1890 there were tens of thousands of cattle spread over the area. The high plateaus and mountains were perfect summer ranges, but in winter they had to drive the cattle down into the lower elevations of canyon country. The history and folklore of the cowboy era remains in place names, and artifacts like the “cowboy camps” in the national park, but the prominence of cattle ranching in the region diminished greatly after the 1935 Taylor Grazing Act which introduced permits for grazing rights on public lands. The Act was intended to reduce overgrazing which had become endemic, and one of its requirements was that cattlemen who wanted a permit had to own some land of their own in the area. According to the Canyonlands National Park Historic Preservation Team, by 1962 only 683 cows were grazing on national park land.

Though much reduced in scope, cattle ranchers continue to operate in region, maintaining the traditional rhythm of moving the cows down to lower elevations for winter where they have grazing rights on this BLM land. Still, it seemed a bit incongruous to see cows in the middle of what I think of as desert.

The road continued southward, where navigation became a bit more complicated. A series of intersecting trails turned into and then forked off the main road, creating the possibility for confusion. It was a perfect spot to exercise my pathfinding skills. While there was no worry about actually getting “lost,” I needed to pay attention to nuances in order to stay on my plotted route (of course I could always look at the GPS for confirmation, but I wanted to keep it old school). I got out of the Jeep, oriented the paper map to the ground using a compass, and identified the major visible landmarks, noting my exact position. Being able to know my precise location in the middle of the desert without reference to the GPS was a great confidence boost, and I followed the lines I had plotted along the trail the rest of the way until I reached the point where the roads all intersect and head almost due east towards Hans Flat, on the main access route into the Maze District. I enjoyed “playing” with the map and identifying the landscape details as I drove. Somehow it made me feel closer to the environment and more engaged in my surroundings. I was appreciating the desert as I was driving through, not just rushing towards a starting point at the entrance to the park.

The Hans Flat Road, a graded dirt road, is the “major access” route into the Maze District. From the map it looked like it would be quick going on a straight stretch of wide “maintained” dirt road over relatively flat and open terrain. But the reality was 20-something miles of teeth-rattling washboarded bumps that had me slowing to a crawl in some sections for fear of damaging my suspension. It was painfully slow. Tediously slow. Torturously slow. And then there was the unexpected: Mud.

I had been prepared for the contingencies of varied desert terrain including soft sand and rocks, but I hadn’t expected to encounter mud pits out here. It seems the heavy monsoon rains that had fallen several days ago had created some significant obstacles. Stretches of the road were still gauntlets of slippery oozing mud scarred with deep ruts and holes where previous vehicles had gotten stuck. Approaching a particularly nasty looking patch, I got out to assess the situation and air down. I could see on the side of the trail where someone had drove into the bushes to make a completely new “bypass” around the spot. There were several sets of tracks that followed his path. For me, driving off the trail was out of the question, so I needed to look at the worst part of the mud bog towards the middle where the road curved, to make sure there was nothing even worse beyond. Just walking along the side of it I was slipping and sliding, so I put a few loose branches into the bottom of the deepest holes, took a deep breath, walked back to the Jeep, let more air out of the tires and drove through it. A few more mud bogs followed before I finally arrived to the small outpost that is the Hans Flat Ranger Station.

The ranger station is actually at the northwestern boundary of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and serves visitors for northern Glen Canyon as well as The Maze district of Canyonlands. I stopped to check-in and get any briefing information the Rangers might be able to provide. As this was my first visit to this remote section of the park, I wanted to be sure to have accurate information and also to get any and all advice available. The Ranger on duty took the time to walk me through the process of validating my permit and explain a little bit about the specific road conditions of my route. While we were chatting a couple of frequent visitors came in to “check in” and get the latest on road conditions, too. They were headed straight out to the Dollhouse and were glad to hear there were some technical driving challenges on their route this week. Apparently the heavy rains had made some of the roads in the park more challenging than usual. When they learned it was my first time out here and that I was on my own, they graciously offered their CB channel and told me to give them a shout if I had any trouble.

The real potential issue for me would be the weather. Current reports said there would be rain tomorrow and possibly into the next day. The Ranger explained that one segment of the trail I needed to take tomorrow, the Flint Switchbacks, would be extremely dangerous when wet. She looked at my itinerary options, and suggested I camp at nearby North Point rather than go all the way up to High Spur, because it would allow me to get an early start in the morning and get down the switchbacks before the rain started. After having seen the left over mess from the last rains, I was a bit concerned about that scenario too. What if I got down there and there were two days of heavy rain — how would I get back out? She asked me if I had enough food and water for two days extra, and I did, so she said I could just wait it out in place, and it would dry up quickly once the sun came out — reminding me that if I couldn’t get out, no one else could get in, so I could just keep my campsite. We reviewed the satellite radar projection of the storm together, and it seemed like the biggest threat of heavy rains was gone, the mass of precipitation dropped on the other side of the mountains, and the green and yellow band seemed narrow enough now. I felt reassured as I set out for North Point.

Heading to North Point camp, the road goes south along the top of a mesa, occasionally approaching the edge of the rim for dramatic views into the canyons below. The terrain was a familiar kind of rocky and a bit more woodland, and I wondered what the elevation was. I didn’t recall driving up any steep hills but maybe I did because the listed elevation at North Point camp is 6,550 feet (and the elevation of the town of Green River, where I turned on to dirt was 4,078 feet, so I gained about 2,500 feet somewhere).

There was a wild desolate feeling to the landscape as I passed French Spring, where a wildcat oil driller named T.C. Conley built a cabin in the 1920s. Conley was one of many independent explorers lured into the Utah back country by the dream of finding petroleum. Prior to 1890, gold prospectors traveling down the San Juan River in southeastern Utah noticed oil seeps along the river’s steep embankments. Around the same time, two Salt Lake City businessmen found oil dripping from the crevices of rocks along the Green River, and ranchers and other residents of the Uinta Basin came across similar occurrences. Oil and gas prospectors sank approximately twenty-five wells in various parts of the state in the 1890s.

By the 1920s the search for oil was in full swing. One of the most spectacular ventures of the period was a joint project on the Colorado River near Moab. The companies involved in this endeavor included the Utah-Southern Oil Company, the Midwest Enterprises Company, and the Utah Oil Refining Company. Together these three firms drilled a well that hit oil on 8 December 1925. At first the well gushed oil, gas, rock, sand, and gravel hundreds of feet into the air, but very quickly the 84-foot-high wooden derrick caught fire and burned. The well’s promoters were unable to produce any oil from the venture despite their extending the well eventually to a depth of 5,000 feet.

With enthusiasm for the oil industry at a high point, Conley hustled up the venture capital from Continental Oil Company and Texas Oil Company to prospect in the most remote area of the Canyonlands, set up a base near French Spring where there was a reliable source of water and built the road across Horseshoe Canyon to survey and drill.

The Great Depression and the first years of World War II, however, damped many oil men’s enthusiasm for Utah’s petroleum potential, and the operations in the canyonlands area ceased. The Phillips Oil company abandoned the well on the east side of Horseshoe Canyon in 1929. Though it went to a depth of 5,000 feet it never produced in commercial quantities. The traces of the oilmen remain in the artifacts found at the “French Cabin” site (most interesting is an old boiler that was used provide power for Conley’s drilling rig) and the roads that are now our Jeep trails.

My campsite at North Point was on the top of an overlook in a nicely wooded area with some clearing and some shade and I had a postcard perfect view of the Canyons below. All camping here is by permit only, and there are only 20 site/permits spread across the entire area of the Orange Cliffs and Maze District, making for a true wilderness experience. Each site is completely separate and far from any of the others, with a large area designated by discrete markers, allowing visitors to choose their own spot within the landscape. Strict regulations keep the sites pristine and primitive, and from what I could see most visitors are respectful of the leave no trace ethos. The only “down” side to camping within this zone is that wood fires are not permitted.

There were lots of Juniper trees around, and I decided to set up my tent near a large one, then went for a walk around the overlook and wandered down some of the rocks feeling the draw of the canyon below. As the afternoon wore on, the skies got darker, and clouds came in blocking the sun. The specter of a storm was threatening and there was no real sunset.

> CONTINUE: DAY THREE — NORTH POINT TO GOLDEN STAIRCASE

< BACK: TO MOAB | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO GOLDEN STAIRCASE >

WHERE WE ARE

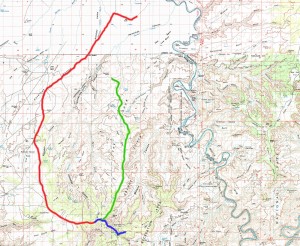

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

KEG KNOLL / HANS FLAT / NORTH POINT – 36 miles – Estimated drive time 3 hours (red and blue routes) OR with optional HIGH SPUR / HORSESHOE CANYON – 58 miles – Estimated drive time 4.5 hours (red and green routes)

Leaving Keg Knoll, I return west to the main road and continue south into an area with some confusing navigation, eventually turning east on the access road into The Maze district to Hans Flat Ranger station. From there I have the option of going a short distance south to my reserved campsite at North Point (blue route), or going north a slightly longer distance via High Spur (green route) and outside the boundaries of the national park, so that I can camp on BLM land with a wood fire. The driving should be relatively easy as these are all maintained dirt roads leading into the park, though there is a section where navigation will be more complex as a web of intersecting trails can make things confusing.

HISTORY: ROUGH COUNTRY FOR COWBOYS

The terrain of the Canyonlands presented some unique challenges to cowboys responsible for the herds. During winter when the cattle were down in the canyons, the cowboys would accompany the animals, moving them around to access food and water, and keeping them from getting lost or trapped in the terrain. Taking care of the cattle was tedious, but the most difficult job of all was getting the herd back out of the canyons in spring. Pushing the cattle up the trail could be dangerous as an account from 1934 illustrates. It had been a very dry year and water was scarce. As the animals were going up the Shaffer Trail, they were becoming tired, foot sore and thirsty. They started balling up in a spot that was only three feet wide, and according to the cowboy, the lead cows, smelling the humid air coming out of the canyon, turned and attempted to go back down the trail. As more animals turned, their horns hooked the cows coming behind them. Frightened cattle attempted to turn quickly on the narrow trail and the cowboy couldn’t get into the congested area to straighten the herd out. Cows began to lose their footing and dropped off the trail tumbling down the hillside. Lodged between rocks or injured and impossible to rescue, 29 cows had to be “put down” during the drive out.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF NAVIGATION

The BLM-administered area of the San Rafael desert outside the boundaries of the Canyonlands national park includes a series of intersecting dirt roads that twist and turn and occasionally dead-end. In addition to the main access roads into the various park units, there are roads left from the area’s mining and cattle raising history that don’t seem to lead to anything precise. While there are some signs to help visitors find the park entrances, many roads remain unmarked. For anyone preparing to explore this remote region, it is imperative to have a solid understanding of maps and land navigation, and to carry a compass in addition to a GPS unit.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

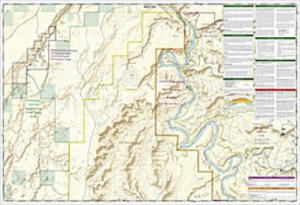

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

NOTE: This is the second in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.