A solo trip into one of the most remote places in the continental U.S., the Maze district of Canyonlands national park, offered some interesting challenges and an amazing experience in the solitude and splendor of the wilder desert landscapes. The route chosen for the six day 450-mile journey was almost completely off pavement (and off grid) apart from the initial and final sections of the loop that started and ended at Moab, UT. The primary goal of the trip was to get an overall introduction to the Maze district and work on preparing for logistical contingencies in remote environments.

< BACK: TO KEG KNOLL | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO MAZE OVERLOOK >

The first morning light spread slowly across the canyon. A layer of clouds blocked the sun, but made for a stunning splash of intense color against the deep vibrant morning blue. Dawn transformed the landscape and it almost looked like a vast ocean rather than a deep canyon, all rendered in the blended tones of a watercolor painting. I packed up camp quickly, trying to get a head start on the forecasted rain. It was critical that I get down the switchbacks before they got wet. Feeling the pressure of a race against time, I moved with purpose, heading south towards Flint Seep.

The road was easy driving apart from a few mud bogs that reminded me to hurry. Though I couldn’t help myself from stopping at an overlook with an incredibly beautiful view of the “Bagpipe Butte” rising up from the bottom of the canyon only a mile from the rim. The top of the massive rock formation looks small from here, yet it is the dominant feature of the skyline from this vantage point. I was learning to orient myself using the rocks as landmarks, just as I would use prominent buildings on a city street.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was actually on top of the Orange Cliffs, driving along the very edge. The Orange Cliffs are a line of shear rock walls running roughly north-south along the west side of the Canyonlands. They are Wingate sandstone, the same material that forms the prominent red cliffs and spires within the Canyonlands basin. Wingate sandstone frequently appears just below the Kayenta Formation and Navajo Sandstone. Together, these three formations often result in immense vertical cliffs of 2000 feet (609 meters) or more. Remnants of wind-born sand dunes deposited approximately 200 million years ago in the Late Triassic period, Wingate layers are typically pale orange to red in color.

The elevation here varies from approximately 3,700 to 7,000 feet above sea level, and the Flint Trail overlook is at 6,850 feet. Down below a vast landscape of colorful buttes, mesas, canyons, and cliffs rolls on until infinity.

The sky was still a flat grey when I arrived at the Flint Trail Overlook, but the rain hadn’t started. The only way to drive from the top of the Orange Cliffs down into the Maze is to descend this series of steep, rocky switchbacks. Before the Canyonlands National Park made this into a protected area, the Flint Trail existed as a cow path used by cattle ranchers to gain access to the pastures below. Local cowboys used to call this area of canyons “Under the Ledge.” The trail was improved enough for 4WD use in the early 1950s by uranium prospectors. From the overlook I can see the ribbon of trail making its way down the cliffs and continuing off into the canyons beyond.

I pulled over to the side and shut the engine off. The Ranger had told me that it was important to stop here, get out of the Jeep, and watch and listen for about fifteen minutes to make sure there was not another vehicle coming up. The switchbacks are so narrow that two vehicles cannot pass, and they are too long and steep to want to have to back up out. It was a beautiful place to just sit and observe. Apparently, this area was once covered with flakes of flint–the artifacts of the Anasazi Indians who chipped arrow points and other stone tools on the site centuries ago–but their trace is gone.

The trail drops 800 feet in elevation over less than a mile, and it looked quite intimidating in its entirety. Though I could see the top of the switchbacks, there are sections that remain hidden from view, which is probably why it is important to observe for a while. It was still and quiet, and I heard no motors. After more than fifteen minutes I still hadn’t seen any motion or the flash of light reflect off a windshield, so I concluded it was safe to go ahead down. From the edge of the ledge, the trail below looked steep and rocky, but solid, and I began the slow controlled descent, glad to be in the Rubicon, which seemed to stick like glue to the terrain in 4-Lo first gear. I was thankful there was no mud, and could see why this would be perilous if it were wet.

I relaxed, appreciating the spectacular view as I eased myself down towards the canyon bottom. The trail was wide enough to feel comfortable even if it wasn’t wide enough for two vehicles. The first turn is a strange combination of tight turn with a simultaneous steep descent that feels a bit odd, but the dirt is packed and at no point does it seem like I might slip. The Ranger had mentioned that many vehicles will have to start the turn then back up slightly and reposition to complete it. That reminded me of the origins of the term “switchback” which referred to the point on a mountain railway where trains reverse direction to continue up or down a slope without turning.

After the first hairpin turn, the trail continues winding down, in between and around the rocks, hugging the wall of the cliff, and does get quite narrow at a few points. The second “leg” gets steeper tighter and rockier than the first part, but the drive was not at all difficult. I took my time, stopping often for photo opportunities, walking down and back up some sections to get different views of the landscape below. A little squirrel watched me quizzically from beneath a bush on the side of the ledge. Apart from him, I had the trail to myself so early in the morning.

The rest of the switchback section was less intimidating, and toward the bottom it began to flatten out as it approached Flint Cove. I made it to the base of the cliffs, then turned around to photograph the switchbacks from below, but realized that one cannot really see them from this angle because the trail is hidden from view by the rock. I suddenly understood why it was so important for the person on top of the cliffs to verify that no one is coming up before starting down.

FOR MORE DETAILS SEE: IN FOCUS: DESCENDING THE FLINT SWITCHBACKS

The terrain on the floor of the canyon was different than that at the top. It almost seemed like ashes or soft gravel. It was not the same white stuff that I encountered in the desert the other day, but something different yet again. The cement-like earth seemed to transition right into the red rock behind it. I was feeling a visual drama of textures and contrast of materials and lines and absence of color, but color all the same. I finally decided that the cracked grey earth looked like “petrified snow.” I paused to explore for a while before continuing towards camp.

Heading north-east I was soon back on the familiar terrain of juniper bushes and red rock. The trail was sandy here and my thoughts began to turn to the impending rain. The sky had not cleared, and if anything the cloud cover was thicker and darker. I could no longer even see the orb of the sun. If it rained hard or long this could become pretty muddy. But at least I had passed the dangerous section of the trail, so rain at this point would just be a “minor inconvenience.” Still, I decided it would be smart to make sure I didn’t put my tent in a low spot. It would not be fun to wake up in a small lake.

The Golden Staircase campsite was in a beautiful and wild location and I set my tent up in between some junipers and rocks before going for a walk. I was no longer in any hurry and started wandering randomly around behind my site. I walked over some rocks, and down a few more, and then right up to the edge of another ledge. I had thought I was on the canyon floor, but I now realized there was another canyon below me. Or perhaps, more accurately another “set” of canyons. I was somewhere in the middle.

Walking along the ledge, I was looking across and down onto a landscape that seemed like another planet. A labyrinth of strange terrain shapes that form canyons from which otherworldly rock sculptures rise and meld into one another again sprawling out all the way to the distant cliffs marking the horizon. This is the “Land of the Standing Rocks” and it fascinated me as I tried to distinguish some kind of landmark or a way of telling one section of rocks from another, but it truly does seem like an insane maze — a warped stone version of a sea of dunes that all look the same.

The tableau before me was really a collage of geology crafted by millions of years of erosion. Interestingly, most of the rock found in Canyonlands actually came from distant mountain ranges like the ancestral Rockies and even the Appalachians. For millions of years that rock was broken down and carried here by wind and water, creating deposits that eventually became distinct layers of sedimentary rock — something like a geologic layer cake, with most of the material hidden below the surface. Then, about 20 million years ago movement in the Earth’s crust began to alter the landscape creating what is know as an “Uplift” that raised the area of the Colorado Plateau as much as 10,000 feet in some places. The movements also created cracks where melted rock rose from deep inside the Earth. In some places, it cooled before reaching the surface, creating pockets of harder, igneous rock within the surrounding sedimentary layers. Eventually, erosion exposed these harder deposits, creating the the La Sal, Henry and Abajo mountain ranges. Rivers that once deposited sediment on the lowlands began to remove it from the emerging plateau exposing buried sediments and carving canyons. As softer rock erroded away, layers of harder rock form exposed shelves, giving the canyon walls their stair-step appearance. Occasionally, a slab of harder rock would protect a weaker layer under it, creating balanced rocks and towers like those in the Land of Standing Rocks which are remnants of a thick strata of rock called the Organ Shale Formation.

I was starting to understand that this whole Maze area was like an endless series of canyons within canyons. I had been on the ledge above here yesterday, and now I was on this middle level, and I wondered at times if some of the old explorers thought maybe they would find a “bottom” if they kept on going down into the next lower level canyon, and was it really endless or is there a bottom somewhere (it was easy to get philosophical, or metaphysical, or whatever, out in this vastness). Looking across the landscape, I felt as if some kind of optical illusion was making it impossible to tell what was flat, and what was steep and what was really bigger or further or closer. But perhaps it was just the lack of sun and shadow that normally help define the relief.

I was following an actual “trail” very discretely marked with cairns, but because of the nature of the terrain, it was not such an “obvious” hiking trail in the way I am used to. There were a lot of spots to scramble over rocks and things and in a few places I had to give the path some thought, though it wasn’t physically “hard” or “strenuous.” It was a little bit like pathfinding, because at first glance everything looked quite wild and natural. The fact that it was mostly flat stone meant there were no clear footprints or flattened earth or a cut “trail.” I was learning to look at the landscape and see where there seemed to be a “path” in terms of an opening or easier way to go. I remembered an orienteering coach explaining how the best way to find the “route” where there is not really a “trail” was to look for the easiest way to walk, because people naturally take the easiest way, disturbing rocks and impeding the growth of plants (at least in the desert), creating a slightly cleared path. When you look at the overall terrain from a slight distance you can see the “line” of the path. And out here whenever I did that I would see the discretely placed cairn marking the way.

This path was originally used by sheep and cattle ranchers to move their animals between “Ernie’s Country” and the Elaterite Basin. At the spot known as “China Neck” the mesa narrows to a thin neck of stone just ten feet wide. It is almost like someone built a bridge here, but it is natural and continues for roughly 150 feet to the top of the ridge on the other side. The bridge is a monolithic piece of white sandstone in the middle of a mesa that is crumbly brown-red shale, making it seem out of place. The cowboys thought it resembled porcelain, hence the name “China Neck.” Crossing it, I paused in the middle to just appreciate the dizzying views on either side. It felt empowering to be out here on my own, alone in this wild place, on top of the world.

I continued down the trail for a while, just enjoying the afternoon walk despite the lack of sun, though the threat of rain and what it could mean for tomorrow’s journey remained in the back of my head. The hiking trail goes all the way down and across to join the Jeep trail to the Dollhouse on the other side, but I turned and headed back up to my campsite. The stormy sky made dramatic light, creating an ephemeral moment of desert beauty that signaled the threat from the coming harsh weather. As I returned to camp I could smell the junipers. These hearty plants thrive in some of the most inhospitable landscapes imaginable. They can withstand baking heat, bone-chilling cold, intense sunlight, little water and fierce winds. Sometimes they appear to grow straight out of solid rock. Together with the pinyon pine, they are the most prevalent plant on the Colorado Plateau, and the ecosystem at this elevation between 4,500 and 7,000 feet above sea level is referred to as “pinyon-juniper woodland.” They were plentiful around my campsite and offered protection against the wind. I hurried to start my charcoal fire in the little fire pan before it got fully dark. While it was not as beautiful as a wood fire, it did keep me warm as long as I sat close enough to it once the embers got hot.

> CONTINUE: DAY FOUR — GOLDEN STAIRCASE TO MAZE OVERLOOK

< BACK: TO KEG KNOLL | THE MAZE REPORT HOME | AHEAD: TO MAZE OVERLOOK >

WHERE WE ARE

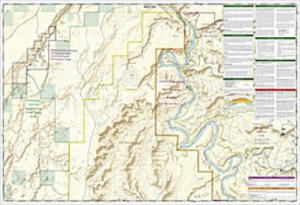

The Maze is one of three distinct districts of the Canyonlands national park, located near Moab, Utah. This journey loops north of the town of Moab, then west to Green River and south into the San Rafael desert to reach the Maze district of the park, continuing south into the Glen Canyon Recreation area and then east to Blanding and back north to close the loop.

THE COMPLETE JOURNEY

The Maze Report Home

Gallery: Into the Maze

Day One: Moab to Keg Knoll

Day Two: Keg Knoll to North Point

Day Three: North Point to Golden Staircase

Day Four: Golden Staircase to Maze Overlook

Day Five: Maze Overlook to Hite Crossing

Day Six: Hite Crossing to Moab

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

NORTH POINT / GOLDEN STAIRCASE – 15.5 miles – Estimated drive time 1.5 hours

(click map for larger view of route)

From North Point camp I return to the main road headed south to the start of the Flint Trail switchbacks. Then go down the switchbacks to the canyon floor at Flint Cove taking the trail north east to the Golden Staircase. The highlight of the trail, the switchbacks, makes a steep descent over rocky terrain that can be quite impressive. It is only wide enough for one vehicle, so it is critical to make sure no one is coming up before going down. The switchbacks can be dangerous after rain. After the switchbacks there is a section of grey earth that can become claylike when wet that might also pose a problem. Beyond that the rest of the trail is dirt and rock, but nothing difficult.

ABOUT THE MAZE

The Maze is the most remote district of Canyonlands, attracting self-reliant visitors in search of solitude amidst the red rock wilderness. This area ranks as one of the most remote and inaccessible regions in the country. Four-wheel-drive roads and foot trails lead to the Land of Standing Rocks, the Doll House and the Maze Overlook. The Maze itself, described as a “thirty square mile puzzle in sandstone,” is a complex jumble of canyons that can be reached only on foot. Because of the distances involved in reaching the district and the difficulty of roads and trails, travel to the Maze requires a greater degree of self-sufficiency. Rarely do visitors spend less than two or three days in the Maze, and the area can easily absorb a week-long trip. According the National Parks Service, visitors should be skilled in the use of map and compass and in technical four-wheel driving. The Maze and Orange Cliffs contain roughly 19 miles of established trails and about 130 miles of four-wheel-drive roads. Hiking in the Maze is strenuous but rewarding. Primitive trails lead into the Maze and to other geological features, as well as to views of the rivers. There are no signs and routes are cairned lightly or not at all. If you are following a cairned route, do not count on finding cairns in the washes. Many of the canyons look similar and are difficult to identify without a topographic map. Descending into the Maze requires a 4WD vehicle and drivers must traverse slopes of bentonite clay that are extremely slippery when wet. The route should not be attempted in poor conditions. The jeep trails may be impassible after bad weather, and the section from Teapot Canyon into the Land of Standing Rocks is considered very difficult under any conditions. The NPS reminds visitors that there is considerable risk of vehicle damage, and drivers in the Maze should be prepared to make basic vehicle repairs and be able to self-recover should they get stuck. It is recommended to bring one or two full-size spare tires, extra gas, extra water, a shovel, and a high-lift jack. Visitors should also note that a portable toilet system is required for all overnight stays.

ABOUT THE JEEP

This journey was made in a 2015 4-door Jeep Wrangler Rubicon sourced from Barlow Adventures in Moab, UT. Traveling alone in such a remote area made vehicle capability and reliability top priority. Barlow’s Jeeps are professionally modified specifically for Moab’s adventurous trails and back roads, with 3″ suspension lifts, 33″ heavy-duty off road tires and extra undercarriage armor. The company has an outstanding reputation within the off-road community for the quality and condition of its Jeeps as well as for the general support provided. The specific Jeep used for this trip was a Hard Rock edition with about 6,000 miles on it equipped with BF Goodrich KO2 tires and in top condition. There would be no worry about mechanical breakdown and the Jeep was more than capable of facing any of the terrain challenges expected on this route.

SPOTLIGHT: THE CHALLENGE OF WEATHER

Backcountry driving conditions can change rapidly due to weather events, making a multi-day journey into remote areas without communications a real challenge. In addition to preparing for the expected seasonal weather conditions, it is important to have contingency plans in case roads become impassable or extreme weather threatens survival. Before setting out, become familiar with the typical temperature range for the period, as well as the historical lows and highs. Make sure to consider those record lows/highs when selecting appropriate gear. This is especially critical in “shoulder” seasons where weather can vary greatly. Sleeping bags should be rated for the lowest temperature, not the average. And always bring along one or two emergency survival blankets for each person. Start tracking the weather prior to departure, and check the latest forecast again as you begin your journey. Be prepared with alternate routing and enough food, water and gas to “wait it out” if unexpected weather blocks you in place. Always check with ranger stations or visitor centers for the latest road conditions and a weather update. They will often have more precise forecasts for the specific areas of travel and will be familiar with local weather patterns and “sensitive” areas of the route that tend to become troublesome under certain conditions. Monitor the skies, look for “safe” ground, and have a plan before bad weather comes in. Canyonlands national park is in a “high desert” region that experiences wide temperature fluctuations, sometimes over 40 degrees in a single day. During the temperate seasons (April through May and mid-September through October) daytime highs average 60- to 80-degrees Fahrenheit and lows average 30- to 50-degrees. Summer is characterized by temperatures in excess of 100-degrees Fahrenheit and violent storm cells known as “monsoons” which often cause flash floods. Winters are cold, with highs averaging 30- to 50-degrees Fahrenheit and lows averaging 0- to 20-degrees and even small amounts of snow or ice can make local trails and roads impassable.

SUGGESTED MAPS

USGS 1:100,000 topographical maps were used for general routing and orientation, as they provided the best overview of the journey and include the prominent distant terrain features that define the landscape. The journey spans five sector maps (links download full resolution maps from USGS store):

Moab – 1:100,000 topographical map

San Rafael Desert = 1:100,000 topographical map

Hanksville – 1:100,000 topographical map

Hitecrossing – 1:100,000 topographical map

La Sal – 1:100,000 topographical map

For more detail, National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps were used. These printed maps come on reinforced water-proof and tear-resistant material, and include detailed information on recreational trails and points of interest. There are several maps that cover areas included in this journey, though the most critical are the Maze and Canyonlands maps. An important note: be aware that the Maze district map DOES NOT show the Hans Flats Ranger station or the exit to Hite Crossing.

Canyonlands National Park – (210) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 Topographic Map

Maze District: Canyonlands National Park – (312) Trails Illustrated 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab North – (500) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

Moab South – (501) Trails Illustrated 1:70,000 & 1:35,000 Topographic Map

San Rafael Swell – (712) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area – (213) Trails Illustrated 1:90,000 Topographic Map

CURRENT MOAB WEATHER

ENVIRONMENT: THE HIGH DESERT

With a mean elevation of around 3,000 feet and peaks over 12,000 feet above sea level, the Colorado Plateau is at the the heart of what is known as “high desert.” High deserts are simply inland high-elevation (commonly 2,000 feet or more above sea level) deserts. The Colorado Plateau is in the interior of a large continent, far away from significant water sources. It is also known as a “cold desert” because even though low humidity allows greater penetration of solar radiation, winter air temperatures frequently drop below freezing. In turn, summertime air and especially ground temperatures can reach levels lethal for many organisms. After sunset, the ground rapidly loses heat to the night sky and ambient air temperatures may drop significantly before dawn. Temperature fluctuations of over 40 degrees in a 24-hour period are not uncommon. It is a different environment from the Sahara-like sandy terrain we typically think of when we hear the word “desert.” A “desert” can form anywhere lack of water limits biotic productivity. Water may exist in an unusable form such as ice, or may be absent altogether.

NATURE: THE UTAH JUNIPER

The Utah juniper, so prevalent around the Canylonlands, can withstand drought conditions that often kill other plants. It has a massive underground root system that accounts for as much as two-thirds of a tree’s total mass, enabling it to penetrate 25 feet straight down in search of water. The trees grow very slowly, and a five-foot tall juniper may be 50 years old. They have an average lifespan of between 350 and 700 years, with some even passing the millennium mark. The individual trees are visually unique, and it seems no two look alike — some are bushy, some have multiple trunks, and many have poorly-formed crowns that are a mixture of live and dead branches. To conserve water junipers can self-prune, stopping the nutrient supply to one branch in order to ensure the survival of the tree. Juniper berries are pea-sized and light blue. The “berry” is actually a tiny pinecone covered with a drought-resistant waxy coating. Though not as popular as pinyon pine nuts, juniper berries are a staple for jackrabbits, coyotes and a variety of birds. The ancestral Puebloans used the plants’ medicinal qualities to treat stomach aches, coughs and headaches. The dried seeds were used for beading necklaces and as the “rattle” in rattles, and juniper logs were used to build ceremonial hogans and other structures. Today juniper remains a favorite firewood, but they are protected in the national park, where in any case, wood fires are not permitted, and their oddly twisted trunks, with branches pointing in all directions, can be appreciated for their mystical quality against a stark contrast of lifeless rock that surrounds them. (For more details see The Indomitable Juniper)

HISTORY: THE FIRST JEEP TOURS

The first commercial Jeep tours in the area began in 1953 before the park was created. A local resident named Kent Frost started taking visitors into the Canylonlands basin to show them the surrealistic natural beauty of the area while supplementing his family income. Back then his clients were not typical tourists, but rather people who liked to go out camping in rugged country and explore. According to an interview conducted with Frost in 1994, he made the first Jeep trip into the Maze not long after the bulldozers cut the trails. He and his wife had explored the area a bit and had always wanted to go over toward the Doll House, so once a primitive road had been cleared he prepared for a Jeep trip and invited Randall Henderson, the publisher of Desert Magazine to come along. It was 1957 when they drove as far as they could with the Jeeps along an old horse trail and figured out a route in there. After that he began running regular commercial trips to the Standing Rock country. The tour was usually a 6-day camping trip on a loop around varied terrain for people interested in getting out and discovering places that others hadn’t seen before. Frost established most of the routes that would become the “official” trails once the park took control of The Maze district. (For more details see the Interview with Kent Frost)

SCIENCE: READING THE CLOUDS

Getting accurate weather information for remote wilderness locations is not as easy as going to weather.com, because searching for weather in a nearby zip code will not necessarily give you results for the backcountry which may have a very different elevation. A better tool is this National Weather Service site which has a feature that lets you search by clicking on a large map then zooming in on a topo map or by entering GPS coordinates. You can also get a sense of the trajectory of major weather systems by accessing the current satellite radar imagery. In the United States weather patterns generally move west to east. Look west of your destination by 300-500 miles for a good idea at what’s coming in the next 24 hours. Once you are out in the wilderness, you should keep an eye on the sky. Changes in weather can usually be anticipated by observing the shapes and movements of the clouds.

Warm fronts progress from thin, high-level cirrus clouds to low, dense stratus clouds. A warm front moves at roughly half the speed of a cold front and rarely produces violent weather. However the precipitation associated with a warm from may continue longer. The cirrus clouds may precede the front by as much as 48 hours. These thin wispy clouds can resemble white brush strokes on a blue canvas high in the sky. Cirrocumulus clouds arrive next, often appearing as small puffs or rippled rows, followed by cirrostratus clouds, which tend to wallpaper large areas of blue sky with thin, bright sheets of clouds. Filled with ice crystals, cirrostratus clouds frequently cause a halo to form around the sun. Both cloud types float high in the sky. The precipitation finally arrives with altostratus (dense, smoky looking, mid-level) and nimbostratus (gray, thick, low-level) clouds bringing anything from a drizzle to a steady rain or snow.

Cold fronts involve cold air masses that wedge under warmer air pockets. A cold front can develop rapidly and move swiftly, causing temperatures to drop, wind directions to shift and barometric pressure to fall. Cumulus clouds are white, puffy, fair-weather clouds, but if they continue to build upward, rain may come late in the day. The Cumulonimbus clouds rise vertically and expand dramatically from those original white, puffy bases to soar high into the upper atmosphere. On other occasions their tops will flatten out into a menacing, anvil-like shape. These classic “thunderhead” clouds foretell potentially severe weather. Cumulonimbus clouds also form independent of cold fronts, blossoming in the afternoon hours of very warm days and producing late-afternoon thunderstorms. (For more information and a great guide see How to Forecast the Weather with Clouds)

NOTE: This is the third in a series of segments highlighting details of a solo Jeep trip into The Maze district of Canyonlands national park, in Moab, UT. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in October 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads. For more information about the specifics contact us.