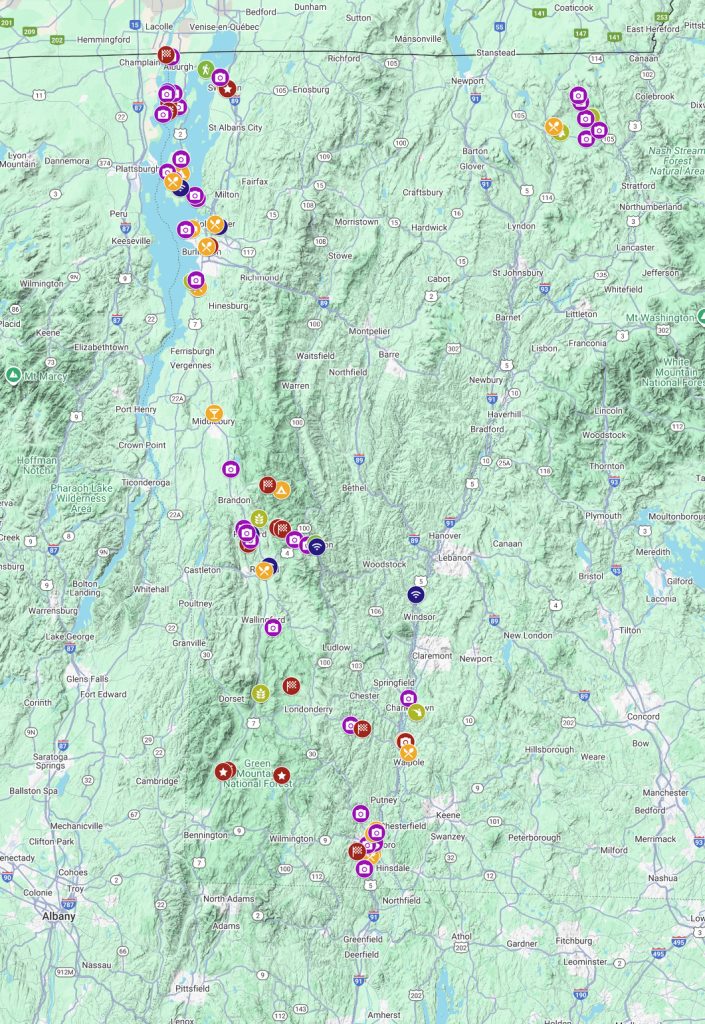

Last night I studied my maps and the iNaturalist app to try to identify a promising location for beaver scouting in the Colchester area. I had heard that there was beaver activity near the mouth of the Winooski River, but zeroing in on the exact part of the river where the beavers had been sighted was not an easy task. Looking at the app I could see clusters of sightings and sign reported relatively recently, but getting near enough to the locations to have a clear view of the river would prove challenging. The main problem is “private property” — that is to say that almost all access to the river banks is “blocked” by privately owned land. There are a few public access points to the river itself, but without a watercraft of some sort there wasn’t any obvious way to reach the area where the beavers had been sighted. Of course that wouldn’t stop me from trying to get as close as I could, and from my study of the maps I noted that there was public lands along a section of the river delta.

While it seemed unlikely that the beavers would go out into the open waters of Lake Champlain, a strip of public land known as Delta Park looked like it wound around the mouth of the Winooski River. It might be thickly wooded and impassable but it was my best chance for access and so I decided to head out there before sunrise. My first stop was the public boat launch not far from one of the iNaturalist beaver sighting clusters. But as I feared, the woodlands went right up to the riverbank and there were no footpaths or obvious “trails” through the thick brush. The Winooski river bends in a twisting series of s-curves as it makes its way into the lake, and it was just impossible to see very far in either direction from the boat ramp. There were no obvious signs of beaver presence that I could see, so I got back in the Jeep to look for the Delta Park.

I found the small parking area for the Delta Park not far from the boat ramp. There was a hiking trail through the woods, and while I was unsure where it led, I decided to give it a try. It turned out to be a very short path that led out to reveal a wide open “beach” of sorts. It looked like a “tidal basin” to me, but I don’t think lakes have tides — it was a flat empty sandy stretch with puddles of water and debris that included many downed trees, their roots in various stages of becoming “driftwood” and the whole scene was transformed by a diffused morning light as the sun came up behind the cover of low clouds. It was absolutely beautiful in its own way and I momentarily forgot all about the beavers as I let myself be enchanted by the magic of the moment. I wandered the “beach” delighting in discoveries of driftwood and footprints and the randomness of nature’s “art”. I started walking towards the water’s edge and following it back in the direction of the river.

From here it was hard to tell where the river ended and the lake began and even the earth under my feet seemed to be in transition, solid in one spot and soft sinking mud in the next, as if it couldn’t decide if it wanted to be dry land or under water. I guess this is what a delta is, a transition zone between the water and the land. From all the downed trees it also seemed a bit like nature’s dumping ground. I don’t know where the trees came from or how they fell or why they ended up here, but it was strangely beautiful in a desolate way and I was just appreciating the ephemeral nature of the scene as the morning light continued to transform the colors and textures of everything around me.

I had almost walked all the way back to the Winooski River Iron Bridge when I noticed a few other early morning photographers who were obviously serious birders with tripod mounted spotting scopes in addition to their big cameras. They looked like they were very familiar with the area, and as they were just walking along the edge of the brush line, I figured I wouldn’t be disturbing them if I asked a question. As I approached the first man he seemed friendly enough and when I asked if he knew of anyplace nearby where he had maybe noticed beaver activity or sign, he thought about it for a bit before answering “no”. He didn’t think there were beavers around here. I explained the location of the sighting clusters from iNaturalist and how they were just a little ways down the river from where we were standing, but he shook his head, then suggested I ask his friend who had more knowledge of the area than he himself. I thanked him and walked towards his friend to repeat my query. The second man agreed that there were not likely to be any beavers here. Then he continued on to say he had seen them often at another location on the Shelburne Bay. He gave me directions to the precise location where he saw them, and it turned out that it was not far from where I was planning to go later in the afternoon. I thanked him and headed back across the delta to find my Jeep and continue my day. It was too late for beavers to be still be out now, but I would check out the Shelburne Bay location in the late afternoon, when they might start to come out again.

Shelburne is just south of Burlington, and is the “home” of the Shelburne Farms, a National Historic Landmark on the shores of Lake Champlain. It was developed in the late 19th century using money inherited from railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt to purchase a large number of individual agricultural properties which the family hoped to transform into a model agricultural estate. The family commissioned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, of Central Park fame, to guide the layout of 3,800 acres of farm, field and forest, and New York architect Robert Henderson Robertson, to design the buildings. The property is nationally significant as a well-preserved example of a Gilded Age “ornamental farm,” but I am going there to learn about dairy farming and cheddar cheese. In the 1980’s the farm became a non-profit educational resource that focuses on promoting environmentally, economically and culturally sustainable rural land use. Gardens and pastures were repurposed to create classrooms for learning and the nonprofit helped to establish the area’s first community gardens and the Burlington Farmers Market. The farm’s grass-based dairy supports a herd of 125 purebred, registered Brown Swiss cows and their milk is made into farmhouse cheddar cheese. Visitors are welcome learn more about connecting to–-and caring for–-the earth through a series of workshops, events and educational programs.

When I arrived for the cheesemaking program, I had expected to visit a “typical” Vermont farm, but soon realized what “estate” meant. The property was vast, and more like a historical “park” than a normal farm — Olmsted’s purposeful design of the space definitely made me think more “central park” than “rural farm”. But the animals grazing in one of the fields made it clear that this was indeed a “working farm,” and as we headed to the dairy where the cheese is actually produced, one of the farm’s interpretive guides explained the history of the land itself.

The land that is now Shelburne Farms was covered by a glacier a mile thick about two million years ago and as it receded, an enormous lake submerged the area. The lake then became a shallower brackish sea with streams and rivers cutting deep channels through the rock. By 8,000 BC, Paleoindians were using the waterways and settling seasonally as they followed the migrations of herd animals. As new agricultural tools and techniques developed Native Americans created more permanent settlements and when the first Europeans arrived they encountered the Abenaki who were living in seasonal villages alongside the waterways. The Town of Shelburne was chartered in 1773, and the Europeans built mills and cut forests for farmland devoted to sheep, and other crops. By mid-1800’s, Shelburne had over 1,000 residents and over 17,000 sheep on the land. But as railroads and settlers moved west, cheap western wool compelled many Shelburne farmers to diversify into dairy farming and orchards. The railroads driving this shift made the Vanderbilt family fortune, which would soon underwrite the creation of Shelburne Farms.

Vermont is known for it’s cheddar cheeses and Shelburne Farms began making an artisanal cheddar. Nearly every day since 1980, their cheesemakers turn fresh milk into raw milk cheddar using just four ingredients: the milk from a pasture-raised herd of Brown Swiss cows, starter culture, rennet, and salt. It’s a physical, hands-on process that requires careful attention to every detail and step. The cows’ pasture-based diet shifts seasonally, and the cheesemakers respond to slight changes in the milk by precisely measuring and adjusting for acidity, moisture, and salt content to craft a consistently delicious product that truly reflects the land it comes from. Shelburne Farms crafts about 170,000 pounds of cheddar a year.

I could see the cows on top of a distant hill as they began to wind their way in a long line towards the dairy for their daily “milking”. A low rumble of moo-ing accompanied the slow motion of the line as they reached the barn and made their way to the milking stalls — a familiar daily routine. The cows seemed happy enough and “happy cows make good cheese”. The cheesemakers would craft that milk into different versions of cheddar producing a variety of flavors based on aging and other factors. I tasted a few different varieties and purchased some “for the road” before leaving the property as the afternoon light was just beginning to turn golden.

It was a good time of day to begin scouting for beaver activity and so I headed towards Shelburne Bay, looking for the location the birder had described. It wasn’t far from the farm, and as I reached the parking area for the boat launch the sun was beginning to get a little bit lower in the sky, though there was still more than an hour until sunset. I took a quick walk around the boat launch which led into the bay, but on the other side of a small bridge was a slow moving creek that looked more likely to be “beaver territory”. I could see that there was a walking trail, just as the birder had mentioned, and a sign said it was the LaPlatte River Marsh Natural Area, so I decided to check it out. The trail was a little bit overgrown and there were wooden planks stretched out over heavily rutted dried mud. I imagined it might actually be wet if it weren’t for the drought (and I was actually glad it was dry because my balance isn’t great, and I didn’t have my boots on). I followed the path a little ways until I came upon a random bench placed on a steep bank overlooking the stream. It was the first spot where there was a clearing with a view down to the water and I wanted to see if I could see any indication of beaver presence. I could only see a small section of the stream, and there were no lodges or dams within sight, but for some reason I decided to just stop and sit on the bench for a few minutes, just observing the water. It was a beautiful afternoon and I was trying to figure out how far along the trail I should go and if I should wait until after sunset when I might have a better chance of actually seeing a beaver, but I was also concerned about trying to make my way back across the narrow boards (some of which were quite rotted and seemed like they might break under my weight) in the dark. I hadn’t brought my hiking stick or my headlamp, as I thought it would be a quick in-and-out walk, but now I had to make a decision.

As I pondered the options, I noticed some movement in my periphery, and I thought it might just be reflections on the slow moving water. I turned to look more closely, and it seemed like something was floating towards my location, but it was too far away to make out what it was. I could see some plant matter, and thought it might be loose weeds. I picked up my camera and zoomed the lens to maximum, using it like a spotting scope to see if I could make out the distant form. Even with the 600mm lens, it was hard to tell, but I definitely saw the ripples of motion. Maybe a duck, though it was very low in the water and all alone. I tried to focus more clearly but it was moving in and out of the shadows. As it came a little closer I could see a form that made my heart skip a beat. Could it be? It was too early yet for beavers to be out, but maybe? I fired off a few frames just in case, and as it approached the clearing I was sure it was a beaver even though it was low in the water, almost like an alligator, and dragging some kind of plant behind it. I wanted to watch where it went to see if I could see a lodge or dam, but when it was almost directly opposite me, it dove down and disappeared, seemingly into the river bank itself (I would later learn that this was a “bank lodge”).

I was thrilled that I had finally gotten to see a beaver in it’s natural environment, even if it was only for a few moments. I waited on the bench to see if it was going to come back out, but I also know that beaver lodges have multiple entrances and exits and if the beaver had noticed me, maybe it was going to use a different exit to hide its movements. The stream was quiet now and after a while I determined that the beaver was not going to come back out in the open any time soon. Still I was very happy with my photo, and just getting to observe the beaver for a few moments was a treat. I made my way back out towards the boat ramp and my Jeep and happily called it a very successful day.

ABOUT THE JOURNEY

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads.org, set off on a fun overlanding adventure exploring around the state of Vermont for a few weeks in September. Driving and camping out of her 2019 JL Rubicon, she was able to check out several different regions and enjoy some local cultural and historic sites while en route to “Beaver Camp” at the Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center in Brattleboro. The 2nd Annual “Beaver Camp” is a workshop event dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts with workable solutions that allow the beavers to continue their important role as a keystone species restoring and conserving wetland ecosystems.

WHERE WE ARE

Vermont is part of the “New England” region of the United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. The geography of the state is marked by the Green Mountains, which run north–south up the middle of the state, separating Lake Champlain and other valley terrain on the west from the Connecticut River Valley that defines much of its eastern border. A majority of its terrain is forested with hardwoods and conifers. The Algonquian-speaking Abenaki and Iroquoian-speaking Mohawk were active in the area at the time of European encounter, but the history of the indigenous peoples here goes back about 12,000 years. The first humans to inhabit what is now Vermont arrived as the glaciers of the last ice age receded. Small groups of hunter-gatherers followed herds of caribou, elk, and mastodon through the grasslands of the Champlain Valley. At that time much of region was mixed tundra. The oldest human artifacts are 11,000 year old projectile points found along the eastern shore of the saltwater Champlain Sea. This time is known as the Paleo-Indian period. By about 8,000 years ago, the Champlain Sea had become the freshwater Lake Champlain and the climate was more temperate, bringing increased diversity of flora and fauna. By about 4,300 years ago, the forests were as they are today. Large mammals underwent extinction or migrated north, and the human population became reliant on smaller game and plants. Most of the state’s territory was occupied by the Abenaki, south-western parts were inhabited by the Mohicans and south-eastern borderlands by the Pocumtuc and the Pennacook. In 1609, Samuel de Champlain led the first European expedition to Lake Champlain. He named the lake after himself and made the first known map of the area. The French maintained a military presence around Lake Champlain, since it was an important waterway, but they did very little colonization. In 1666, they built Fort Sainte Anne on Isle La Motte to defend Canada from the Iroquois. It was abandoned by 1670. The English also made unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area in the 1600s. In 1724, they built Fort Dummer near what is now Brattleboro, but it remained a small and isolated outpost, often under attack by the Abenaki. Vermont became the 14th state of the United States on March 4, 1791. From north to south, Vermont is 159 miles long. Its greatest width, from east to west, is 89 miles at the Canada–U.S. border; the narrowest width is 37 miles near the Massachusetts border. There are fifteen U.S. federal border crossings between Vermont and Canada. Several mountains have timberlines with delicate year-round alpine ecosystems. The state has warm, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. The topography and climate make sections of Vermont subject to large-scale flooding, and extreme rain and flooding events are expected to intensify with climate change.