I was still looking for a good place from which to catch the sunrise this morning and had heard that it might be good to go up to a place called “Mountain Top” which is some kind of resort-hotel complex at the top of a mountain, as the name implies. I left camp while it was still dark, and made it up there just in time for the sun to crest over the top of the distant mountains. The fact that I had to take the photo from a parking lot, rather than from the edge of the forest made it a little bit surreal. There was no way to access the forest from here because all access was “private property” of the resort itself. So after making my photos from the edge of the parking lot, I went back down the mountain to the other side of the Chittenden Reservoir and to the spot I had so appreciated just on the edge of the pristine wilderness of Lefferts Pond. I wasn’t even looking for beaver sign this morning, instead I was just trying to take in as much of the sensory experience of the place as I could, knowing it was my “last day” at Chittenden Brook. Tomorrow morning very early I will be leaving camp and making my way to a new location. I made one last drive up and down Wildcat road before starting my workday. The sunlight began to reach the pond and in the distance “smoke” was rising from the water. It looked like it was going to bea another beautiful day.

There was so much I still wanted to do in the part of the Green Mountain National Forest, but I had to make some choices, and I decided to give today to the more “touristic” aspects of the “Vermont experience” and go check out a waterfall and find some of the famous “covered bridges” in the area.

My first stop was for a short hike to see the Thundering Falls near Killington. Said to be the sixth tallest waterfall in Vermont, it’s a short easy hike across an open area of the Ottauquechee River flood plain which leads into a beautiful dense bit of northern hardwood forest. Once in the woods the path intersects the Appalachian Trail before reaching the dramatic waterfall. The falls cascade over deeply eroded rock for about 125 feet in two sections: the principal falls is the 80-foot lower falls, which horsetails above and past an observation deck elevated two stories above the brook; however the 22-foot upper falls, is arguably the more photogenic of the two.

Vermont has more than just a fair share of cascades and chasms — in the Green Mountains alone water tumbles off the slopes in streams and rivulets, brooks and rivers — the result of the last glacial melt. Waterfalls formed eons ago as water, looking for new ways to drain, cut down through steep sections of bedrock. And from the start, people were drawn to the roar of the ever-changing flow. Archeologists believe waterfalls were important places for Native Americans for both sacred and practical reasons. The falls were productive fishing areas and served as community gathering spots when the fish were running. They were also valuable as meeting places because they were distinctive geographical features that were widely known. Later, European settlers would use many of these falls to power mills and industry. And today waterfalls are a major attraction for tourists, photographers and nature enthusiasts of all stripes.

But the Thundering Falls were not “thundering” at all. In fact there was just the smallest trickle of water caressing a dramatically eroded white rock path that in turn sliced through the dark richness of the forest floor. The water was “missing.” A persistent drought has plagued Vermont throughout the summer and into September, leaving waterfalls mostly dry state-wide. According to state climatologist Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux, Vermont is actually experiencing five types of droughts at once: A “flash drought” — a rapid onset drought that deteriorates quickly — began between June and July. A “meteorological drought,” driven by scarce precipitation, has dried out soil and led to “agricultural drought.” As conditions worsened, lakes, rivers and streams were hit by a “hydrological drought,” while the impacts on food production and prices pushed the state into a “socioeconomic drought.” It has been Vermont’s worst drought on record, with low water levels around the state affecting aquatic ecosystems and prompting towns to conserve water. More worrying is the potential longer-term effect of the drought on the state’s agricultural resources.

Leaving the “falls” behind I exited the forest and noticed how the mountains across the way were already well on their way to showing their fall colors much earlier than usual — another result of the drought perhaps.

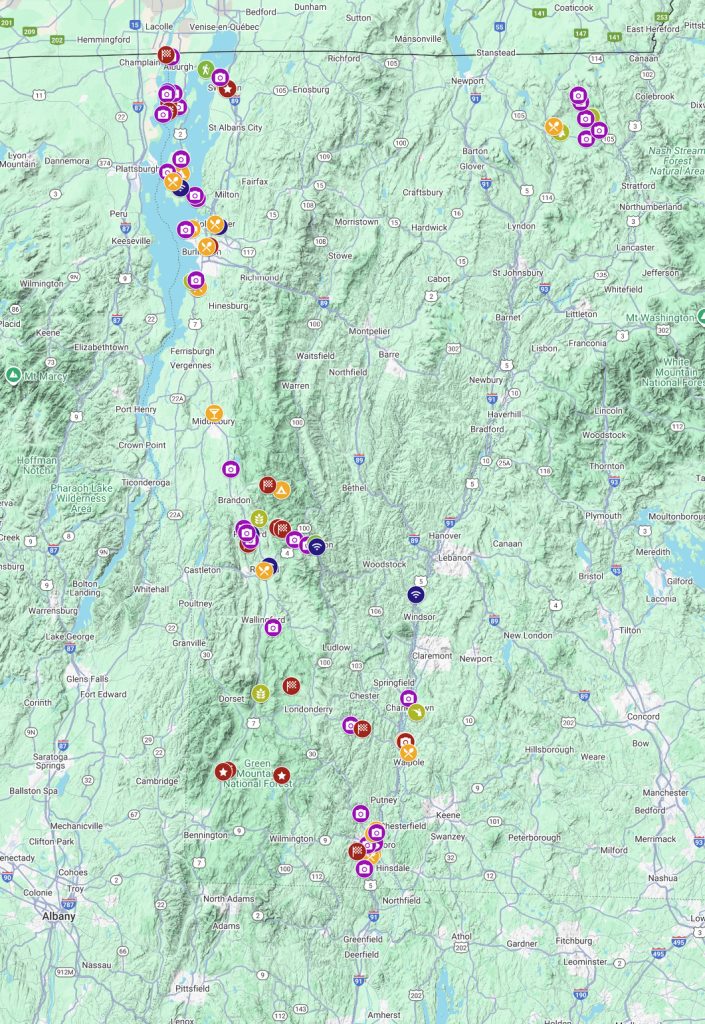

It was time to go chasing “checkpoints” — in this case some of the iconic covered bridges — that I had mapped out earlier in the day. Vermont boasts more than 100 covered bridges and ranks No. 1 in the nation for covered bridges per square mile. Many are more than a century old and most predate motor vehicles — some are said to be haunted. Covered bridges have become landmark centerpieces of the rural New England landscape, but they were originally simply a way of protecting critical infrastructure from the ravages of winter weather. The roof served to protect the bridge’s wooden trusses from rot — without a roof, the untreated wooden structures would deteriorate in just a few years. Uncovered wooden bridges typically have a lifespan of only 20 years because of the effects of rain and sun, but a covered bridge can last over 100 years.

My exploration of the bridges was centered around a stretch of Otter Creek near Pittsford, and I found the first one, the Gorham Covered Bridge, by following a rural road through some farmland. The bridge is oriented east–west across the north-flowing creek. Built in 1841, the single span “Town lattice truss” bridge is one of Vermont’s oldest surviving covered bridges. The bridge’s exterior is sheathed in vertical board siding, which ends short of the roof line, and is topped by a gabled roof covered in corrugated metal. I was surprised that the bridge itself was still in use and not simply an “attraction.” I had hoped to maybe set up some photos with the Jeep and the bridge, but it was too busy for that. I took my photos from one side, then drove through to the other side and got out and made a few more pictures of it before continuing on.

The next stop was the Cooley Covered Bridge, a smaller structure that crosses over Furnace Brook, a tributary of the main Otter Creek. Painted bright red, Cooley bridge was built in 1849 in the same single-span “Town lattice truss” style as the Gorham bridge. This type of construction allows for erecting a substantial bridge using simple planks and unskilled labor. The design, which uses many small, closely spaced diagonal elements to form a lattice, was patented in 1820 by architect Ithiel Town. It was a popular choice for constructing the many small bridges in rural areas of Vermont because it was less expensive than other styles. Like the Gorham Bridge, the Cooley Bridge is still in use, and there was a fair amount of traffic. Still, I managed to take a walk through it, though I had to be careful as the rural road is winding and local drivers go pretty fast and don’t really expect to see tourists walking through these bridges.

Continuing along the path of Otter Creek, the next stop is the Depot Covered Bridge. The Depot bridge was built about 1840, and underwent restoration in the 1980s when it was reinforced with steel stringers. It doesn’t have a name plaque or historical marker like some of the other covered bridges, but it is on the National Register of Historic Places. It remains a working bridge connecting the main village of Pittsford to the western part of the community.

From the Depot bridge, I looped around to the last of the bridges on my list, the Hammond Covered Bridge which spans Otter Creek in an east-west orientation. Built in 1842, it is 139 feet long, with an exterior finished in vertical board siding punctuated by square openings that provide light to the interior of the structure. In 1927, a flood swept the bridge 1.5 miles downstream but left the structure intact. Since it was still functional, the bridge was placed on barrels and transported back to its original location. The Hammond Bridge is closed to all traffic (vehicular traffic now crosses the creek via a steel and concrete bridge on Kendall Hill Road just south of the old bridge) and even blocked to foot traffic. It is a beautiful old bridge suffering from slight disrepair, but to me it was the most beautiful of all the bridges on my route today. Something about it’s worn wooden planks and slightly sagging build made it seem more “authentic” than the other well-maintained examples of the style. Or maybe it was the way the long span reflected in the creek below that gave it a special charm. In any case it was a great way to end my little loop around the covered bridges, and it was time to head back to camp for my final night at Chittenden Brook.

ABOUT THE JOURNEY

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads.org, set off on a fun overlanding adventure exploring around the state of Vermont for a few weeks in September. Driving and camping out of her 2019 JL Rubicon, she was able to check out several different regions and enjoy some local cultural and historic sites while en route to “Beaver Camp” at the Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center in Brattleboro. The 2nd Annual “Beaver Camp” is a workshop event dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts with workable solutions that allow the beavers to continue their important role as a keystone species restoring and conserving wetland ecosystems.

WHERE WE ARE

Vermont is part of the “New England” region of the United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. The geography of the state is marked by the Green Mountains, which run north–south up the middle of the state, separating Lake Champlain and other valley terrain on the west from the Connecticut River Valley that defines much of its eastern border. A majority of its terrain is forested with hardwoods and conifers. The Algonquian-speaking Abenaki and Iroquoian-speaking Mohawk were active in the area at the time of European encounter, but the history of the indigenous peoples here goes back about 12,000 years. The first humans to inhabit what is now Vermont arrived as the glaciers of the last ice age receded. Small groups of hunter-gatherers followed herds of caribou, elk, and mastodon through the grasslands of the Champlain Valley. At that time much of region was mixed tundra. The oldest human artifacts are 11,000 year old projectile points found along the eastern shore of the saltwater Champlain Sea. This time is known as the Paleo-Indian period. By about 8,000 years ago, the Champlain Sea had become the freshwater Lake Champlain and the climate was more temperate, bringing increased diversity of flora and fauna. By about 4,300 years ago, the forests were as they are today. Large mammals underwent extinction or migrated north, and the human population became reliant on smaller game and plants. Most of the state’s territory was occupied by the Abenaki, south-western parts were inhabited by the Mohicans and south-eastern borderlands by the Pocumtuc and the Pennacook. In 1609, Samuel de Champlain led the first European expedition to Lake Champlain. He named the lake after himself and made the first known map of the area. The French maintained a military presence around Lake Champlain, since it was an important waterway, but they did very little colonization. In 1666, they built Fort Sainte Anne on Isle La Motte to defend Canada from the Iroquois. It was abandoned by 1670. The English also made unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area in the 1600s. In 1724, they built Fort Dummer near what is now Brattleboro, but it remained a small and isolated outpost, often under attack by the Abenaki. Vermont became the 14th state of the United States on March 4, 1791. From north to south, Vermont is 159 miles long. Its greatest width, from east to west, is 89 miles at the Canada–U.S. border; the narrowest width is 37 miles near the Massachusetts border. There are fifteen U.S. federal border crossings between Vermont and Canada. Several mountains have timberlines with delicate year-round alpine ecosystems. The state has warm, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. The topography and climate make sections of Vermont subject to large-scale flooding, and extreme rain and flooding events are expected to intensify with climate change.