My plan this morning was to catch the sunrise at Chittenden Reservoir and I left camp in the dark of night to be there ahead of the sun. The only problem was I hadn’t realized that the sun would not “rise” over the mountains where I thought it would — or rather, that view was blocked by a little strip of land with lots of trees, and I couldn’t get an angle that would capture the “rise” from this side of the lake without running into the dam structure. Oh well, it was a beautiful and peaceful morning to sit on the edge of the shoreline looking out over the blue lake at the smoke rising from the water near the distant treeline. As I watched the smoke rise and dissipate, I heard the sounds of a lone kayaker slowly paddling towards the horizon. I thought the water must be cold and I was glad to be dry on shore.

The sun was up now, even though I didn’t get the dramatic “rise” moment, and if I hoped to find some beaver activity I’d better get over to the pond and wetlands area on the other side of the Reservoir. It was a quick drive and I was a bit familiar with the area now, so I went straight to the spot on Wildcat Road where the “channels” through the marsh parallel the road and parked the Jeep safely to one side. I began walking along these “channels” and the first thing I noticed was the remains of an old lodge or dam — weathered wood piled up and partially covered by sand and plant growth — it looked like nature was “reclaiming” it and the beavers hadn’t been there in a while. Though I remembered seeing a photographer right in this area yesterday morning, so maybe they were still around (or maybe he was photographing birds or other aspects of the wetlands themselves).

I continued exploring along the edge of the water until I was interrupted by the slow approach of a pickup truck coming down the trail. The driver leaned out the window in a friendly way and asked if I’d seen anything. I replied, no, I hadn’t seen anything, but I was looking for beavers. He nodded, and told me there was beaver activity in the general area and that further down the road, in the woods there were a number of dams. He explained that the dirt road that appeared to end on my GPS map actually continued all the way to an intersection, and near that intersection there was an active beaver lodge. He looked at my Jeep and said I would have no problem making it down there.

I was thankful for the “lead” and switched to my OnX Offroad map so I could see where the dirt road became an unmaintained Jeep trail (but still a legal road) and found the “intersection” he had referenced, then I set out to see what I could find. The first part of the drive went to the spot where I had turned around yesterday, thinking there was nothing beyond that point. I noted some cabins in the woods, and some of the tell-tale plastic tubing that meant someone was tapping the maple trees. Then I reached the point where the dirt road became rougher and narrower and there were no more cabins, just the forest all around me. I drove carefully because I was unsure of the condition of the trail ahead apart from the fact that it was too narrow to be able to turn around. The sun filtered in through the leaves by moment and I was glad to have found such a pretty trail. I noted a couple of dispersed camp spots, too.

As I neared the “intersection” I came out into a “clearing” of sorts, and the eerie beauty of a swamp-like landscape had me enchanted. I stopped to make some photos and there in the center of the swamp, surrounded by the start of fall colors in the forest, was a huge beautiful beaver lodge. The scene was perfect. The road continued as a tiny strip of land across the swamp, and some water was flowing, but it was nothing the Jeep had to worry about, so I crossed to the other side, parked and got out to look for beavers or at least some signs of their activity.

Soon enough the man who told me about this place came along with his dog. He pointed out another area that had activity but it was through the swamp itself, and I didn’t have on the right boots for bushwhacking. He noted the flowing water and wondered if the beavers were no longer there, saying that he was surprised the beavers would let the water “leak” and he thought maybe they had been “trapped” out. He seemed to feel like that was unneccessary and said he himself was a “live and let live” kind of guy and that these beavers weren’t bothering anyone, but he noted that not everyone thinks like that.

He and his dog finished their walk and left me to my photography. I made a few more shots, then started back to look for another spot he had mentioned. On my way out I stopped to say “thank you” and he smiled and waved as I continued down the trail. It was already too late to actually catch any early morning beaver activity so I headed towards town to make a new plan.

One of the cool things about Vermont is the fact that it is “small,” meaning that distances from place to place are not “vast” and so it seems like even though we are off-grid out in the wilderness with “no signal” we are never really very far from “civilization” either. A half-hour’s drive and we are in a town. That makes it possible to be out in the forest looking for beavers in the morning, and then at lunchtime check out a great “farm to table” restaurant in the city, which is exactly what I did. I rolled into the small city of Rutland around 1pm and settled in to a comfortable outdoor terrace table at Roots. I ordered the Labelle Farm duck breast pan-seared and served over risotto cake with a blueberry glaze & a dried cherry compote, and it was absolutely delicious. Then I took a short walk to look for some of the street art.

Rutland is a working-class city with a cute historic district and a history as one of the world’s leading exporters of marble. It has that red-brick old industrial look typical of once-vibrant cities that have experienced an economic downfall. But it also has a lively arts scene downtown which includes a series of cool wall murals. I didn’t have time to go looking for all of them, but I did find a few.

Then it was time to get back to scouting the backcountry. I decided to explore a different section of the Green Mountain National Forest, along FS10, also known as the Danby-Mount Tabor Road. Like many places in the National Forest this road was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s and the drive is very scenic as it goes up and over the mountains through a variety of ecosystems. This chain of the Appalachian Mountains was formed 400 million years ago by the former shoreline and continental shelf of an ancient ocean. The stresses of that shift led to vast deposits of schist, marble, and slate. Iconic for their steep inclines, the Green Mountains are the product of younger rocks ascending over older, continental shelf rocks below.

The first segment of the road heading from west to east enters the White Rocks National Recreation Area which encompasses 36,400 acres of majestic hardwood forest including Big Branch Wilderness, Peru Peak Wilderness, Big Branch Observation Area, and the White Rocks Day Use Area. I stopped to do some photographs by the bridge where the water flows down a series of boulders. The bright sunlight sparkled off the clear water and the effect of light and shadow created an ephemeral visual “texture” that was really cool. There are several trails that start from this day use area, including a short walk to a cascading waterfall on Bully Brook. Less than a mile up the Ice Beds Trail, a little climb leads to a viewpoint of the white rocks, a glacier-scoured cliff of Cheshire quartzite, which was used by Native Americans to make tools.

From the White Rocks, I continue the drive up the mountain to the next stop at the Big Branch Observation Area, which is a great spot to have a picnic lunch while looking out over the mountains for miles beyond. Further along the Forest Road I noted what looked like beaver habitat, and in fact spotted a few dams and one really nice looking lodge, but no beavers (which was normal for the time of day). What I couldn’t tell for sure was whether or not this was an “active” beaver site. I tried to look for the tell-tale signs of recent beaver “chew” but didn’t see any and I started to wonder if every time we see these beautiful open wetlands the beavers created, did it mean the beavers themselves were already gone, looking for new places with more trees to cut down. Or do the beavers stay in the place they create for a while. I think of all the places I have been to called “beaver pond” or “beaver meadow” where beavers themselves seem to be absent, but I have no answer to my questions. I will have to decide if I want to try to “stake out” one of these sites around sunset to see if any beavers show up.

My drive on Forest Service Road 10 took me out of the forest near the town of Peru, and it was time to turn around and start working my way back to camp. I decided to take a section of the Scenic Route 100 Byway north. This turned out to be a relatively busy highway that passes through a number of towns where gas (and probably everything) is more expensive. After the beautiful drive on the Forest Road, the Route 100 Byway did not seem very “scenic” to me apart from a small section of swampland near Gifford Woods State Park that looked like prime beaver habitat. There wasn’t any place to “park” but I managed to pull off the road and put my flashers on so I could go check it out. The light was coming down at an angle that made it difficult to really “see” into the depths of the swamp, but I could clearly see two beaver dams and a lodge. The dams were in good repair, and I had a feeling this was an active site, but I couldn’t stay there to wait for sunset and see if the beavers came out, as it was literally next to the highway with huge trucks passing at high speeds. I was sure that if the police passed by they would tell me I had to move, so I continued on and decided to make a sunset beaver stakeout at the wetlands below the Brandon Gap Mount Horrid overlook closer to camp.

I reached the Brandon Gap pull off just after the sun had gone down behind the mountain, and dusk fell on the beaver lodge below. I waited patiently until it had gotten too dark for photography, but there was no signs of the beavers.

Nevermind, I had a great day exploring and I felt like I accomplished a lot by the time I got back to camp and got the fire started. It was a beautiful warm evening and I stayed outside until quite late. I even saw a few stars peek through the thick canopy of trees as I sipped on a can of Woodchuck Pearseco cider before finally calling it a night.

ABOUT THE JOURNEY

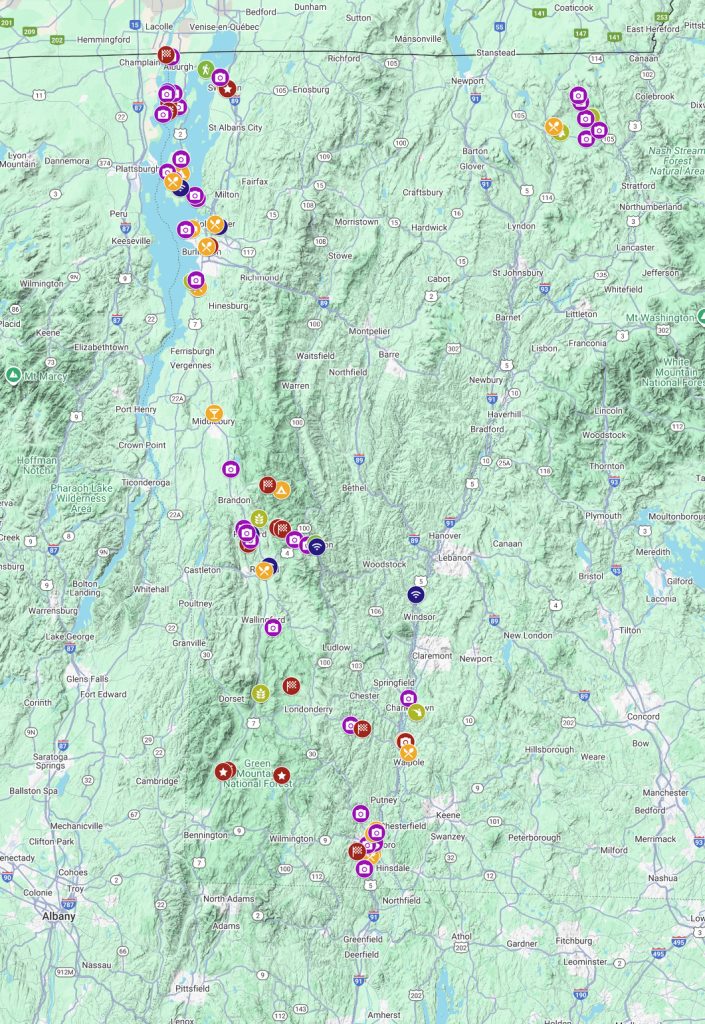

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads.org, set off on a fun overlanding adventure exploring around the state of Vermont for a few weeks in September. Driving and camping out of her 2019 JL Rubicon, she was able to check out several different regions and enjoy some local cultural and historic sites while en route to “Beaver Camp” at the Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center in Brattleboro. The 2nd Annual “Beaver Camp” is a workshop event dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts with workable solutions that allow the beavers to continue their important role as a keystone species restoring and conserving wetland ecosystems.

WHERE WE ARE

Vermont is part of the “New England” region of the United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. The geography of the state is marked by the Green Mountains, which run north–south up the middle of the state, separating Lake Champlain and other valley terrain on the west from the Connecticut River Valley that defines much of its eastern border. A majority of its terrain is forested with hardwoods and conifers. The Algonquian-speaking Abenaki and Iroquoian-speaking Mohawk were active in the area at the time of European encounter, but the history of the indigenous peoples here goes back about 12,000 years. The first humans to inhabit what is now Vermont arrived as the glaciers of the last ice age receded. Small groups of hunter-gatherers followed herds of caribou, elk, and mastodon through the grasslands of the Champlain Valley. At that time much of region was mixed tundra. The oldest human artifacts are 11,000 year old projectile points found along the eastern shore of the saltwater Champlain Sea. This time is known as the Paleo-Indian period. By about 8,000 years ago, the Champlain Sea had become the freshwater Lake Champlain and the climate was more temperate, bringing increased diversity of flora and fauna. By about 4,300 years ago, the forests were as they are today. Large mammals underwent extinction or migrated north, and the human population became reliant on smaller game and plants. Most of the state’s territory was occupied by the Abenaki, south-western parts were inhabited by the Mohicans and south-eastern borderlands by the Pocumtuc and the Pennacook. In 1609, Samuel de Champlain led the first European expedition to Lake Champlain. He named the lake after himself and made the first known map of the area. The French maintained a military presence around Lake Champlain, since it was an important waterway, but they did very little colonization. In 1666, they built Fort Sainte Anne on Isle La Motte to defend Canada from the Iroquois. It was abandoned by 1670. The English also made unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area in the 1600s. In 1724, they built Fort Dummer near what is now Brattleboro, but it remained a small and isolated outpost, often under attack by the Abenaki. Vermont became the 14th state of the United States on March 4, 1791. From north to south, Vermont is 159 miles long. Its greatest width, from east to west, is 89 miles at the Canada–U.S. border; the narrowest width is 37 miles near the Massachusetts border. There are fifteen U.S. federal border crossings between Vermont and Canada. Several mountains have timberlines with delicate year-round alpine ecosystems. The state has warm, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. The topography and climate make sections of Vermont subject to large-scale flooding, and extreme rain and flooding events are expected to intensify with climate change.