Got an early start on the day again because I just happened to wake up a little before 6am, and I decided to use the time to go scouting for beavers. Beavers are essentially nocturnal animals, but I figured it might be possible to catch some activity in the early morning around sunrise. I had heard there was some beaver activity around Lefferts Pond next to the Chittenden Reservoir and I jumped in the Jeep and headed in that direction. The sun rose while I was en route and there was a beautiful quality of light as it shone under a layer of clouds surrounding the mountains to the east. The area I was driving through was a rural farming region with tall corn covering the fields. Once off the main highway, the route to Lefferts Pond was a combination of dirt and gravel roads and it turned out to be a really pleasant drive even though I “missed” the actual sunrise moment.

The Reservoir and the Pond are connected and at a certain point the road splits with one side going to the Reservoir and the other to the Pond. I took the Pond side first in hopes of finding some beaver activity, or at least some signs of beavers, even though it was probably already too late to catch them out of their lodge. I drove along the side of the pond, past the parking area, following Wildcat Road until it separated from the pond’s edge. The whole area was heavily forested and I turned back taking a slow crawl through the section where the marshy edges of the pond meet the road with lots of little water channels that looked like the kind of place beavers might be. I didn’t see any but I did find a nice little “drive-in” spot that took me through the trees and right to the edge of the main pond, which looked more like a lake than a pond to me. It was a vast open water with what looked to be a few islands and some places that were thick with marsh grass. I could see some ducks in the distance and a band of fog clinging to the tops of far off mountains. It was a beautiful scene and I just stayed there awhile observing and appreciating the moment.

After leaving the pond’s edge, I retraced my path to where the roads split and this time I took the other side, which went right up to the top of the man-made dam, and then around the side to the Reservoir. Chittenden Reservoir is a quiet and pristine high-elevation lake formed when the Central Vermont Public Service dammed the East Creek in 1909. The land was bowl-shaped and fed by numerous streams, making it an ideal site for impoundment, that could serve the dual purposes of generating electricity and protecting against floods. Because the Reservoir lies within the National Forest, there is little lakefront development and much of the seven-mile shoreline remains unspoiled and rugged with many coves and small bays ideal for paddling.

The lake was calm and there were a few small boats out enjoying the morning. I walked along the rocky beach and could see some of the trees around the lake beginning to take on their fall colors. Following the shoreline around towards the dam, I found some nice sized boulders that made a perfect “sit spot” where I could just peacefully watch the ripples of water endlessly expanding until they disappear. I wondered to myself whether or not man-made lakes could have “tides” that changed the shoreline like the ocean, because it seemed like there were places where the water rose and fell. I could have stayed by the lake all day, but I had to get back on the road because I had a late-morning appointment later at an area farm.

The 560-acre Baird Farm has been a family operation for four generations. It was started in 1918 by Sara Baird, the great grandmother of Jenna Baird who runs the operation today with her husband Jacob. When Sara first began the farm the main focus was a dairy herd, with maple syrup production as a side line. The family milked their cows to make butter that was sold door-to-door in the nearby town of Rutland. In time the dairy herd grew and they began selling their milk to the Boston market and later to the local Cabot cheese plant. Then, as the economy shifted, the Bairds began switching their focus from the cows to the maple production, and by 1996 all the milk cows had been sold, and maple syrup became the farm’s main product. Today they produce a variety of maple syrup products that range from “regular” syrups of different strengths to syrups infused with other natural ingredients creating a whole range of interesting flavors.

I arrived at the farm in time for lunch and sat at the picnic table next to Jenna’s flower garden taking in the ambiance as I ate. At the center of the farm are the iconic red barn, farmhouse and silo. The “sugarhouse” is to the side along with a small retail shop in the front. There are some beautiful flower gardens, a wildflower field and a pumpkin patch where Jenna grows giant pumpkins. Each year around Halloween she has a “guess the weight” contest for her largest pumpkin which gets harvested and taken to an annual “giant pumpkin weigh-off.” Competition pumpkins often tip the scales at over 1,000 pounds. While I was there a few local residents came by to visit with Jenna and make a guess at the weight of the pumpkin. One of the women tendering a guess today had won the contest in a previous year, correctly guessing the exact weight! It was interesting to see how neighbors in this rural community support one another. Jenna and Jacob are engaged with the community around their farm and even let a neighbor graze his cows on their land. Cooperation among neighbors seems to be more common here — some of the maple trees Bairds taps are on land that isn’t owned by the farm directly, and they make arrangements with the landowners to compensate them with money and syrup in exchange for the right to gather their sap.

As I was finishing my lunch, Jenna suggested I take a stab at guessing the pumpkin’s weight, and while I had absolutely no clue as to how much a giant pumpkin could weigh, I made a guess anyway. I tried to reason it out by comparing the pumpkin’s size to a person, which I would later learn was a mistake, because apparently pumpkins are much denser than humans, lol! Nevermind, it was fun to be part of the game. When I told them how low I had guessed, the woman who had won the contest before, said she guessed a little low this year, too. We won’t find out the exact weight until after it is harvested and brought to the weigh-off. But giant pumpkins were not the reason for my visit–I was here to learn about the Baird’s maple syrup production. I joined Jacob for a walk around the property as he explained a little about how they make syrup from tree sap today.

We began with a visit to the “sugar bush,” which is how they refer to the stands of maple trees that grow all over this part of Vermont. The Baird’s trees are all wild maple trees that grow in stands on the mountains surrounding their property, and Jacob and Jenna tap roughly 15,000 trees each year to collect their sap. The syrup is made by boiling down and concentrating the pure sap with no additives or other ingredients and it takes 45-50 gallons of sap to make just one gallon of syrup. While the process is essentially the same today as it was in Jenna’s great grandmother’s time, it has been modernized and streamlined in ways that make it possible for the farm to produce more syrup in a sustainable way.

And that’s important because the demand for quality maple syrup is growing. Vermont produces about 50% of the Maple syrup in the United States and, according to Jacob, that demand has quintupled over the past 15-20 years as people want more natural and less processed sugars. People are also finding new and innovative ways to use maple syrup — they are cooking with it and using it in marinades and baking as well as mixing it into different kinds of beverages. Small family farms like the Bairds remain competitive by focusing on quality, which starts with an organic “certification.” All the Baird Farm products are certified organic and all the work is done personally by the family members–including tapping all those trees.

They typically start the process in January, drilling a small hole in each tree and inserting a “tap” which gets connected to a series of plastic tubing that collects the sap. The process is aided by vacuum suction which draws the sap through the “lines” to larger tubes and on into vats. The Bairds have over 100 miles of tubing carrying sap to the sugar house. It’s like a sap superhighway system. It takes three people several weeks to tap all the 15,000 trees, and they don’t usually finish up until sometime in March when freezing nights and warm days cause the maple sap to flow from the trees. Once the sap is collected in the sugar house it gets boiled down into syrup, then bottled in different batches according to color — gold being the sweetest, amber being the most popular, and dark being the most robust in flavor.

When the sugaring season is over in April, the taps are removed and the holes in the maple trees begin to heal. After a couple of years, the holes are completely filled with new growth of wood. Most maple trees live to be over 150 years old and some of the very same trees Jenna and Jacob tap today were first tapped by Sara Baird over one hundred years ago.

As I left the Baird Farm I was positively impressed by Jenna and Jacob’s commitment to being good stewards of the land and keeping the forest healthy. I drove back along another dirt road, now noticing the many maple trees everywhere around me. My mind wandered and I wondered who first discovered that you could get sugar from a tree. It turns out that maple sugar has been a part of American history since long before Europeans settled here. Written history dating back as far as 1609 records the Native American process for creating sugar from maple sap and the Iroquois have a legend that tells how it was discovered. According to the legend, an Iroquois Chief named Woksis threw his tomahawk at a maple tree in the cold of winter. The next day, the sun warmed the sap inside the tree, and from the hole sprung forth the tasty syrup. Woksis’s wife cooked their meat in the sap, and it was so delicious that the people began to make maple sugar a part of their diet.

Before returning to camp, I had one more stop to make. I wanted to visit the Woodchuck Cider House to pick up some local “hard cider” to enjoy back at camp. Woodchuck has been crafting hard cider since 1991, fermenting innovative ciders with flavors like Pearseco and Blueberry. I wasn’t sure what to choose so I ordered a “tasting” flight. After enjoying the samples, I still couldn’t decide on only one flavor, so I bought a “variety pack” and put it on ice in the cooler, then returned to my Chittenden Brook campsite.

I got the fire going quickly then opened up a can of the “Granny Smith” cider to sip while preparing my dinner. As darkness fell over the forest I moved a little closer to the fire. It was a nice way to end a very good day.

ABOUT THE JOURNEY

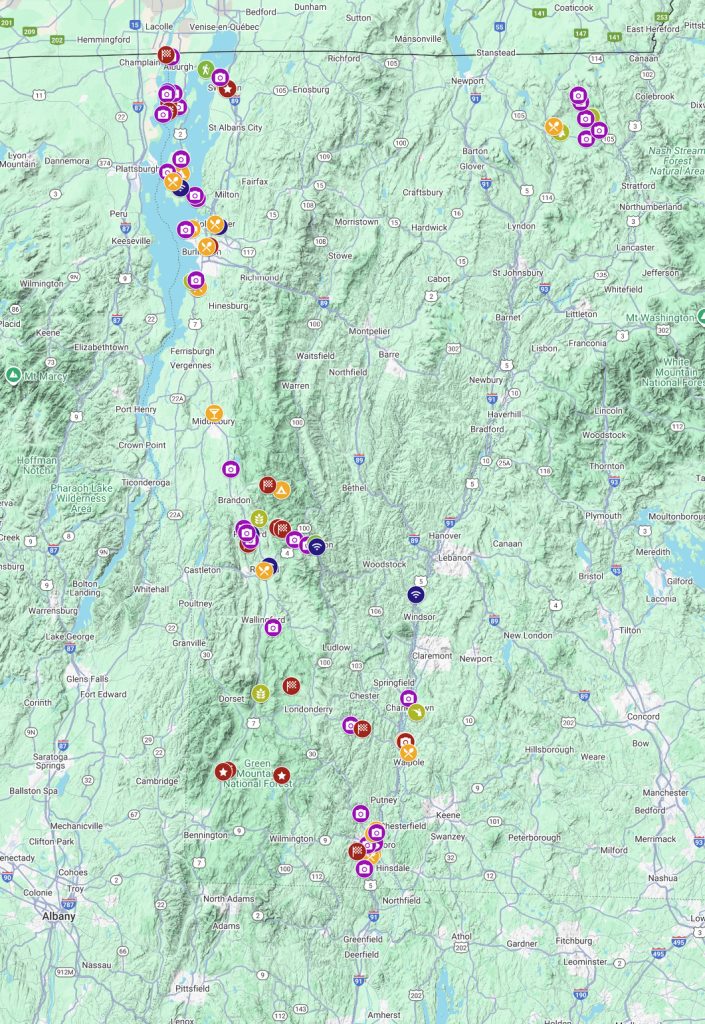

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads.org, set off on a fun overlanding adventure exploring around the state of Vermont for a few weeks in September. Driving and camping out of her 2019 JL Rubicon, she was able to check out several different regions and enjoy some local cultural and historic sites while en route to “Beaver Camp” at the Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center in Brattleboro. The 2nd Annual “Beaver Camp” is a workshop event dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts with workable solutions that allow the beavers to continue their important role as a keystone species restoring and conserving wetland ecosystems.

WHERE WE ARE

Vermont is part of the “New England” region of the United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. The geography of the state is marked by the Green Mountains, which run north–south up the middle of the state, separating Lake Champlain and other valley terrain on the west from the Connecticut River Valley that defines much of its eastern border. A majority of its terrain is forested with hardwoods and conifers. The Algonquian-speaking Abenaki and Iroquoian-speaking Mohawk were active in the area at the time of European encounter, but the history of the indigenous peoples here goes back about 12,000 years. The first humans to inhabit what is now Vermont arrived as the glaciers of the last ice age receded. Small groups of hunter-gatherers followed herds of caribou, elk, and mastodon through the grasslands of the Champlain Valley. At that time much of region was mixed tundra. The oldest human artifacts are 11,000 year old projectile points found along the eastern shore of the saltwater Champlain Sea. This time is known as the Paleo-Indian period. By about 8,000 years ago, the Champlain Sea had become the freshwater Lake Champlain and the climate was more temperate, bringing increased diversity of flora and fauna. By about 4,300 years ago, the forests were as they are today. Large mammals underwent extinction or migrated north, and the human population became reliant on smaller game and plants. Most of the state’s territory was occupied by the Abenaki, south-western parts were inhabited by the Mohicans and south-eastern borderlands by the Pocumtuc and the Pennacook. In 1609, Samuel de Champlain led the first European expedition to Lake Champlain. He named the lake after himself and made the first known map of the area. The French maintained a military presence around Lake Champlain, since it was an important waterway, but they did very little colonization. In 1666, they built Fort Sainte Anne on Isle La Motte to defend Canada from the Iroquois. It was abandoned by 1670. The English also made unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area in the 1600s. In 1724, they built Fort Dummer near what is now Brattleboro, but it remained a small and isolated outpost, often under attack by the Abenaki. Vermont became the 14th state of the United States on March 4, 1791. From north to south, Vermont is 159 miles long. Its greatest width, from east to west, is 89 miles at the Canada–U.S. border; the narrowest width is 37 miles near the Massachusetts border. There are fifteen U.S. federal border crossings between Vermont and Canada. Several mountains have timberlines with delicate year-round alpine ecosystems. The state has warm, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. The topography and climate make sections of Vermont subject to large-scale flooding, and extreme rain and flooding events are expected to intensify with climate change.