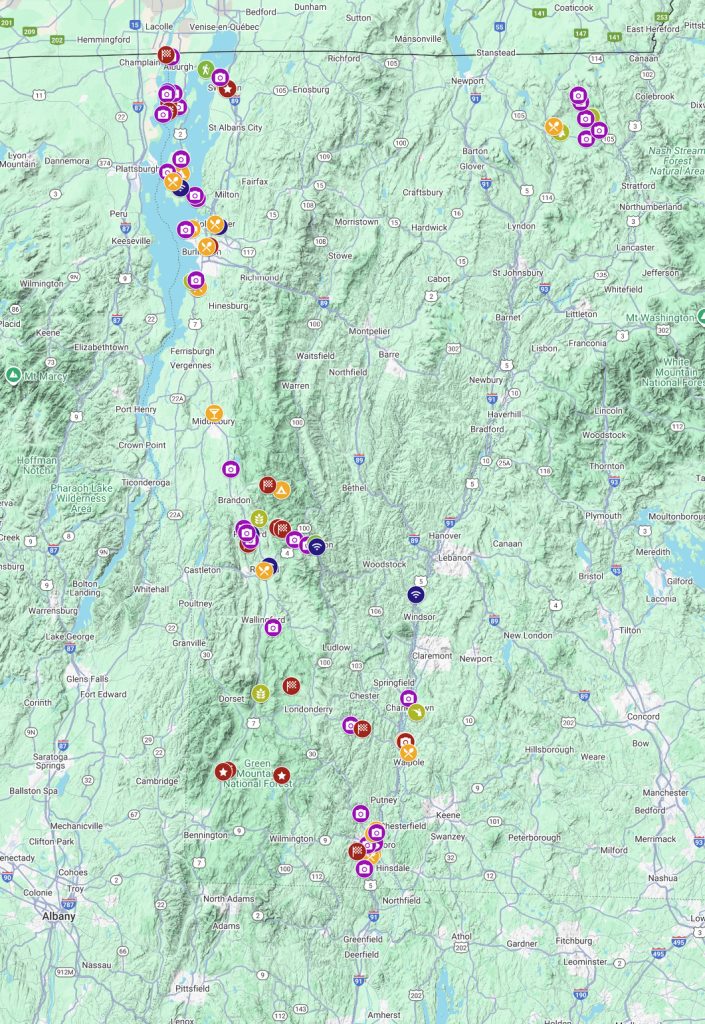

Every journey has that one day that is just so very long it seems like a whole weeks worth of adventure was crammed into less than twenty four hours, and today was that day. The longest day. But a great day nonetheless. It was a mix of surprises, disappointments, discoveries and epic landscapes all rolled into one big marathon that would take me to the western “border” with New York and the actual “frontier” with Canada, then across the state to the eastern “border” with New Hampshire and finally back to the Champlain Islands. I left in the dark and I would return in the dark, but I was very very glad I took all the optional detours.

Wake up was before first light, as I was determined to get a nice sunrise photo from Grand Isle where I could finally get a view on the horizon at sun up. Of course, I still faced the issue of so much private property blocking access to views, but luckily Vermont Fish and Wildlife is proactive about maintaining public access to the waterways, and so there were opportunities to find just the right spot at one of the public boat ramps. I had spotted the location yesterday on my way to camp and thought it would be perfect so I rolled up to the water’s edge as the first hints of morning light appeared over the mountains transforming the black night into vivid shades of blue. The water was still and there was a quiet calm with no activity at all as I waited patiently to see exactly where the sun would “rise” over the scene.

A hint of reddish pink signaled the passing of time and I heard the first early birds stirring with the coming of the new day. In the distance I could see a whole flock of ducks still sleeping, their silhouettes motionless and black. Slowly the sky transformed itself into first a bright red, then a warm golden glow as the sun approached. A flock of geese flew across the sky in formation, making a loud raucous honking symphony as they went, as if they were the alarm clock telling the rest of the wildlife it was time to wake up. A wisp of smoky fog rolled over the water and so the day began.

I looked at my maps to determine the “best” route to follow northward, but there was essentially only one — US Route 2 — that would get me to my first “destination” of the day. And as I plugged the location into my GPS I was faced with the day’s first “challenge”. I had made a well-thought out plan to attend a program about the Algonkian and Iroquoian peoples during the American revolution being presented by Drew Shuptar-Rayvis, a cultural ambassador from the Pocomoke Nation, at the “Fort Montgomery State Historic Site.” Fort Montgomery is clearly indicated on the map just south of the Canadian border near Rouses Point. However, the GPS was telling me to go 300 miles SOUTH — a five hour drive — to reach the “Fort Montgomery State Historic Site”!!! Apparently the program and the “state historic site” are not actually at the site of the “Fort Montgomery” I was heading to. I would have to skip the historical presentation and just try to go to the actual fort site. It was a bit of a disappointment, but I still had a full day of adventuring ahead, and so I set out on my planned route north, to the “border” with New York state and the “frontier” with Canada to find the old fort.

The drive was lovely in the early morning calm, following the chain of islands to the final causeway bridge that spans the actual “border.” From the Vermont side I could see the fort off in the distance and I pulled over to make some photos. As I exited the Jeep I was a bit startled by the sound of gunshots nearby. Duck hunters were busy along the shoreline where they had set up an amazing “blind” on a small boat completely covered with marsh reeds. I didn’t disturb them, and went about my own business photographing the fort ruins bathed in the warmth of the morning light, then I crossed over the bridge to New York to see if I could actually get into the fort itself. I followed the road down under the bridge to what looked to be a boondocked RV on the water’s edge, but to my great surprise, it was actually the official “frontier” — the US Customs and Border Control point for anyone crossing by water. No one was there but me and the dirt road that seemed to lead to the fort ruins was blocked by a locked gate. So this was as far as I was going to get.

It was a beautiful morning and I had been up for hours and hadn’t eaten yet, so I decided to picnic right on the edge of the water in a nice shady spot from where I could see the ruins of the fort. I pulled out my camp chair and cooler and made an impromptu breakfast while just appreciated the calm of the morning. And I had to think about my optional plans for the rest of the day. Now that I didn’t have the interpretive historical program I had more time, and I had made a detailed optional plan to try to go look for moose in a part of Vemont known as the Northeast Kingdom. It was quite far but I had scoped out several potential routes where it might be possible to see them. It would be a longshot, but it would also be an opportunity to see another part of the state and check out the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge there. I could scout around till sunset when maybe the moose would be out, and leave when there was no longer enough light for photography. As I mulled over the idea and reviewed the maps I convinced myself that it was a good idea and a nice “consolation prize” after missing the historical presentation.

The duck hunters were gone by the time I crossed back into Vermont to begin the journey east to look for moose. Of course, moose would not be out in the middle of the day, so I planned several stops to do some exploring on my way to the Conte NWR. Not far from the causeway bridges back on the mainland I was following the path of the Missisquoi River into another large National Wildlife Refugee that protected a big swath of wetlands.

The Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1943 to provide habitat for migratory birds. In fact, Missisquoi hosts the largest concentration of waterfowl on Lake Champlain with wood ducks, mallards, green-winged teal and ring-neck ducks the most abundant species. Much of the refuge is only accessible by water and there are two public boat ramps from which to explore the Missisquoi River and Lake Champlain. There is no “scenic drive” route but there are five walking trails located off of State Route 78 and Tabor Road.

The refuge and the river are named for the Missisquoi, an Abenaki people who’s homeland covered the area beginning at the northeast shore of the Missisquoi Bay and extending east along the Missisquoi river. The Missisquoi took part in a vast trade network that reached from the Atlantic Ocean to an Anishinaabe territory in the Great Lakes, with Lake Champlain in between — an important center for exchange connecting the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Abenaki people. The Missisquoi’s ancient village was situated along the lower Missisquoi River and the vast Missisquoi delta. Archaeological studies have pinpointed the ancient village’s location, uncovering a large longhouse there in 2015. Some Missisquoi Abenaki people still live in this area and in 2012 the State of Vermont officially recognized the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi as a tribe. Their tribal headquarters are in the village of Swanton.

The tribal offices were closed as it was a Saturday, but I stopped by anyway, to try to see some of the totem poles that are scattered around Swanton. Abenaki “totem poles” are actually wooden carvings that share cultural and historical stories, distinguishing them from the totem poles of the Pacific Northwest. These modern works of art, reflecting Abenaki tradition, were carved by Richard Menard who served as Chief of the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi from 2019-2022. Sometimes working with his grandson, Menard uses white cedar taken from the banks of the Missisquoi River less than 1,500 feet from the Abenaki ancient burial grounds to create the towering poles. One of the totem poles stands at the site of the First Church of Vermont on Monument Road overlooking the river.

A neatly mowed lawn marks the spot which is designated a “state archaeological landmark”, but nothing of the church remains. Instead in the middle of the lawn there is a stone monument with a cross and inscription commemorating it as the location of the first church built in Vermont. It was established by the Jesuits around 1700 to serve as a Catholic mission to the Abenaki people, whom the missionaries referred to as the St. Francis Indians. Not far from the monument, the totem pole rises with the carved animals ascending high into the blue sky. Each animal has a meaning. Near the base is the Turtle which symbolizes Mother Earth, and has thirteen squares on its back representing the thirteen original old Abenaki villages. The Bear symbolizes medicine, power, protection It stands at the Western Gate and provides the Abenaki people with medicines. The Otter reminds people to be playful and not be tricked into situations that would destroy their unity. Amik, the beaver, represents wisdom, industriousness, and environmental harmony. It is seen as a skilled builder who works patiently and persistently to create a sustainable environment for its family and community. The Salmon symbolizes perseverance, self-sacrifice, and abundance. The Eagle symbol sits atop all of creation. Eagles are sacred spiritual beings that give the people a direct connection to the creator. The Eagle guards the Abenaki’s Eastern Gate and carries the people’s prayers to the heavens.

After leaving the Totem Pole site, I realized I was pretty hungry so I decided to stop for lunch at the Green Mountain Bistro in downtown Swanton. I installed myself on the outdoor terrace overlooking the main square, and while I was eating a pickup truck passed by pulling what looked like the “duck blind” boat I had seen early this morning. I would have liked to follow it and talk to the hunters, but I was in the middle of lunch and they drove off in the opposite direction from where I was heading.

I picked up the route eastbound continuing on towards the Conte NWR, which was still 100 miles away. I wouldn’t stop again until I reached Brighton State Park in the region known as the “Northeast Kingdom,” but the drive got unintentionally more interesting when I took a dirt road up over a mountain pass known as Hazen’s Notch. Hazen’s Notch was named after Moses Hazen, who in 1779 led the construction of the Bayley Hazen Military Road, which was supposed to go into Quebec and facilitate an invasion of Canada during the American Revolutionary War. However this is as far as it got before construction stopped. The notch is defined by the cliffs of Sugarloaf Mountain to the north and by Haystack Mountain to the south. The area is known for the rugged beauty of its steep cliffs and the road passes through heavily forested terrain. It made for a beautiful drive.

When I got to Northeast Kingdom, the landscape itself was exciting. It felt like real wilderness, everywhere around me were thick woodlands interspersed with wetlands, clear cuts and other boggy habitats. If I was going to see a moose this would definitely be the right kind of place. But it was still too early in the afternoon to go looking for them, so I decided to check out some of the dirt roads that run through the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge. The Conte NWR is huge, with nearly 40,000 acres running across New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The section that I was exploring, part of the Nulhegan Basin Division, is located in the most remote part of Vermont just a few miles south of the Canadian border.

I stopped first at the Visitor Contact Station, which was unmanned but open, and I picked up the current trail map. That turned out to be important, because a number of roads that were on GPS maps were actually gated and locked, and to get deeper into the refuge I had to use a very specific route.

I turned onto dirt near the Stone Dam site at the intersection of VT Route 105 and the Nulhegan River, where thick stands of spruce and fir trees stretch as far as the eye can see. The dam site was an important part of the lumber industry that was booming in this area of Vermont throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Without roads or vehicles to move the logs, workers piled up millions of logs along tributaries, or streams that flow into larger bodies of water. When the snow melted in spring, workers opened the dams, and the logs would float downriver as their way of transportation. To make the log drives work, they reshaped the Nulhegan River and its tributaries to prevent log jams. The sluice dam here used to control the flow of logs from the Nulhegan River into the Connecticut River.

But reshaping the rivers came at a steep price. Without trees lining the river, water temperatures increased and the banks eroded. Flows washed sediment out to larger bodies of water. Dams blocked fish from moving to important areas for their life cycles. Future logging roads used culverts that prevented fish and other aquatic wildlife from moving through. Since these log drives, brook trout populations declined due to the impacts to their habitat.

Today the Conte NWR works with local organizations to restore the biodiversity of the river and its tributaries. More than ten miles of streams have been restored on the refuge https://www.fws.gov/story/2020-11/chop-drop-and-roll, and over 20 miles have been restored across the watershed. Over a three-year period since restoration projects started there has been a whopping 150 percent increase in brook trout abundance and size in area, according to the US FWS.

From the site of the Stone Dam I drove on deeper into the woods, stopping for a few short hikes. The Nulhegan Basin Division has four elevated boardwalks that lead to observation points in different parts of the refuge. At the Yellow Branch site, the elevated viewing platform overlooks a beaver wetland, but I didn’t see any beavers. Still, the afternoon light spilling through the early autumn colors made everything seem magical on the trails. And the fact that I seemed to have the whole forest to myself made it even more special. I drove all the way to Lewis Pond and then up a mountain trail that led to a short hike out of the woods and into a clearing with a panoramic vista of the Nulhegan Basin and the surrounding landscape. It was almost sunset, and normally a good time to begin “wildlife watching,” and I drove back to Lewis Pond in hopes of seeing a majestic moose.

I was a bit disappointed when I didn’t see even a squirrel, let alone a beaver or a moose. It was getting dark now, and without enough light to make a photo, it was time to start back towards pavement. By the time I reached State Route 105 it was definitely night. I decided to take a different route westbound to avoid driving the rough rutted dirt road up over Hazen’s Notch in the dark. I settled in for the long drive back to Grande Isle, and just after leaving the town of Island Pond, I saw some kind of motion or reflection up ahead and slowed down as I wasn’t sure if it was just a play of headlights reflecting off a puddle or if there was actually something there. As I rolled slowly forward I saw the hulking form of a big black bear crossing right in front of the Jeep. A black bear, on a black tar road, in the black of night — it’s amazing I saw it with enough time to safely stop. The bear ran off into the woods on the other side of the road and I breathed. I had been looking for wildlife all day, but I really didn’t want to come across any more animals in the dark.

Cautiously I continued on my way, and luckily I had no more animal encounters. I pulled into camp back at Grand Isle around 1 a.m. exhausted but very happy with my day. Tomorrow I will “sleep in” and wake up whenever I wake up.

ABOUT THE JOURNEY

JoMarie Fecci, of USnomads.org, set off on a fun overlanding adventure exploring around the state of Vermont for a few weeks in September. Driving and camping out of her 2019 JL Rubicon, she was able to check out several different regions and enjoy some local cultural and historic sites while en route to “Beaver Camp” at the Bonnyvale Environmental Education Center in Brattleboro. The 2nd Annual “Beaver Camp” is a workshop event dedicated to resolving human-wildlife conflicts with workable solutions that allow the beavers to continue their important role as a keystone species restoring and conserving wetland ecosystems.

WHERE WE ARE

Vermont is part of the “New England” region of the United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. The geography of the state is marked by the Green Mountains, which run north–south up the middle of the state, separating Lake Champlain and other valley terrain on the west from the Connecticut River Valley that defines much of its eastern border. A majority of its terrain is forested with hardwoods and conifers. The Algonquian-speaking Abenaki and Iroquoian-speaking Mohawk were active in the area at the time of European encounter, but the history of the indigenous peoples here goes back about 12,000 years. The first humans to inhabit what is now Vermont arrived as the glaciers of the last ice age receded. Small groups of hunter-gatherers followed herds of caribou, elk, and mastodon through the grasslands of the Champlain Valley. At that time much of region was mixed tundra. The oldest human artifacts are 11,000 year old projectile points found along the eastern shore of the saltwater Champlain Sea. This time is known as the Paleo-Indian period. By about 8,000 years ago, the Champlain Sea had become the freshwater Lake Champlain and the climate was more temperate, bringing increased diversity of flora and fauna. By about 4,300 years ago, the forests were as they are today. Large mammals underwent extinction or migrated north, and the human population became reliant on smaller game and plants. Most of the state’s territory was occupied by the Abenaki, south-western parts were inhabited by the Mohicans and south-eastern borderlands by the Pocumtuc and the Pennacook. In 1609, Samuel de Champlain led the first European expedition to Lake Champlain. He named the lake after himself and made the first known map of the area. The French maintained a military presence around Lake Champlain, since it was an important waterway, but they did very little colonization. In 1666, they built Fort Sainte Anne on Isle La Motte to defend Canada from the Iroquois. It was abandoned by 1670. The English also made unsuccessful attempts to colonize the area in the 1600s. In 1724, they built Fort Dummer near what is now Brattleboro, but it remained a small and isolated outpost, often under attack by the Abenaki. Vermont became the 14th state of the United States on March 4, 1791. From north to south, Vermont is 159 miles long. Its greatest width, from east to west, is 89 miles at the Canada–U.S. border; the narrowest width is 37 miles near the Massachusetts border. There are fifteen U.S. federal border crossings between Vermont and Canada. Several mountains have timberlines with delicate year-round alpine ecosystems. The state has warm, humid summers and cold, snowy winters. The topography and climate make sections of Vermont subject to large-scale flooding, and extreme rain and flooding events are expected to intensify with climate change.