[rev_slider f-jeepschool]

Key to doing well in the Rallye Aicha des Gazelles is the ability to drive straight over as much as possible. The more we have to “go around,” the greater the risk of losing our heading. And with a capable Jeep, there is no reason we shouldn’t be able to go “over” most anything we will come across during the competition. The only limit will be our driving and navigational skills.

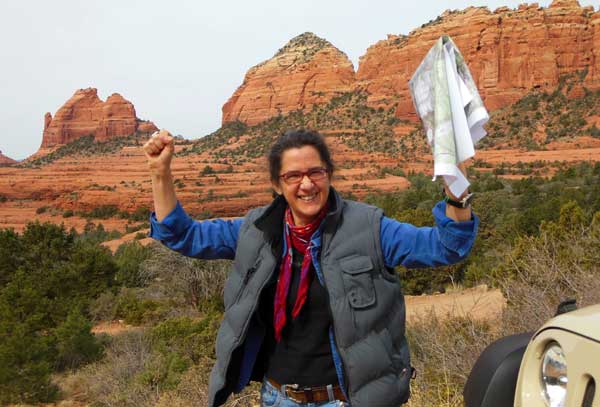

The magnificient red rock country around Sedona exudes the freedom of the American West and provides plenty of opportunity to hone desert driving skills. It’s as if Mother Nature created a giant playground for the Jeep where we can push the limits of the vehicle’s capabilities surrounded by surreal natural beauty.

This is the first time Niki and I are able to train together as a team in a real desert setting, and we’re spending an intensive week doing trails and navigational exercises, as well as getting instruction from Nena Barlow, owner of Barlow Jeep School and expert in all things Jeep and desert. One of a select group of 4×4 trainers certified by the International 4wd Trainer Association, Barlow has explored the backcountry of the Southwest by Jeep, horse, and hiking boots her whole life. Her extensive knowledge of the desert terrain makes her an unparalleled resource, as we try to learn the specificities of driving a Jeep across the Sahara.

Today we are focused on the Jeep and it’s capabilities. We are driving one of Barlow’s slightly modified Rubicons built to handle any of the area trails with ease. It is an amazingly able vehicle, and we are reviewing in detail the limit of the obstacles it can go over so we will know what we really DO have to go around.

As we drive over cracks, crevices and loose rock, we are developing an innate awareness of where the critical parts of our vehicle are in relation to these “obstacles.” We are concentrated on the trail in front of us, but Barlow is assessing our strengths and weaknesses as a unit, determining the best way to get us to perform as a synchronized team. It is all about communication, accuracy and precision — it is crucial that Niki and I see things from the same perspective as we navigate the landscape.

Crossing a dry wash, we stop to practice picking lines. Barlow shows us the difference between the “smart” line and the “interesting” line, and for training purposes encourages us to navigate the “interesting” line. Of course in the “real world” we would take the “smart” line. But in taking the “interesting” line now, we are learning the skills to handle more difficult terrain.

Both Niki and I exit the Jeep to evaluate the route. She will spot me over the complex section, guiding my tire placement so that it is precise, while making sure the “soft” spots of the Jeep’s underbelly are clear. We agree on a line, and then we drive it, getting familiar with the way we will need to operate in the desert.

Scenic Jeep trails encourage a slow and easy pace of driving, stopping, exploring on foot and taking lots of pictures. However, for the Rally we have to drive long distances in a reasonable amount of time. There’s a need for speed. Sometimes. We need to know when we can go fast, and how fast we can go on different types of terrain.

To get a feel for operating across changing landscapes, Barlow has put us out on a series of criss-crossing backcountry trails where flat dirt roads transition to more complex rutted trails with deep twisted v-ditches and steep inclines. Under her watchful eye, we can “push the envelope.”

Reaching the base of a steep incline, we are faced with a wide ditch on a narrow section of trail, and as Niki and I review the options, we find we have differing ideas about how to approach it. Niki’s line is straighter, but will put the Jeep in a more off-camber posture. My preferred line will keep the vehicle “flatter” but is harder to drive. As we discuss the pros and cons, Barlow interjects with a third possiblity that neither of us had considered.

We decide to repeat the obstacle, testing the outcomes of the three different lines. It is a process of discovery. And it’s fun. But most importantly we are building the foundation of a solid working method as a team.

Our next “trail” was a dried river bed full of rocks and boulders. There was no “path” or tracks from other vehicles — just a ribbon of rock. At first glance it seemed impossible to drive across, as we focused on the many HUGE rocks strewn among the slightly smaller ones — there were pointy ones and round ones, well-embedded ones and loose ones. It was a real puzzle, and the sound of metal scraping rock was not so pleasant when I misjudged the relative height of rock, tire and earth.

Potential damage to the vehicle in this kind of terrain meant we really needed to make a coordinated effort to analyze the obstacle and pick the best line. Explaining how to break the problem down into manageable segments, Barlow walked us over the rocks, pointing out the ones that might give us the most trouble, then she turned it back over to us to figure out. This time Niki and I agreed quickly on a line. It was the driving that would be slow.

Niki was totally concentrated on the tires and rocks. I was totally concentrated on following Niki’s precise direction and keeping solid control of the Jeep at all times. If I let the terrain “drive” the vehicle we could get into real trouble. We moved forward little by little at a “crawling” pace, as she worked to keep an eye on the underside of the Jeep while guiding me to place each tire exactly where it needed to go. It took us almost an hour to get over the rocks. Considering the distances we will need to travel during the Rally, we were moving way too slow.

Our lack of speed didn’t seem to phase Barlow, who answered our concerns with her signature smile while telling us to turn around and go back over the rocks in the other direction! We were learning what to look for and how to avoid getting stuck. This time we were quicker, getting back across in roughly a quarter of the time.

Moving from “micro” terrain assessment to “macro” land navigation, we set out with topo maps in hand to get a feel for translating the landscape from 2D to 3D. Our overview area map is printed to the same scale as the Gazelle Rally maps (1:100,000) to give us a realistic sense of what such a map will and will not show. From the top of House Mountain, with a 360-degree view of the surrounding area, we attempt to match up the contour lines on the map to the three-dimensional landscape in front of us. Right away we see discrepancies between the map and the real world. Things that are big and dramatic to our eyes, are not quite big enough to merit inclusion on the map, and other bits of rock formations that we identify as individual pieces, are actually part of larger land masses and so are not separately noted on the map. Instead they are included in the contours of the larger non-descript masses. This is confusing.

Orienting the map with the compass, Barlow shows us how to match up the rocky hills with the appropriate contours to estimate our exact position. She is trying to teach us to “look” and “see” in a more comprehensive way, but it is hard to focus on maps and navigation when there is just so much eye candy everywhere.

Looking out to the far off mountains on the eastern edge, in the direction of the paved road, we identify a few key points of reference in the landscape as well as closer intermediate waypoints that we could use as “guide posts.” Barlow explains that the real”challenge” would be in keeping track of our direction as those reference points disappear or change appearance when seen from a different angle.

We take some photographs of our “reference points” so we don’t forget what they look like, as our urban eyes are not used to distinguishing differences in the details of mountain peaks. Then we roughly measure the distance to the first way point, and pick up the trail which zig-zags its way downhill. We lost sight of the “big” mountain in the distance as soon as we descended into the first wadi.

Keeping an eye on the distance travelled, we knew where we should be roughly when we came back up, however we couldn’t be sure of the direction. To determine our “exact” position we had to use crude triangulation. Barlow guided us through the process and we continued onto the next segment of trail much more aware of our surroundings. Visually tracking our progress now while we drove, we were internalizing the lesson.

As we came out onto the last segment of the main trail headed back to the tar road, a coyote ran for cover in the brush and we could see the big mountain again.

Putting it all together on our last day in Sedona, we set out on a course that would give us an excellent simulation of the real challenges we will face during the Gazelle event. We had a big map and the GPS coordinates of several “checkpoints,” which Barlow prepared for us. Now we were on our own to plot the coordinates, decide the route, and drive it using the map and compass, just as we would do duirng the Rally. It seemed simple enough, but it would be the first time we were combining all the skills in a single exercise.

Making our way to the first “checkpoint” we realized it wasn’t that easy, even though there were marked trails (we had agreed to stay on legal trails for this exercise, respecting the rules of the public lands we were traversing). Barlow had chosen an area with a myriad of criss-cossing trails that added enough confusion to require us to be precise in our navigation.

Surrounded by all this incredible natural beauty, we had to look at the landscape differently, rather than being awestruck by redrock formations we focused on matching up terrain features to the map. As we stood beside our Jeep, map in hand, a tour Jeep full of visitors rumbled past. The driver thoughtfully stopped to ask us if we were lost. We thanked him, explained we were doing an exercise, and then as he drove off, we realized he HAD helped us, because the trail he came down was the path we were looking for!

We continued along until we were at the place we thought should be the first checkpoint. Barlow had called it a “water feature,” and looking around, we noticed a fence surrounding a large muddy puddle. I snapped a picture with my phone and sent it to her for confirmation. A few seconds later, we had an answer — we were correct. Feeling elated, we plotted the course for the next CP. We CAN do this!

MORE ON TRAINING: Tactical Driving & Expedition Management | Coal Country: Uncovering Forgotten Trails | Lessons from the Rubicon | Pathfinding Across Terra Incognita | Scouting the Sahara in Morocco | US Nomads Go to Jeep School | Learning to Read the Clues on a Map | Navigating the Desert the Bedouin Way | Route Finding with Orienteering

Barlow Jeep School is part of a suite of Jeep-related enterprises run by Nena Barlow under the Barlow Adventures brand. For over ten years, the Sedona-based program has offered regularly scheduled group courses as well as customized training regimes for corporate, military, industrial and private clients in Sedona, Moab, and most recently on the iconic Rubicon Trail.

Sedona is located in the Upper Sonoran desert of Northern Arizona. Straddling the county line between Coconino and Yavapai counties in the Verde Valley region, it is known for its amazing array of red rock formations. Visitors normally fly into Phoenix, then rent a car or take a shuttle for the two hour drive north.