In preparation for a longer upcoming trans-Saharan journey we conducted a scouting trip in Mauritania during January 2015. We spent roughly two weeks traversing 1,400 miles, mostly off-road, in a loop from the capital Nouakchott north along the coast to the border crossing near Nouadhibou then east to Choum and southeast via Chinguetti and Ouadane into the Eye of the Sahara (Geulb er Richat) and back around south west to Maaden through the White Valley to Azoueiga then Akjout and back to Nouakchott. The primary goal of this mission was to assess terrain, driving conditions, logistical concerns and approximate timeframes for a future expedition.

< BACK: ENROUTE IWIK TO NOUADHIBOU | MAURITANIA REPORT HOME

From Nouadhibou we turned back to the east, heading deeper into the desert along a piste that hugged the border following the rail line to Choum. We were leaving the heavily populated coastal area for the more desolate Saharan zone which makes up the northern two-thirds of the country. The landscape would become defined by empty stretches of soft sand and dunes alternating with granite outcroppings and spectacular ridgelines. We were entering the Sahara of postcards and popular imagination.

The piste started out as a clear avenue of well-worn tracks through solid sand, but as the sand got softer and the wind blew more of it into the air, traces became more difficult to find. The airborne dust turned the sky the same beige color as the sand in a monotone palette that seemed slightly foreboding. The horizon was blank. We looked to the train tracks to our north for guidance, but the flat steel rails at grade level were invisible from more than a few yards away.

The train seemed to materialize from nowhere like a mirage, suddenly kicking up a cloud of dust that moved along in a straight line growing larger until it revealed a bright blue and yellow engine, followed by another, and then an endless line of black hoppers full to the brim with chunks of iron ore. Rumbling across the Sahara at a top speed of about 30 miles an hour the SNIM train plays a pivotal role in Mauritania’s economy, moving massive quantities of iron from mines deep in the interior of the country to the port at Nouadhibou.

Metallic minerals are of considerable economic importance for Mauritania. In addition to the iron ore in the north, substantial amounts of copper are mined in the southwest, near Akjout. The mining and hydrocarbons industries accounted for approximately 75% of Mauritania’s export earnings and 30% of its fiscal revenue in 2013 according to the IMF, with iron ore, gold, petroleum and copper representing the largest shares as reported by The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

The presence of iron was first noted by French geologists in 1935, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that a group of French, British and Canadians figured out how to exploit it, forming the Société des Mines de Fer de Mauritanie (MIFERMA) to begin the process. The iron mine finally came on line in 1963, when the first trainload of ore left Zoureat for Nouidhibou where it was crushed, screened and blended, before being loaded onto ships for export.

The mining company was nationalized in 1974 as the Société Nationale Industrielle et Minière (SNIM), and operates mainly in the wilayas of Tiris Zemmour and Dakhlet Nouadhibou. According to the Financial Times, the state-owned company has grown to become the backbone of Mauritania’s economy. SNIM contributes roughly 25% of the national GDP, and thanks to a surge in iron ore prices over the past four years, the economy has improved markedly with an impressive 6.7% growth rate in 2014.

SNIM is one of the largest companies in Mauritania, and it’s iron train is the only train in the nation’s Mauritania Railway line, which consists of just this one 437-mile track running from Zouerate to the coast via Fderik and Choum. Reputed to be the longest in the world, the train sometimes reaches over a mile and a half in total length (2.5 kilometers). When fully configured, it has four in-line diesel-electric EMD locomotives plus 200 cars, each carrying up to 84 tons of iron ore. The iron train also carries passengers, and is something of an “attraction” for intrepid adventure tourists, as recounted in the New York Times.

Providing rudimentary public transportation across the harsh desert environment is just one way the mining company supports the population along the Zouerate – Nouadhibou corridor. With nearly 4,500 people on permanent contract and 10,500 employees overall, SNIM is the nation’s second-largest employer after the public sector. Perhaps more importantly, the company supplies basic services, like water and electricity, to local communities, and its non-profit foundation, created in 2007, has built and equipped health centers, schools, mosques, and wells for isolated rural villages.

Conditions for the rural population can be precarious. According to UNICEF, Mauritania continues to suffer from a multi-dimensional crisis related to food insecurity and a series of droughts that have compounded chronic poverty and undermined household resilience. The agency estimated that 531,000 people would require some kind of humanitarian assistance in 2014. Much of that assistance went to areas in the south, where already meager resources were stretched even thiner by the influx of Malian refugees. Here in the northern Adrar region most Mauritanians don’t count on getting outside help. Used to being self-sufficient, they adapt as best they can.

An elderly man we encountered reflected on the rapid societal changes he has seen during his lifetime. There used to be greater equality, he explained, while they may not have had the modern conveniences, people were on the same level. The majority were still pastoral nomads, moving from place to place with their herds according to the availability of water and plants for grazing. Others were small scale farmers, artisans or traders in the bigger towns. People would barter or sell what they produced to one another. There were few cars, and camels remained an important mode of transport for goods and people. There was almost no interaction with the “global economy.” The lifestyle was simple but everyone was in the same situation. Today, as modernization has increased the divide between the “well-off” urban population and those who have continued the traditional way of life, he has become relatively impoverished. Though he still has the milk and meat products from his livestock, the camels have less value compared to a truck. And the easy availability of modern manufactured goods reduces the market for handicrafts, so he and his family have less of value to sell, but must now pay more money to purchase their modern “needs.”

The situation is similar across the entire Sahara where pastoral nomadism was long the dominant lifestyle, but here in Mauritania it is more pronounced because a larger percentage of the population has continued the traditional lifestyle longer. In Mauritania nomads accounted for approximately 2/3rds of the population at independence in 1960, one third in 1977, and less than 6% by 2000, according to an OECD study. For comparison, in neighboring Mali they made up only 6% in 1960 and just 1% in 2009; in Algeria 10% at independence and less than 1% in 2008. So Mauritania’s society has experienced the most dramatic change, with those living the traditional lifestyle going from being a majority at independence to being a minority today.

Still, the desert heritage and respect for skills of the traditional nomads remain an integral aspect of modern Mauritanian identity. There is a sense of pride in the ability to master such a harsh environment, understanding the nuances of sand, dust and wind, a keenly developed situational awareness and expertise in land-marking, orienteering and tracking. Everyone here knows the desert can be very humbling.

We are roughly 120 miles west of Choum when the piste seems to disappear in the soft sand of the Azeffal dune field. There are no majestic high dunes here, just a 90-mile stretch of small sand dunes and tufts of half-buried vegetation that becomes increasingly more challenging to drive as the sand gets softer and the little dunes get tighter and closer together with more vegetation in between. From time to time there is an open flat section, but that too is very soft sand and we must keep up our momentum to avoid sinking down into it.

This is the route of the Africa Eco Race and the old Paris-Dakar. One of the most arduous off-road races in motorsports, the 14-stage Dakar Rally crossed the Sahara from its inaugural 1979 edition until the event was moved permanently to South America in 2008. The rally’s origin can be traced to 1977, when French motorcycle racer Thierry Sabine became lost in the Libyan Desert during a race from Abidjan to Nice. While waiting for rescue, he developed the idea of an annual rally through the challenging desert conditions, and upon his return to France began organizing the Paris-Dakar. The first edition was an epic 10,000 km journey across sand, rock, dunes, wadis, and swamps. Mauritania became a regular part of the route in 1986 and the Mauritanian stages of the race typically went through the Adrar region along the Zouerate – Choum – Atar axis. When security concerns in North Africa caused the Dakar to be moved, it was replaced by the Africa Eco Race, which has kept the tradition of the original Saharan desert rally running through Morocco, Mauritanian and Senegal. Though the 2015 Eco Race came through here just two weeks ago, their tracks were gone. Blowing sand can cover tire tracks and footprints in less than two hours, and with no clear piste to follow we just drove due east as straight as we could.

The sand was blowing a lot, and visibility was reduced as we came to a flat section of terrain that seemed to change texture, becoming more solid and slightly rocky. We could just see the outline of something big to our north, but the dust in the air made it difficult to define until we were practically right in front of it. The diffuse light created a dramatic reveal, turning Ben Amera into a surreal icon, it’s smooth black granite face rising up from the flat golden sand of the Sahara.

Depending on how you count it, Ben Amera is the world’s second or third largest monolith according to Touropia, and definitely the largest one in Africa (the first and second are both in Australia). A “monolith” is simply a geological feature consisting of a single massive stone or rock. In this case, a single piece of black granite that reaches a height of 1,300 feet hidden in the desert near the village of Tmeimichat. Undisturbed by mass tourism, Ben Amera sits in a barren landscape populated only with black-granite outcroppings. Each rock has a name, and locals point out “Aisha,” as Ben Amera’s “wife.” At its base a herd of goats search for pasture, while their owner looks on. We are the only ones here and can take some time to explore this strange series of monoliths before continuing on to Choum.

Beyond Ben Amera the piste is visible again, and the terrain gets easier as we approach Choum. A dusty rough and tumble town very close to the border with Western Sahara, Choum straddles what was once a major camel caravan route across the Sahara. The caravans traveled along a string of reliable wells, avoiding the more difficult terrain in the mountains and great seas of sand dunes. Choum was one of a number of small ‘supply stations’ that grew up along the busy north-south route connecting the civilizations of riverine West Africa in the south with the great population centers of the Atlas Mountains in the north. Even after the disappearance of the fabled caravans carrying gold from the Bambuk goldfields to Fez and Marrakesh, smaller more mundane trade caravans continued to use this route well into the 1950s. The importance of the settlement declined with that trade, and the town, with a population of around 5,000, is now simply a stop on the Iron Ore train.

Apart from a few brightly painted store fronts, the town is the color of the earth, mostly made up of low flat-roofed mud brick buildings strung out across the desert. In the distance we can see the beginning of the mountains that will define the landscape in the Adrar region. The sleepy town seemed as faded and forgotten as the stories of ancient camel caravans. In more recent times, it’s only claim to fame is as a footnote in the history of the Western Sahara conflict. The war had been going badly for Mauritania, the Polisario had succeeded in attacking Nouakchott and in December of 1977 the government asked France for military assistance. The French military suspected Choum to be a base for Polisario forces, and they sent a a few of their Jaguar Jets to bomb and strafe the town and nearby Polisario positions in an attempt to drive the guerrillas out. There is little on record beyond that, and the war went on until Mauritania withdrew and the frontiers went back to the lines drawn in colonial times. But the town’s position so close to the border makes it likely that the sympathies and trading patterns of residents take the Sahrawis into account.

At the “crossroads” of the piste from Nouadhibou to the west and the north-south Zouerate-Atar route, Choum still serves as something of a re-supply point for overland travelers. It is possible — though quite expensive — to get gas here, as well as other necessities like basic food and bottled water. The piste from the west leads directly into the market area in the center of town near the mosque. Street vendors come up to the truck to sell bread and other staples, but otherwise there is little activity. Despite the fact that the Iron Ore train makes a passenger stop here, it is not a very touristic town. Other than a few shopkeepers chatting among themselves, the streets seem oddly deserted. To the east, the flat desert is broken up by rocky ridges and cliffs that run southwest longitudinally bisecting the arid plains. Beyond them is a mass of dunes. The old caravan traders had very wisely chosen this side as the most hospitable north-south route, and we would follow their path south from here.

WHERE WE ARE

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania is the eleventh largest country in Africa. Although the country is mostly desert (90% of the land is within the Sahara), it has 468 miles of Atlantic coastline. It is roughly three times the size of New Mexico. Most of the population is concentrated in the coastal cities of Nouakchott and Nouadhibou and along the Senegal river in the southern part of the country. The nation shares borders with Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, Algeria, Mali, and Senegal. The official language is Arabic, though the regional dialect is Hassaniya, and many people also speak French (Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960).

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

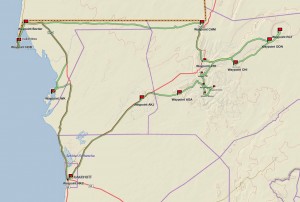

NOUADHIBOU / CHOUM – 300 miles – Estimated drive time 9 hours

(Click map for larger view of route. Red is current segment. Blue is cumulative route.)

From Nouadhibou, we take the tar road north, then east, back past the border turnoff. Near the intersection with the N1, we pick up a sandy piste heading due east parallel to the railroad tracks for about 235 miles to Choum. The piste is flat, but at points becomes very soft sand and gets trickier to drive, notably in the Azeffal dunes. Navigation gets harder too, because tire tracks disappear in this kind of sand, making it difficult to find the route. The key is to just keep heading due east, as it is entirely flat until the rock formation known as Ben Amr, and from there the sand gets a bit more solid again. Though it is possible to drive it in one long day, we will do it in two, camping en route to break up the drive.

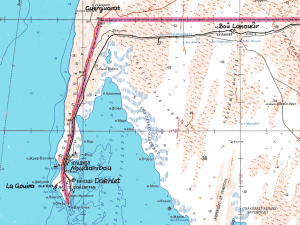

TERRAIN DETAIL: NOUADHIBOU

Situated on a 65-kilometre long peninsula that is only 13 kilometers wide, Nouadhibou and its near environs are primarily flat and sandy desert. There are steep rocky cliffs looking down to the sea at Cap Blanc, and the terrain is a bit rockier in parts. Battering surf and shifting sand banks characterize the entire length of the Atlantic shoreline.

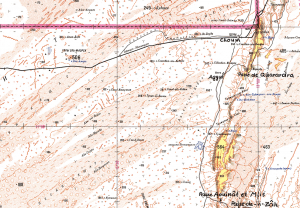

TERRAIN DETAIL: CHOUM

The town is on the edge of the flat sandy desert where it meets the reg, or rocky area, at the base of a mountainous ridge line that runs north-south. Coming from the west the terrain is soft sand, and mostly flat, though there is a challenging patch for about 90 miles across the Azeffal dunes, which is a seemingly endless field of low small sand dunes interspersed with tufts of camel grass that makes it difficult to drive a straight line. Heading south, the terrain changes markedly with alternating sections of rock and sand.

MINERALS IN MAURITANIA

Mauritania was the second ranked producer of iron ore in Africa after South Africa in 2011, and the world’s 15th ranked producer in terms of the tonnage, according to a USGS report. The country’s geology provides a wealth of different mineral deposits in each of four separate geological zones. The major iron and gold deposits are in the Reguibat shield in the north which includes the Archean rocks and the Paleoproterozoic Birimian succession. In the south-central region, the Mauritanides belt includes the important Guleb Moghrein copper-gold deposit. Phosphate rock and petroleum can be found in the Paleozoic to Cenozoic sedimentary formations of the coastal basin. The east-central region has the Taoudeni basin, one of the largest Proterozoic to Paleozoic sedimentary formations in Africa, which contains base-metal mineralization.

LANDMINE DANGERS

According to the US State Department’s Safety and Security briefing for Mauritania, “landmines remain a danger along the border with the Western Sahara and travelers should cross only at designated border posts.” Though there have been demining operations, and no recent reports of injuries, it is still advisable to stay south of the train tracks along the border area. Knowledgable observers say there are areas that have not yet been entirely cleared of mines and suggest that visitors only cross the tracks if they are with a local person who knows the area very well. The last reported landmine incident near Nouadhibou was in 2009, according to Sahara Overland. For more detail on the disposition of the landmines see these rough maps.

DRIVING IN SAND

Driving in the deep soft sand of the Sahara takes practice and even local drivers get stuck. However, there are a few principles that will make it easier to get through this terrain. Lowering tire pressure increases the “footprint” — the part of the tire track that has contact with the ground — and is key to improving traction. Local drivers play with the nuances of tire pressure and can often get “unstuck” simply by airing down a little more. When driving in sand, make smooth and subtle changes. Start off with wheels straight and slowly accelerate to gain momentum. Likewise, coast to a stop rather than using the brake. Make turns as wide as possible, and avoid the softest sand at the base of dunes and wadis. NOTE: It is recommended that drivers without significant desert experience do not attempt these routes on their own, unless someone in the group has previously driven off-road in the Sahara or has had appropriate professional training.

CURRENT WEATHER

Details: Nouadhibou | Choum

THE SAHARA IN MAURITANIA

Terrain: In the western portion of the Saharan Zone, extending toward Nouakchott, rows of sand dunes are aligned from northeast to southwest in ridges from two to twenty kilometers wide. Between these ridges are depressions filled with limestone and clayey sand capable of supporting vegetation after a rain. Dunes in the far north shift with the wind more than those in the south. The regions of Tiris Zemmour, Adrar and Hodh ech Chargui are vast empty stretches of dunes alternating with granite outcroppings. After a rain, or in the presence of a well, these outcroppings may support vegetation. The plateaus of Adrar and Tagant, where springs and wells provide water for pasturage and some agriculture, can be lush.

Weather: Temperature fluctuation during the day can be extreme. In December and January, temperatures go from morning lows of 32°F/0°C to afternoon highs of 100°F/38°C. In the hottest summer months highs typically reach 120°F/49°C. Throughout the year, the harmattan (a dry, dusty easterly or northeasterly wind on the West African coast) often causes blinding sandstorms. Rain typically falls during the “hivernage” (July to September) when isolated storms drop large amounts of water in short periods of time. However, a year, or even several years, may pass without any rain in some locations.

Vegetation: In mountainous areas with a water source there are small-leafed and spiny plants and scrub grasses suitable for camels. Dunes sprout sparse vegetation after a rain (the seeds of desert plants can remain dormant for many years). In depressions between dunes, where the water is nearer the surface, some flora–including acacias, soapberry trees, capers, and swallowwort–may be found. Saline areas have a different kind of vegetation, mainly chenopods, which are adapted to high salt concentrations in the soil. Cultivation is limited to oases, where date palms are used to shade other crops from the sun.

THE COMPLETE ROUTE

(click map for larger view of route)

Waypoint: Nouakchott

Drive: Nouakchott to Iwik

Waypoint: Iwik

Drive: Iwik to Nouadhibou

Waypoint: the Border

Waypoint: Nouadhibou

Waypoint: Cap Blanc

Drive: Nouadhibou to Choum

Waypoint: desert piste

Waypoint: Ben Amara

Waypoint: Choum

Drive: Choum to Ouadane

Waypoint: Atar

Waypoint: Ouadane

Drive: Ouadane to Richat

Waypoint: Richat

Drive: Richat to Chinguetti

Waypoint: dunes

Waypoint: Chinguetti

Drive: Chinguetti to Tergit

Waypoint: Tergit

Drive: Tergit to Maaden

Waypoint: desert oases

Drive: Maaden to Azoueiga

Waypoint: White Valley

Waypoint: Azoueiga

Drive: Azoueiga to Nouakchott

Waypoint: Akjout

Waypoint: Nouakchott

ABOUT THE TRUCK

Our journey was made in a locally-sourced diesel powered 2010 Toyota HiLux with Dunlop Sand Grip tires. The HiLux is one of the most common trucks seen on the pistes in Mauritania and is relied on by drivers here. Though not available in the U.S. market, over 13 million Toyota Hilux have blazed trails around the world since 1968. From the Arctic to the Sahara, this unstoppable pick up has earned trust and admiration for its off-road capabilities and endurance.

NOMADS AND URBANIZATION

Mauritania’s population underwent dramatic change as a consequence of the droughts of the 1970s, moving away from their traditional lifestyles as pastoral nomads or sedentary agriculturists. According to the U.S. Library of Congress Country Study, 90 percent of the population were living traditional lifestyles dispersed across the countryside in the 1960s. The percentage of the population that was still nomadic or seminomadic dropped to less than 25 percent by the mid-1980s. While many factors contributed to this shift, including long-term efforts by colonial and independent governments to settle the nomads and new employment opportunities associated with mining and export industries, the droughts and resultant desertification of the land were paramount. Counting both resident and temporary urban dwellers, some sources in the late 1980s placed Mauritania’s urban population at or above 80 percent.

ENDLESS DESERT

Though the Sahara is not actually the world’s largest desert (Antartica is), it is massive — and is increasing in size every year due to desertification. According to the Conservation Institute, the Sahara now comprises eight percent of the world’s land area — one could place the entire continental U.S. within the Sahara and still have a few thousand square miles of desert left over. However, despite it’s size, it is not very populated. The U.S. is home to 300 million individuals, while the Sahara counts just two million inhabitants. That’s a population density of only 1/150th of the U.S.

NOTE: This is the fourth in a series of segments highlighting details of our Mauritanian scouting misson. Each segment will focus on a specific location or region. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in January 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads supported by a local Mauritanian crew. For more information about the team or the specifics contact us.