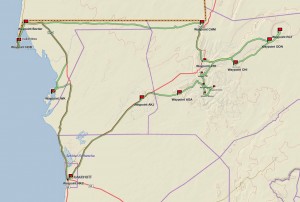

In preparation for a longer upcoming trans-Saharan journey we conducted a scouting trip in Mauritania during January 2015. We spent roughly two weeks traversing 1,400 miles, mostly off-road, in a loop from the capital Nouakchott north along the coast to the border crossing near Nouadhibou then east to Choum and southeast via Chinguetti and Ouadane into the Eye of the Sahara (Geulb er Richat) and back around south west to Maaden through the White Valley to Azoueiga then Akjout and back to Nouakchott. The primary goal of this mission was to assess terrain, driving conditions, logistical concerns and approximate timeframes for a future expedition.

< BACK: ENROUTE NOUAKCHOTT TO IWIK | MAURITANIA REPORT HOME | AHEAD: ENROUTE NOUADHIBOU TO CHOUM >

Heading north from Iwik towards Nouadhibou, we are on a well used piste across flat open desert and can move at a good pace. The horizon is completely featureless for a long stretch, and we simply navigate using the general north-northwest direction in a straight line for roughly 45 miles to intercept the tar road. The sand itself seems to change character as we cross it, morphing from beach sand to coarse sand to dried mud-like sand to solid packed sand, then back to soft sand blowing across the flat desert tracks. Eventually we note some small rises on the edge of the horizon, and as we get closer we can match them up to corresponding features on the topo map indicating our approach to the N2.

The tar road seemed to appear out of nowhere. The total flatness of the terrain, combined with little vehicular traffic, made it hard to see until we were practically on it. The wind was picking up. Ribbons of sand were blowing across the road and the blue sky began to have a beige tint.

Wind and blowing sand are constants everywhere in the Sahara. This whole region is subject to the Harmattan, a dry and dusty trade wind blowing continually from the northeast between a subtropical high-pressure cell and an equatorial low-pressure cell. As air moves downward from the high-pressure into the low-pressure cell, it becomes hotter and drier creating scorching duststorms. Even when there isn’t a dust storm, this wind carries fine particles of sand suspended in the air forming a cloudy screen that makes it difficult to see ahead. Sometimes a heavy amount of dust in the air can severely limit visibility and block the sun for several days. Known as the Harmattan haze, the fog-like effect costs airlines millions of dollars in cancelled and diverted flights each year. However, when the haze effect is weak, this dry wind creates visually stunning diffused lighting that seems to render the landscape in slightly blurry pastels.

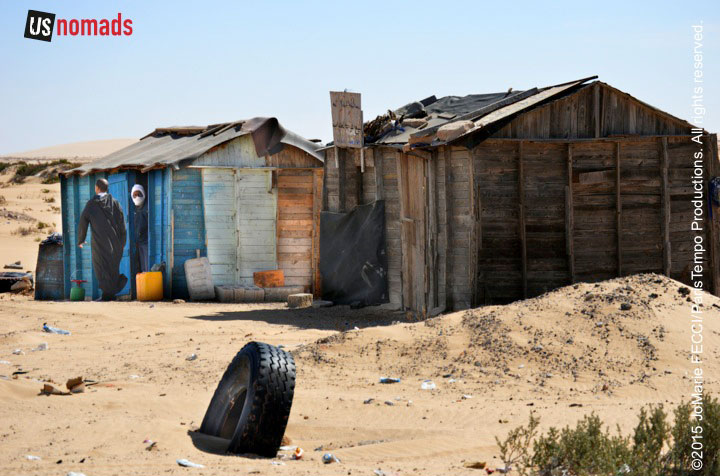

The desert looked desolate and inhospitable as we turned westward back towards the coast near Bou Lanouar. On the outskirts of the town some of the wooden buildings were so windblown they literally tilted, adding an element of surreality to the barren landscape. We were now driving parallel to the railroad tracks and the border with Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara. Morocco was just beyond. There is only one official overland border crossing here, and travelers are advised not to go north of the train tracks at any other spot because of the continued presence of unmarked landmines.

An unfortunate legacy of the Western Sahara conflict, the mines were placed primarily around urban centres and key economic targets by Mauritania, Morocco and the Polisario in the late 1970s. A variety of mine types are present in Mauritania, although the Journal of Mine Action says the most common are the French APID 51 (anti-personnel) and ACID 51 (anti-tank). As of 2007, at least 60 communities remained affected by mines with the greatest dangers from the larger mine fields near Nouadhibou and Bir Mohgrein, according to an IRIN report on the mine mapping survey conducted by the UNDP and Mauritania’s national demining agency.

Though the country has taken steps to reduce the impact of mines with help from international organizations, removal has been complicated because the mines were placed without being marked or documented. Many landmines lie covered by dunes that are constantly shifting, which physically moves the mines from one location to another or buries them so deeply that mine detectors may not find them. Without records, the demining is slow and remains incomplete.

Beyond Bou Lanouar the turnoff for the border post is deserted. Coming in overland from Morocco and Western Sahara this is where we would arrive after a straightforward crossing over a 3km no-man’s-land that separates the two border posts. Diplomatically, a sign simply says “Dakhla,” the name of the next major town in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, thus avoiding any political tangle over an overt mention of either Morocco or Western Sahara.

The messy end of the colonial period in Africa has left many complications on the continent, and this corner of Mauritania butts up against one of them — the status of “Western Sahara.”

Prior to decolonization, the territory of Mauritania was part of “French West Africa” and the territory of Western Sahara was known as “Spanish Sahara.” Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960, but Spain held on to their colony until 1975. When the Spanish finally left, Morocco and Mauritania annexed the territory against the wishes of many of the Sahrawi people living there who wanted their own independent nation. The Sahrawis’ liberation movement, the Polisario, with support from Algeria, took up arms against the Moroccans and Mauritanians, successfully pushing Mauritania out of their territory in 1979.

The war between Polisario and Morocco continued for 16 years leading to a stalemate and eventually a ceasefire in the early 1990s. Roughly 80% of the territory remains under Moroccan control, the other 20% is controlled by Polisaro forces as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, an independent state that has been reconginzed by 84 other nations, though it has not yet been admitted to the UN. The UN still considers Western Sahara a “territory that needs to express its wishes with respect to statehood.” A referendum is supposed to be held under UN auspices, to determine whether or not the indigenous Sahrawis wish to be independent, as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), or to be part of Morocco. However, the Moroccan government has continually blocked such a referendum.

Mauritania “recognized” SADR in 1984, but does not have “diplomatic relations” with it, and has since stayed out of the territorial dispute with an official position stating that Mauritania wishes for an expedient solution that is mutually agreeable to all parties.

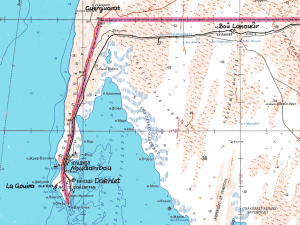

From the border turnoff we continued west, until we could see the water of the Baie du Lévrier peeking out from behind the desert sand. The Ras Nouadhibou peninsula is also a “shared” territory administratively divided between Western Sahara and Mauritania. The eastern shore, with the port and railhead belong to Mauritania, while on the western side, the city of La Güera is part of Western Sahara. As we approached the edge of the urban area, the frequency of checkpoints increased again, with an additional one manned by the security forces related to the railroad train that brings iron ore to port. Traffic bottle-necked and progress was slow.

The name “Nouadhibou” means “place of the jackal” and it is said that many jackals used to come here to drink from a local well, but the city was called Port-Étienne under the French. It is the second largest city in Mauritania and serves as a major commercial center. The peninsula on which it sits is roughly 50 kilometers long and 13 kilometers wide, separating the Atlantic from the bay. One of the largest natural harbors on the west coast of Africa, the Baie du Lévrier was highly valued by French merchants for the protection it offered ships from the harsh waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The merchants settled on the eastern side of the peninsula and built up a large shipping trade, which the Mauritanians have expanded on.

In marked contrast to the emptiness of the surrounding desert, Nouadhibou is bustling with activity. It has the ambiance of a frontier town abuzz with transactions and intrigue. Traders from Russia, China, France and Spain make deals with local businessmen. Locals sell and trade with each other. In the shadows other kinds of business is conducted. Nouadhibou is reported to be a favorite point of departure for African migrants trying to make their way to Europe via the Canary Islands. According to The Economist, the would-be migrants pay large fees to get aboard small fishing boats and make the dangerous 800 kilometer crossing to the Canaries.

Nouadhibou is also said to be a center for the illegal trading of meteorites found in the Sahara, the BBC reports. Some of the rarest rocks on earth land from space in the remotest parts of the desert. Many Mauritanian nomads know they have value, and go searching for them, then bring them to the market traders here. The meteorites are sold to foreign collectors who smuggle them out of the country.

Beyond the crowded center, the port itself sprawls south along the peninsula, where the terrain becomes layered rocky shelf mixed with soft sand. The tar road ends and we pick up a rough piste all the way to the southern most tip. Container ships are anchored off shore, and small motorized pirogues weave in between. Though Nouadhibou is supposed to be one of the world’s biggest ship graveyards, we don’t see much evidence of that. It seems the earlier practice of just abandoning the ships off-shore has been replaced by a more organized salvage process, with local enterprises methodically stripping the vessels for valuable parts.

The entrance gate to the Cap Blanc reserve was padlocked, but a well used bypass ran next to it, going past an old lighthouse compound. According to the Lighthouse Directory Index, it was without a lantern for many years, but a Spanish company, La Maquinista Valenciana restored it in 2009. It is very near to the international border, and the area is under military surveillance, but we were permitted to drive almost to the end of the promontory. Continuing the last bit on foot, we carefully made our way to the southern most point, where the heights dropped dramatically over the crest of a dune straight down onto the rocks below as the sea came crashing in rhythmically over and over again.

< BACK: ENROUTE NOUAKCHOTT TO IWIK | MAURITANIA REPORT HOME | AHEAD: ENROUTE NOUADHIBOU TO CHOUM >

WHERE WE ARE

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania is the eleventh largest country in Africa. Although the country is mostly desert (90% of the land is within the Sahara), it has 468 miles of Atlantic coastline. It is roughly three times the size of New Mexico. Most of the population is concentrated in the coastal cities of Nouakchott and Nouadhibou and along the Senegal river in the southern part of the country. The nation shares borders with Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, Algeria, Mali, and Senegal. The official language is Arabic, though the regional dialect is Hassaniya, and many people also speak French (Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960).

ABOUT THE DAY’S ROUTE

IWIK / NOUADHIBOU – 180 miles – Estimated drive time 4 hours

(Click map for larger view of route. Red is current segment. Blue is cumulative route.)

Leaving Iwik, we take the piste across the desert north-east to intercept the tar road the rest of the way to Nouadhibou. The day’s drive of roughly 180 miles should not be difficult. The only challenge will be navigation across the featureless section of desert from Iwik to the road. Once on the tar road, we will head north to Bou Lanouar, which is just below the border, then west along the border back towards the coast. We will pass the turnoff to Dakhla, which is the official border-crossing into Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara and Morocco, then continue on, turning south down the peninsula all the way to Cap Blanc at the very tip.

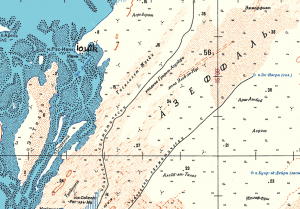

TERRAIN DETAIL: IWIK

The village is located on the shore of a peninsula in the Banc D’Arguin. The surrounding area is primarily flat and includes sandy beach, mudflats, and sandy desert.

TERRAIN DETAIL: NOUADHIBOU

Situated on a 65-kilometre long peninsula that is only 13 kilometers wide, Nouadhibou and its near environs are primarily flat and sandy desert. There are steep rocky cliffs looking down to the sea at Cap Blanc, and the terrain is a bit rockier in parts. Battering surf and shifting sand banks characterize the entire length of the Atlantic shoreline.

LANDMINE DANGERS

According to the US State Department’s Safety and Security briefing for Mauritania, “landmines remain a danger along the border with the Western Sahara and travelers should cross only at designated border posts.” Though there have been demining operations, and no recent reports of injuries, it is still advisable to stay south of the train tracks along the border area. Knowledgable observers say there are areas that have not yet been entirely cleared of mines and suggest that visitors only cross the tracks if they are with a local person who knows the area very well. The last reported landmine incident near Nouadhibou was in 2009, according to Sahara Overland. For more detail on the disposition of the landmines see these rough maps.

THE HARMATTAN

The Harmattan is a cold-dry and dusty trade wind, blowing over the West African subregion. This northeasterly wind blows from the Sahara Desert into the Gulf of Guinea between the end of November and the middle of March, during the dry season. The Harmattan lowers humidity, dissipates cloud cover, prevents rainfall formation and sometimes creates big clouds of dust or sandstorms. The dust travels hundreds of kilometers out over the Atlantic Ocean, interfering with aircraft operations and settling on the decks of ships.

CURRENT WEATHER

Details: Nouakchott | Nouadhibou

THE SAHARA IN MAURITANIA

Terrain: In the western portion of the Saharan Zone, extending toward Nouakchott, rows of sand dunes are aligned from northeast to southwest in ridges from two to twenty kilometers wide. Between these ridges are depressions filled with limestone and clayey sand capable of supporting vegetation after a rain. Dunes in the far north shift with the wind more than those in the south. The regions of Tiris Zemmour, Adrar and Hodh ech Chargui are vast empty stretches of dunes alternating with granite outcroppings. After a rain, or in the presence of a well, these outcroppings may support vegetation. The plateaus of Adrar and Tagant, where springs and wells provide water for pasturage and some agriculture, can be lush.

Weather: Temperature fluctuation during the day can be extreme. In December and January, temperatures go from morning lows of 32°F/0°C to afternoon highs of 100°F/38°C. In the hottest summer months highs typically reach 120°F/49°C. Throughout the year, the harmattan (a dry, dusty easterly or northeasterly wind on the West African coast) often causes blinding sandstorms. Rain typically falls during the “hivernage” (July to September) when isolated storms drop large amounts of water in short periods of time. However, a year, or even several years, may pass without any rain in some locations.

Vegetation: In mountainous areas with a water source there are small-leafed and spiny plants and scrub grasses suitable for camels. Dunes sprout sparse vegetation after a rain (the seeds of desert plants can remain dormant for many years). In depressions between dunes, where the water is nearer the surface, some flora–including acacias, soapberry trees, capers, and swallowwort–may be found. Saline areas have a different kind of vegetation, mainly chenopods, which are adapted to high salt concentrations in the soil. Cultivation is limited to oases, where date palms are used to shade other crops from the sun.

THE COMPLETE ROUTE

(click map for larger view of route)

Waypoint: Nouakchott

Drive: Nouakchott to Iwik

Waypoint: Iwik

Drive: Iwik to Nouadhibou

Waypoint: the Border

Waypoint: Nouadhibou

Waypoint: Cap Blanc

Drive: Nouadhibou to Choum

Waypoint: desert piste

Waypoint: Ben Amara

Waypoint: Choum

Drive: Choum to Ouadane

Waypoint: Atar

Waypoint: Ouadane

Drive: Ouadane to Richat

Waypoint: Richat

Drive: Richat to Chinguetti

Waypoint: dunes

Waypoint: Chinguetti

Drive: Chinguetti to Tergit

Waypoint: Tergit

Drive: Tergit to Maaden

Waypoint: desert oases

Drive: Maaden to Azoueiga

Waypoint: White Valley

Waypoint: Azoueiga

Drive: Azoueiga to Nouakchott

Waypoint: Akjout

Waypoint: Nouakchott

ABOUT THE TRUCK

Our journey was made in a locally-sourced diesel powered 2010 Toyota HiLux with Dunlop Sand Grip tires. The HiLux is one of the most common trucks seen on the pistes in Mauritania and is relied on by drivers here. Though not available in the U.S. market, over 13 million Toyota Hilux have blazed trails around the world since 1968. From the Arctic to the Sahara, this unstoppable pick up has earned trust and admiration for its off-road capabilities and endurance.

SAHARA DUST & THE AMAZON

Dust from the hot Saharan desert may have a connection to a totally different climate in South America, according to a NASA study. The plumes of dust can sometimes be seen on satellite images when they first emanate from Africa, on their way westward to parts of the Caribbean Islands and South America. This dust provides much needed phosphorous to the soil of the Amazon acting as fertilizer for the rainforest. Approximately 22,000 tons of phosphorous reach the Amazon every year from the Sahara nearly 1,600 miles away.

THE ATLANTIC COAST

Mauritania’s coastal zone consists of roughly 469 miles along the long Atlantic. Prevailing oceanic trade winds from the Canary Islands modify the influence of the dry dusty wind known as the “harmattan” and temperatures are moderate. Battering surf and shifting sand banks characterize the entire length of the shoreline. Much of the coastal zone is encompassed within the Banc D’Arguin national park, which extends from Cap Timiris in the south, includes the Ile de Tidra, Ile d’Arguin and Cap d’Arguin to Pointe Minou in the north. The park’s boundary extends a maximum of 60km into the shallow sea and inland by 35km into the Sahara desert. The contrast between the harsh desert environment and the biodiversity of the marine zone has resulted in a land- and seascape of outstanding natural significance. The protected conservation area is considered unsuitable for large-scale tourism, there are no hotels or restaurants, and drinking water is not available. Visitors can obtain authorization to enter the park on an individual basis from the park administration.

THE SAHARA’S SAND

Desert sand is actually composed of finely divided rock and mineral particles. Defined by size, “sand” is finer than gravel and coarser than silt. The most common type of sand is silica, usually fragmented quartz, and the second most common is calcium carbonate (main component of limestone) made from the accumulated remains of shellfish and coral over millions of years. The composition of the sand will determine its color. For example, beaches in southern Europe are a deep yellow color caused by the imperfections in the quartz. Tropical white sandy beaches are the result of eroded limestone and, sometimes, crushed coral and shellfish. Sand derived from volcanic rocks (like obsidian) is black. The Sahara desert sand is primarily quartz (most sand is) but also contains mica, amphibole, calcite, ankerite, feldspar (both K-spar and plagioclase), dolomite and less common minerals such as nitratine and halite. For more on the composition of Sahara sand see this report on the chemistry of Sahara’s sand dunes.

NOTE: This is the third in a series of segments highlighting details of our Mauritanian scouting misson. Each segment will focus on a specific location or region. All text and photos are copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted. If you would like to use any imagery here, please contact us for permission. The trip was conducted in January 2015 by JoMarie Fecci of US Nomads supported by a local Mauritanian crew. For more information about the team or the specifics contact us.