Not all “deserts” are the same. That sounds pretty obvious, but as we’ve become more comfortable with “desert driving” in general, we started to note some nuances in approach both to the terrain and to navigating with maps. Things that work well in the Sahara are not necessarily relevant in the American southwest, or the Gobi. What follows are a few random thoughts in no particular order about the peculiarities of each.

All deserts are “vast” almost by definition, so let’s talk about “relative” vastness. The Sahara is huge. At 3.5 million square miles it is almost as big as the entire United States, so distances there can be very long and we speak in “days” of travel–as in “how many days journey is it to…” The Gobi spans across 500,000 square miles and is almost as big as Alaska. Comparing the deserts of the American southwest is complicated because there are actually four different somewhat contiguous “deserts” that come together like a jigsaw puzzle. Separately they are all smaller than the Gobi, but taken together as a region including the continuation into Mexico, they are quite large. The Mojave Desert can be found in the southwestern United States covering portions of southern Nevada and southeastern California. The Mojave Desert contains the infamous Death Valley, known for being the lowest point, driest location, and hottest area on the North American continent. It is roughly 50,000 square miles and is bounded on the north by the Great Basin desert and on the south by the Sonoran desert. The Sonoran Desert, with over 100,000 square miles, covers large parts of the Southwestern United States in Arizona and California, and of Northwestern Mexico in Sonora, Baja California and Baja California Sur. It is the hottest desert in North America. The Chihuahuan Desert is the largest desert in the North American continent. It has a land area of over 390,000 square miles with 30% in the southern United States (parts of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico) and 70% in Northern Mexico (Chihuahua, Durango, Coahuila, Zacatecas, and Nuevo Leon). The Great Basin Desert is the largest desert in the United States occupying approximately 190,000 square miles and is, like the Gobi, a “cold” desert. The Great Basin desert borders the Sierra Nevada Range on the west and the Rocky Mountains to the east, and to the south are the Mojave and Sonoran deserts.

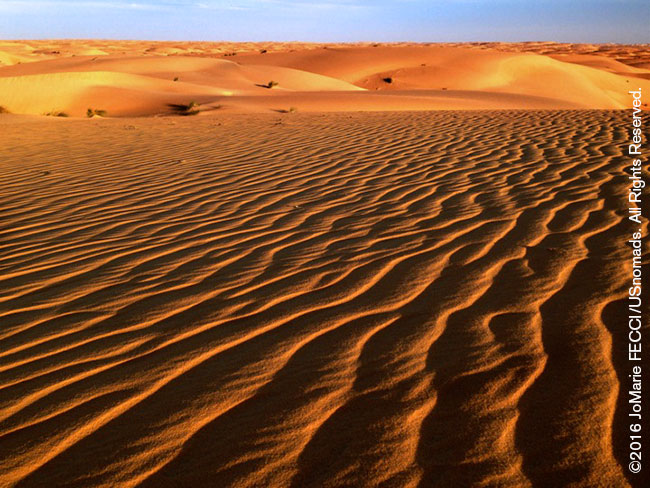

The Sahara is by far the “sandiest” of the three regions, with the most soft sand and large seas of sand dunes in many places. Though it has plenty of rocky areas, too. It is a desert of extremes and has the biggest dunes, the largest dune-fields and the largest distances between water sources. The Gobi is a rocky desert, with lots of gravelly dirt, and only a few sand dune seas. It is a desert of the “spectacular,” with some of the most breathtaking vistas anywhere. The southwest of the USA has the most varied terrain types including incredible canyons, sand dunes, colorful rock formations, and otherworldly landscapes. In terms of driving terrain it has it all.

The biggest difference between driving “on dirt” in these locations is that most of the trails in the US southwest are “recreational” and managed, where as in the Sahara and the Gobi, they are roads (or at least general routes) that people use to get from one place to another, and there is no “management” of these “roads” for the most part.

US southwest: Because most “off-pavement” driving is strictly regulated in the United States and public land is managed by different agencies, it is important to know which “trails” you can and cannot drive on. Just because it exists on a map, doesn’t necessarily mean you can legally access it (and in a lot of cases you need to obtain a specific permit in advance). Legal trails are clearly marked and mapped and drivers must remain on designated trails and cannot just take off into the desert on a general heading.

For conservation purposes (and in order to prevent trail closures) it is important to always stay on the trail and not make it wider or create a new by-pass around an “obstacle.” All drivers should follow the Tread Lightly practices. Most of the legal trails here are used for “recreational” purposes, which can be divided into basically two categories: “access” routes and “fun” trails. Access routes are dirt roads that “go” someplace, like to a lake, a great camping area, a hiking trailhead, a working mine, etc. They are usually fairly well-graded and somewhat maintained, and are very easy to drive on, though they can get quite “washboarded.” In contrast, “fun” trails can range from easy to near-impossible to drive. These are trails used specifically for challenging off-road driving with different levels and types of obstacles that are often not passable for un-modified vehicles. The difficulty level of these trails is not indicated on a map, so it is important to research your routes while planning to make sure your vehicle will be appropriate for the conditions.

The Sahara and the Gobi: The “trails” or “pistes” here are often the only roads and they are used primarily to get from one place to another, not as “recreation,” hence well-used existing trails will almost always take the easiest route. People drive these routes in all kinds of vehicles, with all kinds of tires, so a well equipped 4-wheel drive vehicle should not face anything too challenging as long as you keep to well-used tracks.

Sometimes knowing where the “road” is can be a bit complicated, as hundreds of parallel tracks weave in and out spreading the whole width of the visible desert. If you look carefully, you will probably notice they all go in generally the same direction. This is the local old-school version of a “superhighway” and you just need to know which direction you want to go and can pretty much follow any of the sets of tracks that go that way. What is important is to make sure you don’t veer off too much to one side or the other from your general heading. It is usually good to pick a terrain feature in the distance as a “target” to aim for to stay in rough line with your heading as you drive.

In much of the Sahara there are no restrictions about where you can drive, and people often take “cross-country” (meaning off-trail) short cuts. If you are unfamiliar with the topography of an area, be very careful doing this. Existing routes were chosen for a reason by local drivers who know the terrain — they are usually the best way to go (sometimes for physical terrain reasons, and sometimes for security reasons). The Gobi is similar in this respect to the Sahara, though there is more of a tendency to stay on existing tracks than in the Sahara, which leads to extremely washboarded roads.

Map resources and the differences between what is on the map and what is actually on the ground in front of you vary hugely. The US southwest is well mapped and regulated. The Sahara and the Gobi are not.

US southwest: Just because it is well-mapped, however, doesn’t mean that the map and the ground in front of you will always match up. Your map will indicate “legal” trails but not necessarily “all” trails or old roads or private mining company roads, meaning there might be trails you see that don’t appear on the map. And if the map is not current, there might be trails that appear on it that no longer exist.

It’s also a good idea to know where a trail goes before you take it. One unique thing about trails here is that they sometimes don’t actually “go” anywhere. Because some of these are “recreational” trails they may only be a loop around some “fun” obstacles (that might not be fun for you). In other cases they were old mining roads that go someplace where there once was a mine (sometimes there are traces of the old mines, and sometimes there aren’t — and exploring around old mines can be very dangerous). In fact, another interesting detail about driving on dirt in the US southwest, is that no one lives there. For the most part these trails go across “public land” which is National Park, National Monument, National Forest, Bureau of Land Management or some kind of state or local authority — but they do not include towns or villages or many residences at all. It means you cannot count on running into “the local people” to ask direction or advice. If you encounter other people, they will likely be other recreational drivers, hikers, bikers, campers, park rangers or possibly permitted mining or logging personnel. These folks may or may not know the area. On the plus side, most of these “public lands” are defined areas bounded by paved roads between towns (and even big cities) with access to supplies, gas, and other necessities. So even though much of it is seems very remote, “civilization” is never really that far away should you need it.

The Sahara: there are various map sets available for the Sahara, and the traditional main overland routes are well-known. The pistes on the map will most likely exist (though depending on the date of the map, it is possible that there are new pistes and/or actual paved road replacing an old piste). Depending on the type of terrain the turnoff for pistes may not be easy to see. In very soft and blowing sand the tracks get covered and it is sometimes very difficult to determine the route. However, most routes connect places where people live, so you will often encounter local drivers or nomads along the way. It is always a good idea to get updated information from anyone you encounter about the conditions on the road ahead as well as any kind of security issues or police or military actions. Locals will also be able to help you if you are unsure of the way, but in more remote areas do not expect them to be able to indicate directions on your map — while some people (especially drivers) will be familiar with the maps, the traditional way of giving directions is with reference to landmarks and length of journey in time not distance. So directions might be something like this: “continue east for half a day and you will pass a grassy area, and then a large wadi, cross the wadi and look for the flat black mountain, in the shadow of the mountain there is a village near a well…”

The Gobi: there are not many detailed map sets available for Mongolia, and most first-time visitors go with local guides (and if you hope to communicate with local people, you will definitely need a translator — unlike in the Sahara where there is a colonial history and you can usually find someone who speaks French or English, Mongolians in the more remote areas do not usually speak a second language). However, it is possible to navigate with existing maps and GPS as long as you have researched the routes well. Mapped “roads” are historical routes that have been in use for centuries, but expect to have to adapt to changes on the ground (again, having a translator will be helpful), as seasonal rains can cause permanent alterations. In Mongolia the pistes usually go straight for very long distances and the most used tracks tend to all go the same way, with deviations only to avoid washboarding. It is important to note, if you are in an area that is not heavily travelled, that it is possible to find the “most used” tracks go “nowhere” — this can happen because Mongolian nomadic herders are actually “semi-nomadic” and have “summer” and “winter” pastures, where they go each year and set up a camp compound that stays in place for the time they are in that area. In remote areas the tracks to and from the compound will be the “most used” tracks, but if the family has recently left for the season, the tracks will end in empty desert. Passes around and over mountains (and sand dunes) are well-known locally and anyone you encounter while travelling in a region will be familiar with them and may even offer to guide you safely to the next waypoint rather than give you directions.

[All text and photos copyright JoMarie Fecci/USnomads unless otherwise noted]